Antoni Szulakowski, was born in the village of Sienkiewicze, close to the Soviet border, on 5th December 1924. Sienkiewicze is a small village in the region of Polesie where the river Prypiat snakes through old forests and marshlands. (I always imagined my father as a Polish equivalent to Huckleberry Finn; fishing, kajaking, and exploring the vast wilderness of the area). Antoni’s father, Konstanty, was a forrester (gajowy) for the government and worked in the local woodland of Sitnicki Dwor. Mother, Anna, looked after the family’s smallholding and the four children (Antoni was the eldest).

September 1939 saw Germany and the Soviet Union invade Poland on two fronts and, in accordance with the Ribbentrop-Molotov Agreement signed between the powers on 23rd August of that same year, the Polish Commonwealth was divided equally as spoils of war. The Szulakowski family, along with the rest of the inhabitants of the Eastern Borderlands, then forcibly became Soviet citizens. Interrogations, intimidation by militia, and mass deportations to the gulags of Siberia then began.

On 5th December 1939 the SNK (Soviet Commission for Internal Affairs) issued orders for Konstanty's arrest and deportation to Siberia. He, and consequently his family, were considered potential agitators, and so enemies of the state. These orders were executed by the NKVD (Soviet Secret Police) on the night of the 10th February 1940. Over the next year and a half an estimated 1.7 million former Polish citizens of these Borderlands were deported as slave labour by the Stalinist regime.

The Szulakowski’s spent the next 20 months in 'Sosnovaja' gulag, close to the town of Totma on the Arctic tundra, where they were put to logging. Living conditions were basic, food limited and the weather bitterly cold for much of the year, which led to a high mortality rate from starvation, exposure and disease. The family’s release was only secured when Germany invaded the USSR and Stalin turned to the Allies for help. The Polish government, then exiled in London, demanded that their deported citizens be released. Stalin thus granted an amnesty, and the release papers for my father’s family were issued on 3rd September 1941.

Hearing that a Polish army was being formed under General Anders at Yangi-Yaul near Tashkent in Uzbekistan, Antoni and his family travelled across the USSR (by train and on foot) to join their country’s armed forces. Anders army, the 2nd Corps (the 1st Corps having been evacuated to Scotland after the capitulation of France) were moved to Iran at the end of 1942. My father enlisted there on 30th August, aged 17, and was immediately posted to the 6th Rifle Company, 16th Infantry Regiment. Several months of intense military training followed with Antoni serving in Iran, Iraq and Palestine.

In April 1943 Antoni volunteered for the 1st Independent Polish Parachute Brigade, or Pierwsza Samodzielna Brygada Spadochronowa (hereafter referred to as 1SBS) which was then being trained in Fife by Major-General Stanislaw Sosabowski.

On 5th May Antoni boarded the ‘Ile de France’ at Port Said along with 1,439 other Polish soldiers bound for Scotland, and their journey proved an eventful one. The troopship followed the African coast to dock at Durban and then again at Freetown in Sierra Leone. On leaving this port, however, the 'Il de France' picked up by a German wolfpack, which chased her out into the Atlantic. The ship then had no choice but to set course for Brazil and to resupply itself at Rio de Janiero. During the two days of mooring in port, my father said that Rio seemed quite magical to him (the colours, the people, the plants) because it so contrasted with his recent experiences of Siberia. The ‘Il de France' then recrossed the Atlantic to Freetown, plotted her course north to Scotland, and docked safely in Glasgow on 21st June.

On the 3rd July Antoni was officially assigned to the 1SBS, 4th Company, 2nd Battalion. This gives some indication that my father was in pretty good physical condition, since not all of the former deportees passed the medical examinations set by Sosabowski for his men. The Polish General pushed his troops very hard, and so could not afford to take anyone that might fail his strict regime of training: his was a crack force of the highest standards.

The Polish Brigade wore standard British paratrooper uniforms, including the rimless helmets onto which the Poles stencilled their own eagle insignia in yellow. On their lapels they wore dove-grey triangular patches outlined in yellow trim with silver parachutes. The 1SBS beret was grey - in contrast to the maroon colour of the 1st British Airborne.

