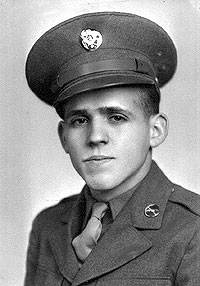

I am Walter L. Arnold. I was born in Garrard County, KY in a little village called Bryantsville. I was born on May 25, 1922. I served with the 83rd Infantry Division, the 329th Infantry Regiment, Anti-Tank Company from Camp Atterbury, IN across the Elbe River to within 25 - 40 miles of Berlin. I was a sergeant. My army serial number is 35664513. I entered the army in 1942. I was mustered out in 1945 in November. We were trained in Camp Atterbury, IN for 8 months, then went to the TN maneuvers, and there we maneuvered against the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions. We went from there to Camp Breckinridge, KY and trained until April the next year. Then we trained for four months in Wales, England. We landed after crossing the Atlantic Ocean with the largest convoy to ever cross. We arrived in Liverpool, England. I was in charge of a ten-man squad. We had a 57-mm anti-tank gun and a 50-caliber machine gun mounted on a three-quarter ton truck.

Today I will be talking mostly about our stay in Normandy and the Battle of the Bulge. We were being rushed from England to France. This was a priority trip. We were needed badly. The beachheads had been won; the troops now in France needed assistance. The weather was so bad that we spent several days in the English Channel, waiting, cleaning our weapons, and making sure they were in working order. When the storm struck, the 83rd Division was still lying in the ships just off the beach during the entire storm. This was an extremely uncomfortable and trying experience. This happened on June 19th.

When we arrived we could see that the waters were congested with waves of troops from many directions. As far as we could see ships going and coming carrying supplies to the beachhead and carrying the wounded back to England. We could see all kinds of blimps to keep the enemy planes from coming in too close. Before our eyes, we could see the cliffs of France, and I wondered many times, Why? Why would anyone try to land here, with all the pillboxes and machine guns and the big guns looking down upon the English Channel? What a price was paid in the lives of American boys lost and wounded! There were all kinds of poles, like we know as telephone poles, to keep our gliders from making a perfect landing. There was destruction in every direction.

I shall never forget the first day we set foot on French soil. We were told to dig in. I was scared, man was I scared! They had warned us about the enemy mines and land mines. Every time I hit a rock, I thought it was a mine. One man about 6'4'' said, "I'm not going to dig in, I'm not afraid of the German soldiers."It wasn't long after that until the enemy laid down an artillery barrage on our position and I tried to get into my fox hole, but to my surprise, all I could see was two, size-14 shoes sticking out of my fox-hole. That man did not have any trouble digging in after that.

We moved inland about seven miles and relieved the 101st airborne division, the division we had maneuvered against in TN. Now, we were no longer training. The fact was, we were face to face with the enemy. One trying to kill you at every move. We were being shelled with artillery and mortars, air attack and the burp gun and they were all exploding all around us. I lost my best friend here. He was Russel Mengle. We found ourselves in the hedgerows, where we were stuck for six, solid weeks. There was death everywhere. Cows and horses, German men and American men.

After sometime the medics came up with their jeeps and trailers. With the red cross written across their helmets and across their chest and across their vehicles, to pick up the dead Americans and Germans and put them in the same trailer, one on top of the other to take them back for burial. Nature looked down upon the scene that day. Birds were singing in the treetops, the sun was shining, the soil had been enriched by the blood of man and beast, but nature just didn't seem to care.

The days in the hedgerows we had mostly ten-in-one rations. Somedays our cooks from company headquarters would try to get us a hot meal. You would try to get behind a knocked-out tank or protection behind a hedgerow. There would be smell of death all around you. Sometimes you just didn't want to eat. Nothing was inviting. While in the hedgerows, the Germans were so good with their artillery, that one shell would fall on one side of your fox-hole and role you over south, and another would fall on the other side and roll you back North. It was a living hell. We would have to dig under the side of our foxhole because the Germans learned to make the shells explode up over our foxhole.

After six weeks of this, we finally broke out. Now is the time for our first shower and clean clothing in weeks. We all as a company took off our clothing, waited our turn for a cold shower (and I mean a cold shower!). Not many wasted much time under that shower. This was a make-shift shower, with a truck, and a water tank and a pump. After we had had our great showers, as cold as they were, we moved south in France, where we left behind some of the bravest men one could ever know. They were our heroes. The 83rd was given the mission, of clearing the enemy, 15,000 in number, from the St. Malo peninsula. Taking the town of Dolet, and then on to Chateauneuf. We were now faced with a German stronghold called the Citadel. An effort was made to get Colonel Van Aulock to surrender, but he refused.

