I made my application for a two-year enlistment in the U.S. Navy in Peoria, Illinois on October 24, 1942. The recruiter took five recruits to the Naval Reserve Station in Chicago, Illinois on November 5, 1942 where we received our physicals and were sworn in. The fine print stated that in case of war or national emergency I would be obligated to serve an additional six months after the end of a war or national emergency. I served three years and six days. We stayed in Chicago over night and boarded the North Shore train at 7:00am the following morning bound for the U.S. Naval Training Station at Great Lakes, Illinois. Boot camp lasted twelve weeks. I took a lot of tests and did real well on mathematics, mechanical drawing, and mechanical ability tests.

I applied for carpenter mates school on November 28, 1942. After completing boot camp and taking a leave, I returned to Great Lakes S2C Rate. On January 25, 1943 I entered carpenter mate school for the next sixteen weeks. We had no shop classes, only textbook work. Graduation was May 17, 1943 and I was 20th in a class of 89 with a 93.1 average. I received a Carpenter Mate 3rd Class Rate (CM3C). I heard about a school for small boat repair, applied for it, took the test and was accepted. On May 20, 1943 I was transferred to the Naval Landing Force Equipment Depot, Newton Park Ford Plant, Norfolk, Virginia.

On June 1, 1943 I started training in motor repair, machinist, shipfitter (welding), electrician and carpentry (wood boat repair). Shop work started at 7:30AM until the noon lunch break. Class work and the next day’s assignments lasted from 1:00PM until 3:00PM. We couldn’t leave the base until 5:00PM so twenty to twenty-five of us would stay in class and have a question and answer session on the class for the next day. They wouldn’t always be the same guys but maybe fifteen of us would be there every day. When you worked in the shop you would be with guys with the same rate on what you would work on.

Each training class was about three weeks. Out of about three hundred that started the class, each three-week test would wash out about half. In September they picked thirty men. We were formed into three mobile repair units; E-9-15, E-9-16 and E-9-17. Twenty-seven men received Second Class Petty Officer and three received First Class Petty Officer. They were older than the rest of us and were six-year men.

My unit, E-9-17 consisted of the following men:

- MOM1C Lesta Willis (our C.O.) Morehead City, NC

- MOM2C John Buchanon Mathesisco, VA

- MOM2C Harry Kilmer Marrleyburg, PA

- MOM2C Perry Kimble Pittfield, NH

- MM2C Andy Kochelis Plymouth, NC

- MM2C Donald Call Newport News, VA

- SF2C Robert Parker Kalamazoo, MI

- SF2C Louis Glaven (took all the pictures) Atlantic City, NJ

- EM2C Arthur Peck Nowata, OK

- CM2C Robert Shaver East Peoria, IL

We received three trucks that when grouped together made a complete shop. We had to waterproof the battery, carburetor, plugs and starter, start the truck, set the engine to 2500 RPM, put in low gear and hold the clutch down. Then the co-driver would climb out on the fender and re-pack the carburetor. I would then slowly let out the clutch and drive through five feet of water, the water coming into my lap. After driving through the water, the water proofing had to be removed from the battery and the plugs to keep from overheating. Then we setup the trucks to make a complete shop, and learned the location of all the tools and spare parts. The trucks were then shipped to destinations unknown to us.

We finished our training October 25, 1943 and were transferred to New York, NY October 27, 1943 to board the Queen Elizabeth the following day. We were about the first to go aboard. Then they started boarding approximately 22,000 soldiers. We sailed November 5, 1943. The ship traveled alone because it could out run submarines. They had divided each deck in three sections and we were in the green section. You could only leave your section to eat. The dining area had long rows of tables about two feet wide and three and a half feet high. We ate while standing and facing someone on the other side of the table, hoping they wouldn’t get seasick. Everything was like an assembly line, moving only one way.

We only had thirty minutes to eat, then slide our trays down to the end of the table. When you finished you returned to your deck in the green section. Stairs were designated either up or down. Starting on the port side all rows between bunks (4 high) went forward except the starboard side back. My bunk was on the port side welded to the outside hull. When I went to the bathroom I went forward to the end of the green section. I returned on the starboard side across the other end and back up my row. Walt Disney got his idea from the military.

One night we were in a storm around Northern Ireland. The ship rolled so much the screw would come out of the water and shake the whole ship. The ones on the bunks against the hull would travel at least thirty feet. I held my breath on the high side hoping it wouldn’t roll over. The ship docked in Glasglow, Scotland November 9, 1943. Since we were the first to board in New York, it took two days before we got off the ship. The gear was unloaded by layers from the hole. Our gear was on the bottom. Since there were only about 150 sailors on board, and since our bags were white, we had no trouble finding our bags. All of our bags were mashed about four inches thick. I had an 8x10 inch picture of Shirley in a wooded box I had made. The box and the glass were broken and the picture was destroyed. I also had a new pair of dress shoes that had been folded lengthwise and popped off the heels. The soldiers left by truck or train. We marched about a half-mile to an old stone building like a warehouse. It was very cold and inside the building was not much better.

