The first jump was absolute luxury. We budding paratroopers had been fed a splendid breakfast of cereal, followed by bacon and eggs served by gorgeous WAAFs in the mess hall at Ringway airport. Afterwards we had been transported to Tatton Park in a comfortable 34-seater coach, rather than being bumped and jostled in the back of a smelly Army lorry. This was the life and we all agreed that the RAF certainly knew how to treat such fine fellows as we. Now we stood in the early morning mist, stamping our frozen feet on the crisp frosty grass, as we were each given a parachute from the back of one of the afore-mentioned smelly army lorries. We studiously tried to ignore the ‘blood wagon' (ambulance) indiscreetly positioned alongside.

With great satisfaction I noted that my ‘chute was clean, firmly packed, and with nice square edges. Not so in the case of the soldier given the last ‘chute to be handed down from the lorry. It was AWFUL and looked like a bundle of Chinese laundry which had been savaged by a fierce dog. Rigging lines festooned from each corner of the pack; folds of silk protruded at random; canvas webbing showed in places where webbing should not have been, and strange lumps were in evidence throughout the pack. The miserable recipient carried this misshapen bundle between us, asking each of us what we thought of his chances of surviving a descent using this untidy package. He got little sympathy from us as we were only too glad somebody else had this ‘chute, rather than ourselves.

Getting more and more dejected he approached our sergeant to ask his views on his prospects for survival. With a casual glance the sergeant told him “it will probably work o.k”. It was the use of the word ‘probably' that was the final straw. With a red face he slammed the offending bundle to the ground and loudly declared that no power on earth would get him to jump using that abomination parading as a parachute. Of course, he was given a beautifully packed ‘chute when the next delivery was made a few minutes later. The broad grin on his face told us of his satisfaction. Somebody had miraculously produced a football and an impromptu game of 25-a-side started as we tried, unsuccessfully to avoid watching Bessy (all our balloons were called Bessy) rising to the skies, discharging another soldier from the cage beneath her belly. Then it was our turn…..

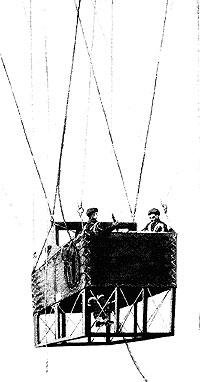

We stood beside the winch as it noisily drew Bessy to the ground and we clambered onto the cage's small platform as it swayed and bounced beneath the huge silver mass of Bessy overhead. I was first to board and stood at the back of the cage. This meant that as No.5 jumper I would be the last to descend. The RAF sergeant parachute dispatcher in the cage called out “Eight up. five down” (Eight hundred feet of altitude. Five men dropping) and we started gently rising away from the ground with its friendly familiar environs. As we rose, more and more of the distant countryside came into view and we could see a vast patchwork of fields partly covered in snow with tiny villages showing through the mist. Looking around I noticed my fellow occupants of the cage were as white-faced as I must have been, although I doubt they could have been anywhere near as scared. With a sudden jolt that sent our cage bounding about crazily, the balloon stopped rising and the RAF sergeant called to me “No.5, check to see if there is a green light showing at the winch”. Looking over the back of the cage I saw the winch man displaying a steady green light on his Aldis lamp. I informed the sergeant who immediately told No.1 jumper to stand in the door. A second's delay as the sergeant gave his equipment a brief check then “Go” he shouted.

Mesmerised I saw No1 disappear over the side of the cage and the strap connecting his parachute to its anchor point above the door started slapping and writhing as No1's parachute was drawn from its envelope. The loss of weight by No.1's departure caused Bessy to jump about like a bucking bronco and we clung on like grim death to the rail lining the sides of our cage. On the ground an RAF officer was wheeling, of all things, a pram around the drop zone. On this pram was mounted a large amplifier and the officer was calling out instructions to No1 as he descended. We could not see this activity but could hear, and were encouraged by the voice indicating No.1 was safely down.

I think the biggest fear of all of us in the cage at that particular moment was that we would ‘jib' (refuse to jump). We had seen those who had ‘jibbed' and their undignified departure from Parachute Training School was spectacular. Within the hour they were out of camp, onto a lorry, and standing in shame-faced silence on a railway platform, each awaiting a train back to his parent unit. With mounting terror I watched as Numbers 2, 3, and 4 took their places in the door. Now it would be my turn.

“Stand in the door number 5” said the sergeant and I gingerly crept forward, clinging fiercely to the handrail lest I should tumble accidentally through the door. It was silly really as the intention was for me to leave the balloon cage anyway. However, I did not want to go out before I was fully ready. During all our training we had been conditioned to react immediately to the word “Go”, bawled at us by our instructors. As I stood in the door gazing out at the cold, hazy, distant world below the sergeant at my side quietly said ‘Go.' I could not react to such mild words. Turning to the sergeant I said “Shout it please sergeant, whereupon he bellowed in my ear “ GO “ .