After our troops had failed to take the citadel, on August 11th, plans were made to attack first with bombers, artillery and all kinds of ammunition. We set up our 57-mm gun and our lieutenant ordered just before the attack, that all guns from every direction would fire on the citadel for the length of ten minutes. I was to keep time. Just before the ten minutes were up, I called a cease-fire. Just as our men moved away from the gun, the Germans laid an 88-mm artillery shell beside our gun, and luckily I had made the men move out just before that time. On August 17th, someone saw a white flag. The Colonel surrendered along with 595 men. The rumor I heard was someone hit the air system and stopped the flow of fresh air. I do not know if this is true or not (for photos of the citadel at St. Malo, see the Photo Gallery, 1999).

Moving south to the city of Angers, then on to Orleans. It was in the Loire Valley on September 16 and 17th, General Botho Elster surrendered with all 20,000 soldiers to General Macon, our division commander.

While in the Loire Valley, the cooks from our company headquarters sent out a box about 14 inches square with white stuff in it. I went into the farmers garden and got some fresh potatoes right out of the ground, and peeled them, cut them up and was going to fry them. I put some of that white stuff on them thinking it was lard. I had one of the stickiest, messes you ever saw. I threw it away, without even tasting it. Sometime later, I asked the cook what it was. He said that it was white honey.

After clearing out the Loire River Valley, we then made our way 300 miles into Luxembourg. We were around the Moselle and Sauer Rivers. While we were in Luxembourg, we saw several of the buzz bombs. One day as one was going over, I jumped to my 50-caliber machine gun. I was going to try to shoot it down. One of my men said, "Are you crazy? Don't shoot that thing down here. Let it travel on and fall somewhere else."

Some time in October of 1944, we went to the vicinity of Hellange for training against the Maginot Line, and preparing for the Siegfried Line. I have a picture of Sg. Fuhrman and myself standing in the center of the Siegfried Line.

While we were still in Luxembourg (I wish I could remember the town that we were in, but I do not), we set up two 57-mm Anti-Tank guns. I went in and took a room in the house of these people. They were good people. Their parents and girls would come to our room at night and we would play games. I had a lot of fun, and they had a dice game that we tried to play. I would take those dice, and just scoot them across the table, and they would say, "No, No, No." And they would make me play in the right way.

We had some good times, but they would play with us until a certain time. It was their bedtime. And then they would go to bed. It was here that I took a 57-mm shell and worked the big bullet out of it that weighed 6 pounds, burned the powder after pouring it on the ground, and set the casing of that 57-mm down in the ground, and took a hammer and hit the cap that made the thing fire. When I hit it, it jumped about eight feet in the air, and I gave it to the people to keep as a souvenir to remember the Americans that were there.

Then while I was still in Luxembourg, they wanted to move our squads around. There was one squad, Anti-Tank gun, upon a great big hill, where it was visible and not many people wanted to go there. But finally, our time came to go up and set an outpost. We made our way up there under artillery fire. While there, I found all kinds of canned fruit. I opened that canned fruit and I was the cook for my squad at that time and I made all kinds of fruit pies and we ate like a king. One day, we looked out in the barn and spotted a great big old sow, a hog. I said to one of my squad members, Chaney, "If you will heat some water, we will kill that hog and we'll have some fresh meat."

We did. I salted the meat down in the back of my 3-quarter ton truck, that pulled the 57-mm gun. I should not have done that. I regretted that because I felt that it was wrong that I took that man's hog. And it makes me remember when we were still in the hedgerows, some man, I do not remember the company, killed a farmer's beef. They were passing it out to different men in other companies. I would not take any of it, because I thought it was wrong to kill the farmers beef. I understand that the Frenchmen would be repaid by our government when something like that happened. I'm not sure. I wish we had not done that.

One day I asked for a jeep and a driver so I could go visit Andrew. He was with the 95th Division. He had been wounded and had been sent to a hospital. I was writing to him once in a while. It was my understanding that he was back with his company. When I got there he was not back. I was real disappointed. When I think back over it, it was a wonder I ever found his division. I guess I had learned to read a map real well.