Sosabowski’s men were stationed in Leven at Largo House (a stately home requisitioned by the army). An assault course nicknamed the 'Monkey Grove' (Malpy Gaj) was set up here and static jumps were practised from a purposely built tower (the initial patent for this structure had already been tested in Poland during the 1930s). Under Polish supervision other Allied troops also received training, such as the French Free Forces.

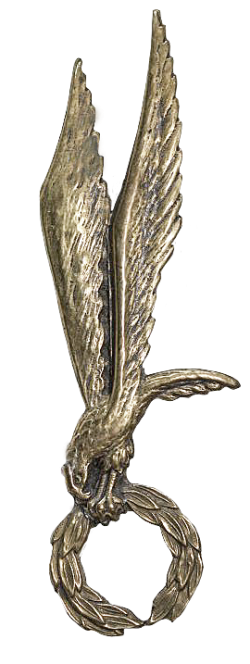

Each paratrooper had to attend a four week training course at Ringway Aerodrome (now Manchester Airport) which involved completing three aircraft jumps. On 30th October 1943 my father passed his course and was awarded the Paratrooper's Ordinary Badge (Zwykly Znak Spadochronowy). The Badge depicts a stylised eagle diving for its prey with the words ‘For You My Country’ (Tobie Ojczyzno) engraved on the reverse. Antoni's badge is stamped with the issue number, 3857. On the 7th of April, my father transferred to the Anti-Tank Airlanding Battery, or Dywizjon Artylerii Przeciwpancernej (hereafter referred to as ‘P-panc’).

My father loved Scotland, and this is why Sunday mornings in our household often involved blasting out ‘Scotch on the Rocks’ on the gramaphone player. It was in Fife, also, that Antoni fell in love with the military lifestyle. His days with the Brigade proved to be some of his happiest, which was the reason for his adamant attendance of every reunion of the Polish Airborne Association (Zwiazek Polskich Spadochroniarzy) until his death.

Along with military training, the Poles were encouraged to take courses of a more practical nature, which were designed to give each man a trade for his final return to civilian life. Antoni completed an evening course in the spring of 1944 about arable farming, and the use and maintenance of Ford tractors. His course mark was 'Very Good' (Bardzo Dobrze).

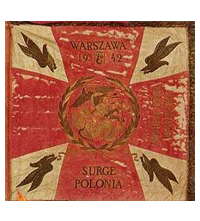

In July of this same year, the 1SBS moved to the Stamford-Peterborough area where their training intensified in preparation for Operation Tempest. Tempest was staged by the Polish Home Army, or Armia Krajowa, and culminated in the Warsaw Uprising that began on the 1st August 1944. The Brigade had been formed to parachute into the Capital to assist the AK, and for this reason was ‘independent’ of Allied orders, answering only to the Polish Government-in-Exile. As history would have it, the 1SBS never took part in the uprising, being used instead to support 1st British Airborne at Arnhem.

Antoni was stationed with the P-panc at the Georgian-style Blatherwycke Hall, where all of the Battery’s training in the use and maintenance of 6-pounder guns took place. The Hall stood near an artificial lake into which the stream of Willow Brook ran down from the village and under a sand-coloured stone bridge. The grounds had a walled garden and the medieval church of Holy Trinity stood nearby. It was an idyllic slice of England and my father loved it. The Poles also had one-up-manship on other Allied troops in the area: they discovered a stash of wine and port bottles in a tunnel that led from the Hall directly under the church. Apparently the British never did work out how the Poles could merrily get drunk without leaving the compound.

Jumps were practiced over RAF Wittering, with take-offs from Spanhoe which had the longest runway in the area at 3000ft. The Dakotas were flown by the 315th US Transport Carrier group. My father favoured glider training, however, because he liked the peacefulness in contrast to the noise and bumpiness of a C-47.

Although the majority of the P-panc landed in the Arnhem area by Horsa, on the 18th and 19th of September, Antoni went into action on Thursday 21st. Dakota no.99 dropped its stick of paratroopers just after 5pm over Driel on the southern side of the Lower Rhine (DZ ‘K’). That day, the Poles had been on standby three times before the go-ahead was given for their take-offs from Spanhoe and Saltby. Due to bad weather, the 1SBS were 3 days behind schedule and, even on the 21st, half of the Brigade were called back to England because of the weather conditions over the Channel and Belgium. This meant that, once on Dutch soil, Major-General Sosabowski belatedly discovered that half of the 3rd Battalion, and all of the 1st, were still in Britain.