The reaction was immediate and I found myself dropping at immense speed with my stomach in my mouth and a gale blowing in my face. I was aware of something tugging and wriggling on my back as the parachute was pulled out of its pack. The actual distance of the fall is, I believe, only 225 ft before the canopy develops, but to me it was an age. Strangely enough, I got the impression as the ‘chute opened that I was being drawn upwards. With a sharp crack the canopy snapped open above my head and I was swinging gently towards the earth, nothing beneath me but space and a wonderful feeling of weightlessness. The RAF officer was calling instructions from his mobile loudspeaker and he looked quite comical from my vantage point several hundred feet above him.

Without flight training, unlike our feathered friends we humans cannot judge speed of descent or determine exactly where we will land in a situation such as my present one. On the ground beneath and ahead of me there was a soldier bending over as he rolled up his previously used parachute. It was only too obvious that at my present rate of descent and in my present direction I was going to land squarely in the middle of his neck. Screaming a warning to him I saw his puzzled face as I soared over him whilst still at least 100 feet above his head. Then quite unexpectedly the ground rushed at me and with a loud “WUMPH” that must have been heard all over the drop zone I hit the ground like a sack of potatoes.

The feeling of euphoria at having overcome my fear, and of landing safely, cannot be described. At that moment I could have taken on the whole German Army single-handed. Rapidly bundling up my wonderful ‘chute I raced to join my pals who were all excitedly chattering to each other describing their common new experience as they gulped down mugs of tea kindly provided by the Church Army mobile canteen parked at one corner of the field. We had done it, the first jump was over.

Before Palestine

I had been selected for RAF aircrew and placed on their Reserve for over a year before they decided that as we were losing less and less aircrew we would not be needed, so they transferred us into the Army instead.

We were readied for an invasion of Norway just as the Germans surrendered. Then we were issued with jungle equipment and our advance party sent to India just as the Japs surrendered. Why did they always surrender just as I was ready for action? They eventually sent us to Palestine to sort out the problems there.

I don’t know if you know the history of that conflict but, briefly, the British promised Palestine to both the Jews and |Arabs. When Jewish refugees from Europe tried to swamp Palestine the Arabs strongly protested and we paras were caught in the middle. Initially we had great sympathy for the refugees but were amazed and hurt to be called ‘Gestapo’ by the very people we had fought to save through six long years of war.

We found ourselves facing two very nasty groups of dissidents. The first was a mob called the Stern Gang. The second were the IZL (Irgun Zwei Leumi). Each tried to outdo the other in killing of servicemen. It was a hard and bitter campaign and we never knew if the friendly Jew facing us was ready to shoot us given the opportunity.

I can give you three examples of the type of evil we met up with. My pal was in a Jeep travelling a quiet road when suddenly a string of what appeared to be sausages (home made mines) were pulled in front of the Jeep. The driver rapidly turned the Jeep whilst my pal brought their Bren gun from the front-mounted position to the rear to cover their retreat JUST IN TIME TO CATCH A BURST OF MACHINE GUN FIRE IN THE FACE FROM BEHIND A NEARBY BUSH. I had the unpleasant task of washing his blood and brains from the Jeep next day.

A few days later I had the same experience when a single mine was pulled in front of my Jeep. Realising this was probably another ambush I accelerated hard and straddled the mine. I immediately alerted the nearest army camp but, of course, by the time they arrived the Jews had fled. This was the type of sly fighting we had to face for three years. No pitched battle but we were just as dead no matter whether the bullet that killed us came from an old Jewish hunting gun or from a German Schmeiser.

On another occasion I was driving an army lorry down a steep winding hill from Transjordan when, as I rounded a bend, I found an extensive area of roadway smothered in heavy oil by the Jews. They would warn their own people of the hazard ahead, but the intention was to send our vehicles off the road and over the edge of the cliff. Luckily I was driving fairly slowly and managed to negotiate the hazard. I intended to cover the oil with sand but the officer I was driving suspected an ambush so we raced to a nearby army camp to get help. By the time they arrived a motor cycle military policeman was killed when he skidded on the oil.

There are many other tales to tell of this period in British Para history. Some 283 of our chaps were killed during that time so it wasn’t much fun out there, even though we had no glorious battles to commemorate. Soon we ourselves will be a memory and our stories will be forgotten, either that or we will be too ga-ga to even remember what we had for breakfast, never mind what happened all those years ago.

Colin Reynolds