The 1st of December, the 4th Infantry Division relieved us in Luxembourg, and we went into the Hurtgen Forest, where they had been fighting for so long and were beaten so bad, that they were seeing German soldiers that were not there. There in the Hurtgen Forest we pushed our way through without too much problems. We noticed German planes and American planes were in several dogfights. The Germans seemed to be plentiful with their planes at this time. Really we did not know what all of it meant. We soon received word from our company headquarters that we would have to retreat because the Germans were pushing in behind us. We could not go back the way we had entered.

The German had cut off our path of departure. We made it back to our company headquarters about 10 p.m. that night. We had traveled about 60 miles from Duren to the vicinity of Rochefort to hit the Bulge and the Germans at the top. When I arrived back to my company headquarters, my parents had sent me a fruitcake. I divided it with my men. The cook had hot coffee for us. That was the best cup of coffee I had ever had before or since. My mother had written the news of my grandmother's death, and she had sent me some more goodies. I did not receive them. I learned later about my grandmother's death. The Germans, I am sure, had some good cookies for once. I learned about my grandmother's death some time later on from a girlfriend, back home.

We were now facing the best troops the Germans had, Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt. He was hoping to destroy the allied armies, and drive us back to the English Channel. There were paratroops, their best tanks, from the 6th Panzer Army, they sent crack SS troops out to do this job. It was here that our Lieutenant took Ralph Palmer from my squad to make him a gunner, to give his corporal strips, to work his way back up to Sergeant where he was when he lost his stripes early in France.

The very next day, he was hit and lost both legs above the knees. That same night, I lost Chaney. He was hit and I never heard from him again. He was a gambler. He had not sent all the money home because of his rank. I had about at this time, $300 that I had sent to the P.O. to get a money order that belonged to him. I sent it to his girlfriend in West Virginia. I guess she got it. I really never did know.

The next morning, we were moving out somewhere near Rochefort, Belgium. The Germans laid down one of the hellish artillery barrages. John Balistere was hit in the thigh, and the metal went all the way through the bone and his leg was up under his stomach. He was screaming for help. I had to roll him over. On my right, Midday Delfonte was hit through the steal helmet head and all and he died within two minutes. When this shelling was going on, I felt the Lord push me to the ground. I heard the shelling coming. It started a few yards up the road and was making its way along the road to where we were. When the Lord pushed me to the ground, lying there I was not that afraid. I was looking up. I could see the shells exploding all around us, the tree tops were falling, etc.[8]

After I did all I could for these men, I sent one of my men down on the road, to get help. Help was not too far away. I then took Delfonte's gun, stuck it into the ground and put his helmet on it so people coming looking for the dead could see where he was.

It was cold and the snow was deep. We moved into a village one night and I was so tired that I took shelter in a building. We posted our guard and I went to sleep. During the night, the Germans hit a building across the street and burned it down. I did not know it until the next morning.

We did have a good meal on Christmas Day, 1944. That day the weather cleared and the skies were clear, and it was a picture to look up and see all the American airplanes, the B-17, and all kinds, and you could see all the vapor across the sky, it seemed to say to the men on the ground "Merry Christmas, and a Happy New Year."

During the Bulge, I went with a hardened soldier to clear out a basement where I knew there was a German soldier. I called to the German and asked him to come out with his hands up and he was a little slow in responding. The soldier with me reached for his hand grenade, and started to pull the pin, and I had to order him to hold on to give the man a chance to come out.

After I got the German out of the house and reported back to our officer, we searched and interrogated him, he told of a young wounded German soldier in a house about one mile over a snow covered hill. So here I go, taking the German soldier with me. I told him in German to run. This way we were not an easy target. When we arrived, I made the German soldier open the door and enter first. As I entered the house, I saw a young German soldier lying on a couch. At that time the kitchen door opened, I was ready to shoot my sub-thompson machine gun, when I saw that it was two Belgium women walking in. My heart jumped in my mouth. How glad I am that I did not let the soldier who wanted to pull the pin on the hand grenade in the other house go first. He would have started shooting first, then think and ask questions.

During the Bulge, I saw or heard men pray that had never prayed before. I saw men trying to bury their faces in the soil for protection. We heard all kinds of rumors, most of them turned out to be true. We heard that the Germans were dressed in American uniforms, that they were penetrating our lines, trying to get to and assassinate General Eisenhower. We also heard about the German tank division that some of our men surrendered to, how they took them out into an open field and shot them like animals in cold blood.[9] We heard all of this, for your see, news travels fast in the war.