My father was 19 years old in September 1944. A friend of mine once asked him if he was scared to go into battle. “No”, replied Antoni, “because I had nothing to lose. I wasn’t married, I was in exile, and the friends that were closest to me were going into battle as well. I was proud to be fighting with the Brigade, and I was proud to be fighting for my country”. I remember listening to him then, I must have been about 12 years old, and I was bursting with pride that my father had been a hero of Arnhem. Only later did he confide in me that, actually, he had been terrified on that Thursday.

When it came to the drop, Antoni said that it all happened too quickly for him to really grasp what was going on. In spite of the noise of the aircraft and the German guns, he was aware of how loud and how fast his heart was beating. The wind pressed hard against his face until his chute opened. As he looked down, passed his legs and kitbag (attached to his ankle) he could see the tracer bullets of enemy fire, which alerted him to the fact that the Poles had been dropped onto German positions. His thoughts went from “Please, chute open”, to “Please, let me land safely”, to “Please, let me find cover”. My father said that some of his colleagues prayed during their descent, but Antoni’s head was just full of what needed to be done and his priority was to find a supply canister with a British 68P radio set. (This set was carried as a heavy back-pack, and only used for short-range communication up to 10 miles).

My father had been trained as a signalman (Lacznosciowiec) for the P-panc and had therefore flown into Arnhem with the Anti-tank Airlanding Battery Command:

- Commanding Officer Captain Jan Kanty Wardzala

- Second in Command Lieutenant Tadeusz Lang

- Commanding Medical Officer Lance Seargent Pawel Arcabowicz

- Commanding Signals Officer Lance Seargent Józef Dziudzik.

After landing, whilst others were abandoning their chutes, Antoni tried to gather his together. Even he couldn’t tell me why, but he took his parachute with him all the same. Soon after, he retrieved a 68P radio, and then it was time to regroup whoever had arrived from the Brigade.

Antoni crossed the Lower Rhine on the night of the 23rd to fight within the Oosterbeek Perimeter – this was the third night that the 1SBS spent trying to get reinforcements to the 1st British Airborne:

- 21st - The Poles had been promised a ferry, but the Driel ferryman had let his boat drift (his thinking ran along the lines that this would impair German movement in the area). Instead, his gesture scuttled Polish hopes of crossing on the night of their arrival.

- 22nd - The 8th Company of the 3rd Battalion transported across 56 paratroopers. They were led by Lieutenant Albert Smaczny and joined the unit fighting under Brigadier Hicks.

- 23rd - Between midnight and 7am, Sosabowski sent over more men from the 3rd Battalion, part of the HQ, Signals Command, and the P-panc. This numbered about 250 men.

My father told me how bad it was for those crossing. A rope had been thrown over the river so that the men could pull their dingys along, because there was a lack of oars – the Poles even resorted to using spades as paddles. The rubber boats could not stand up to the constant firing of the Germans, whose position on the Westerbouwing Heights (overlooking the Poles dug-in around Driel on the plain) gave them supremacy over the battlefield. As soon as a German flair went up, all men in the boats and on the riverbank became easy targets for the Nazi guns.

Antoni waited for a transport under these conditions on the south bank of the Lower Rhine. As each empty dingy was brought to the river, soldiers climbed in and prayed for a safe crossing. When my father’s turn came to board, the Commanding Office told him to wait for the next boat – Antoni’s radio made him a cumbersome passenger. As the dingy began to pull away from the bank, it was hit by a mortar and its occupants were killed outright. For my father, that moment became his closest brush with death: their for the grace of God… He used to tell me this story and shake his head, partly in horror and partly in disbelief.

By the 25th September, the order was given for an Allied evacuation: Operation Market-Garden had failed. The Polish Brigade, still holding a defensive position at Driel, were a key element in this withdrawal of men southward across the river. Soldiers escaped by boat, although some decided to risk swimming across and had to fight hard against the strong current. It was a tortuous withdrawal under German fire, but one of the last remaining fighting units within the Oosterbeek Perimeter was the P-panc. Those who could cover the withdrawal of their colleagues, stood by their 6-pounder guns in the vicinity of the parish church. My father’s luck held out that night and he was able to escape unharmed and by boat. With him, he still carried his radio. (The P-panc suffered the greatest proportional loss of men from any Polish unit involved in the battle: 37 percent of the Battery were dead or missing, a further 22 percent were wounded and Captain Jerzy Wardzala was taken PoW).