At last the Battle of the Bulge came to a close. The 83rd, 329th Infantry Regiment played an important part in the Battle of the Ardennes, as well as in Normandy. We stopped the Germans from advancing any further out of Rochefort. We lost a Lieutenant Sherwood Roe one day. There had been some rain, and he put on a German raincoat. And men from another company entered the house where he was. Thinking that he was a German soldier, they shot him without asking any questions, dead on the spot.

Around January 22, after the Battle of the Bulge, the 329th received over 500 replacements to bring us back to strength. Now the 83rd was relieved. This was the first time since June we were out of contact with the enemy.

After our time of rest and regrouping, the 83rd pushed towards the Rhine River. We were moving towards Neuss, and we reached the Rhine across from Dusseldorf; the first infantry division to reach the Rhine in strength. That night at 10:00 pm we were told that we were going to make an attempt to move across the bridge that was still standing across the river. Some time after that, the enemy blew the bridge, and I want to tell you what relief.

I did not want to get out on top of that bridge, and let them blow it out from under me. We crossed the river on a pontoon bridge on our way to the Elbe. On March 29th, 1945, the Germans were almost defeated everywhere we went with just small resistance. The 83rd was moving so fast, that it was named the Rag-Tag Circus by a war correspondent. Men were riding on jeeps and tanks and trailers and German trucks and ambulances and motorcycles, and command cars and anything that they could find that would run. Our division made history writing a new chapter in infantry history as we raced our way across Germany, making one final blow at Hitler and his company.

I shall never forget the day we reached the Elbe River. We had traveled 265 kilometers in 10 days; almost unheard of. The enemy had withdrawn to the east bank of the Elbe River. It was here that a German plane came in low over the water. I am sure to see where we were and how fast we were advancing. To my left I heard a 50-caliber machinegun open up, firing at that plane. I looked and I could see the plane coming towards me.

Our regimental commander, Colonel Crabill was standing near the river in front of my 50-caliber machinegun. I jumped on the truck, pulled back the bolt, thought I had it ready to fire and to shot at the plane. But it just would not fire. I guess it was a good thing. Because Colonel Crabill was in the line of fire, and I would have to shoot over his head, and I had no guarantee that that would happen. When I checked the gun to see what was wrong with it, I found that when it had been cleaned and put back together, the barrel had not been screwed all the way back in place. Then you were supposed to back it off nine clicks, and it was supposed to fire.

We moved on across the river that afternoon, with a boat that had some treads across it, a couple of boats with a motor that could take our 3-quarter ton truck across the river. We moved into a town, name Walternienburg (click here for map of town and events of this day). The Lieutenant said to me, "Set up your gun on that corner of the street, and we'll move out there and dig in under cover of darkness." As we moved up, a German tank shot from about 1000 yards, the first round was an armored piercing. It hit about three feet above my head into the wall where I was standing. I thought I could run.

But I was the last man into the house. The next shell was a high explosive. It hit my truck and gun, and burned them up. I had all kinds of souvenirs, money, pictures, I even had a rifle with a telescope sight on it. I lost it all. But thank God I was spared that day. That afternoon, my lieutenant came to me with a German bazooka, and we slipped around some buildings to where we could get to the side of that building. That tank that had been shooting at me had moved in to within 300 yards of that building in that little town. We were going to destroy that tank. But the bazooka needed a fuse that we did not know at the time you needed to have. And it would not fire. We learned all that a little bit later.

We had another 57-mm gun set up, and our men were firing on that tank. And I believe that we must have hit the turret, so that it could not level its gun, because they could have lowered their gun and knocked our gun out and destroyed some of our men. But they were shooting over our heads all the time.

The same day, a German soldier got lost, I'm sure. He came riding up the street on a motorcycle, with men from our division shooting at him. And he jumped off by the building I was in, and one of my men that was on guard shot and killed him as he was trying to enter the room where I was.

After all this, we men became hardened at the sight of death. We were shocked to see the American men die at the hands of the Germans. Some would become so hardened that at times they would have no feeling at all for the enemy. I saw a Lieutenant take out his .45 and shoot an already dead German 3 times.

Here we met the Russians. And I shall never forget the first Russian plane flying over head. It was surely a welcome sight. The war was officially over on May 9th, 1945, when the Russians took our place on the East Side of the Elbe River. That day was V-E Day. We did not know what we were going to do. So we went on more training with live ammunition. We thought perhaps we were going to the Pacific. But thank God we never did have to make that trip.