The 1SBS were then moved back to Nijmegan and ordered to guard airfields and bridges (such as one near to Heuman) until the Allied troop withdrawal could be completed. At the beginning of October, the Brigade was finally evacuated from Holland to Belgium, and then sailed for Britain on the 11th and 12th of that same month.

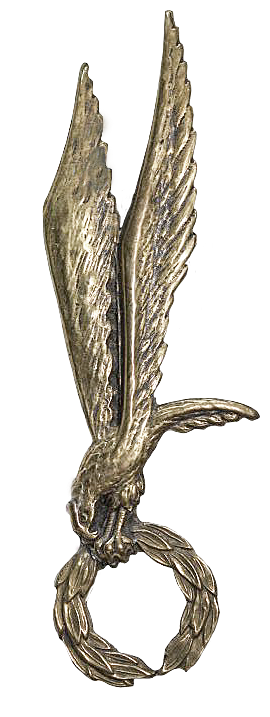

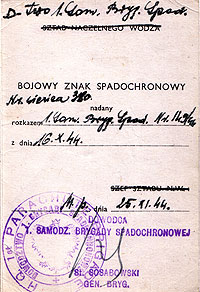

On October 16th, Antoni received the Field Parachute Badge (Bojowy Znak Spadochronowy) which was a standard issue award for all Polish paratroopers that saw action during WWII. His issue number was 380. Furthermore, my father was seconded to the Anti-Tank Non-Commissioned Officers’ School (Szkola Podoficerska - Specjalnosc P-panc) and promoted to Lance Corporal on December 19th.

Yet Market-Garden turned out to be an unbearable tragedy for the Brigade. On the 9th December, Major-General Sosabowski was dismissed: a humiliating order that came straight from British High Command. Both General ‘Boy’ Browning and General Montgomery used the Polish Commander as a scape-goat for the failure of their planned operation. In protest, two of the 1SBS units went on hunger strike over Christmas, but this action was to be of no avail. Furthermore, British command of the Brigade was never relinquished as originally agreed before action, and this made a mockery of the 1SBS as an ‘independent’ fighting unit. This also put an end to any dreams its men might have still harboured of going into Poland to fight for her freedom.

It may seem strange, but on VE-Day 1945 my father sat in his military barracks in Germany, where he was stationed with the Allied Army of Occupation, and he cried bitterly. Germany had been defeated. However, Rooservelt and Churchill had allowed Stalin to install a puppet Communist government in Warsaw. At the same time, Poland’s so-called Allies retracted their support of the rightful and democratic Government-in-Exile. Gomulka’s regime then went on to denounce the Polish Free Forces in the West as traitors to the Motherland, because of their continued loyalty to the London government. Those soldiers who returned to their country faced suspicion, interrogation, imprisonment or deportation to Siberia. For Antoni, the greatest tragedy of all was that the Allies had ceded the Eastern Borderlands outright to Stalin, which meant that he would never return to his beloved Polesie. So complete, in fact, was Poland’s betrayal by her Allies, that the British government bowed to pressure from Stalin to omit the Polish Free Forces from the Victory Parade in London held on 8th June 1946. My father would rage about Poland's fate and, tightening his fists, would firmly tell me "This was no victory for us!"

Antoni Szulakowski relinquished his commission with the 1SBS and was Honourably Discharged on 7th September 1948. Whilst stationed in Germany, he was promoted a second time, and so left the army as a Corporal.

He chose to stay in Britain and joined the Polish Resetttlement Corps, which helped him to adjust to life in England. He soon found work, and then married my mother, Matylda Brodalka, on 7th July 1949 in the Catholic Church of St. Mary’s in Derby. They had met at the refugee camp of Ludford Magna in Lincolnshire – one of many sites run by the National Assistance Board to deal with the unexpected post-WWII Polish community.

Copyright Halina Szulakowska, Antoni's daughter