I want to relate one more story. It's not a pleasant one, but it happened on our journey across Germany. We were making our way, and our troops had made their way around a German pillbox, and there were several German soldiers still in that pillbox. So we moved up to were we could set up our guns so we could see it, and there was a big church steeple there. I wanted to go up in that Church steeple and see from an observation tower what I could see down on that pillbox. So I made my way up and the Germans saw me going in.

I peeked around the corner of that window, and just as I did a German took a thirty-thirty riffle, and shot within an inch of my head. And I'm here to tell you, I left that observation tower and went out of there. It wasn't long after that, the Germans threw up a white flag. We called a truce for one hour. Went over and talked to them. Asked them to surrender, but they would not. Just one minute before the truce was over, John Ryan was up in that tower with a Browning Automatic Rifle, and he shot and killed three German soldiers needlessly. The next morning, Colonel Crabill ordered us to break that box open. It was concrete and steel, 6-foot thick. We set up three guns; two 57-mm and a 76.

We pounded and we pounded and we pounded, hitting the same spot with armored piercing 5 shots, and one explosive a 6-shot. After I had fired 100 rounds with my 57-mm Anti-Tank gun, we finally broke through. The Germans threw up a flag and threw up their hands, and running out they cried for mercy. So we did not kill any more of the Germans there in that pillbox. I had some beautiful pictures of that pillbox that I was going to bring home, but when the Germans knocked out my equipment, they destroyed the pictures that I had.

After we broke open the pillbox, I had shot over 100 rounds of ammunition in that 57-mm gun and it just burned it up. What I mean by that, the rifles inside of that barrel, that makes that shell twist when it comes out, and makes it more accurate when you shoot, it burned those riffles out. So I had to turn it in, it wasn't any good, it wouldn't be accurate. I had to get a new one. So when I did that, I divided my men in two more squads with other men. I went back to company headquarters to wait for a new gun.

While I was in company headquarters, I became so bored and so restless that I caught the first truck, I don't remember whether it was a mail truck or a cook truck, going to the front lines, and I got on that thing and I went with them. Before I got back to where my men were, the Germans threw down a big barrage of artillery fire, and we all had to stop and jump out and run in a ditch. And here I found myself back again in harms way, just because I was restless and bored, and just because I wanted to be with the men I had traveled so many miles with. Yet when you think about it, it was a stupid move. I could have stayed back there for several more days, and not worried about being hurt or harmed, but I just wanted to be with my men.

I never thought once about giving up and becoming a prisoner of war. I never discussed the possibility with my men. When the war was over, two of the soldiers pulled out a white flag. They said they would have used them if needed. I said to them, "If you had, I would have shot you." I doubt if I would have.

We went across the northern parts of Germany, fighting our battles. But coming back we went through the southern part. We were making our way to Reims, France, where we were supposed to take a ship to come back home. Would you believe it, the longshoremen in New York City went on a strike, and I stayed in Reims France for 30 days for no reason at all. We not only made our way through the south, we also went into Czechoslovakia for just a little while.

And then we made our way back. It was a seven-day trip back from Le Haure, France. We came on a little German transport that we had captured called U.S.S. Lejeune. We were making our way into New York Harbor, a small ship came out with a big band on it, and young girls singing, Welcome Home, Boys, Welcome Home, Job well done. And I stood there a hardened soldier, and wept like a baby when I heard them singing. And then we went to Camp Kelmer, and we were processed and got on a troop train heading for Fort Knox, Kentucky. No place to sleep, so I stretched out on the floor under three of those seats and sleep most of that night on my way back to Fort Knox.

I was relieved there, and when I arrived back in Lexington, my father and mother welcomed me. I looked over to the side and there I saw a young man I did not know. He had grown up in the nineteen months that I was overseas. It was A. T. He and Drennan were now grown young men. Drennan was very small when I first went into the army, and I bought him a soldier suit for him to wear. I had not been home long. In fact, the very next day, I made my way to a girl I love more than anything in the world. I took her some candy, some chewing gum, and in nine months, I made that little girl my wife, the mother of Bill and Rick Arnold, our two sons. After 52 years, I'm still in love with my whole family. Thanks be unto God.

This is the way I remember the war. I have been a United Methodist minister for 47 years. I am now retired and living with my wife of 52 years in Lancaster, KY.

Walter Arnold