On November 17, 1943 we boarded a train bound for Exeter, England. The train stopped in three towns in Scotland and England. We could get off the train and walk around town. I think they stopped because the sailors and soldiers could spend money. We bought mostly anything to eat. When we got into England all open land was filled with trucks of all kinds, tanks and stockpiles of supplies. We arrived in Exeter November 20, 1943. The trucks for E-9-15 and E-9-17 had arrived before us. Beside our three shop trucks they gave us a personnel carrier. We had not thought about how ten of us could ride in three trucks. A personnel carrier is about twice the size of a Jeep, and with bench seats on each side of the back. It was large enough for all ten of us and we used it to run around together. We left with our four trucks November 29, 1943 and headed for Plymouth, England, arriving December 1, 1943 at Martin Wharf. There were thirty sailors and a lieutenant, and crews for ten support boats. We bunked in one of two Quonset huts next to a bridge on the dock. There was one small building with one large room with tables, a small kitchen, toilets and showers.

Our job was to maintain the ten support boats. They were approximately thirty feet long, with twin diesel engines, and equipped with two rocket launchers with 2 racks of 4 rockets. The rocket launchers were not mounted on the support boats but had the brackets for mounting them. They would take them down to the river and out the inlet to the English Channel and make practice runs to the beach. These runs were very hard on the boats. They would take the boats out about one-mile and then come straight for the beach pretending to fire rockets. About two to three hundred feet from the beach the coxswain would pull one throttle in reverse full speed and spin the boat 180 degrees, then push the throttle full forward leaving the beach. This was very hard on the boat and engines. They would always come back in towing one or two boats. They were blowing holes in the tops of the pistons. The lieutenant reported this to the high command. We installed twenty new engines,stopping the problem.

May 12, 1944 we left Plymouth, England and went back to Exeter, England. We boarded the S.S. Wheelock May 24, 1944 with Commander Task Force 127 for the invasion of Europe, Operation “Overlord” June 6, 1944. Everywhere you looked you could see ships, from the shores of England to the coast of France. All the stock piles of equipment, supplies, soldiers and sailors were on the way to the greatest invasion ever undertaken. Before sunrise troops were being loaded in landing craft forming groups of large circles waiting for the signal to storm the beaches. The bombers and fighter planes started bombing, the ships started bombarding. The sound was deafening and the air was pressurized. On Omaha Beach the Germans were waiting for us. They had machine gun placements all across the hills, four pillboxes with eighty-eight caliber cannons. The beach was mined, plus obstacles. When the landing craft landed on the beach and dropped the ramp the Germans would fire an eighty-eight right into the boat. Many of the craft had holes punched in the hull from the obstacles or land mines. The fighting was fierce.

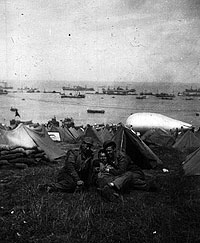

Around 4:00PM our four trucks were loaded in four landing crafts LCM’s. We climbed down the side of the ship on netting. Don Call and I were in one of the trucks. We proceeded to waterproof our truck. We were in a group of twenty boats circling for eternity. At this point I was scared to death. I could see my life pass before my eyes. We did not get on the beach until almost dark. I was driving the truck. There were so many sunken boats, tanks and trucks on the beach we had to land way left of our target. They dropped the ramp and I let out the clutch and the front of the truck went off. You didn’t know how deep the water was going to be. We were lucky we had only about three feet of water, about up to my knees. When all four trucks were on the beach a soldier told us we had to leave the trucks where they were until morning.

There were too many bodies on the beach to drive, and the whole beach had not been checked for mines. We got our tool belts out of the truck and walked down the beach. We found two LCVPs that the cables on the ramp had broken and they could not raise the ramp. The ten of us lifted the ramp and locked it in place and they got off the beach. We were also able to get one engine started in one LCM. The crew did not want to wait for the other engine to be fixed. The ships were still firing their guns and bombers were still dropping bombs. I could see planes pulling gliders. Every so often a German artillery shell would land on the beach. Also, several of the landing craft set off mines. That was the longest night of my life. We did not sleep for days.

There were a lot of soldiers on the beach. Some were recovering bodies, taking them farther up on the beach and lining them up to be removed in the morning. Others were taking care of the wounded and putting them on landing crafts to be taken to the hospital ships in the channel. We started helping the Army pull trucks out of sunken landing craft. Some trucks were pulling artillery cannons and loaded with shells. Some had supplies, others were empty that had brought soldiers that had left. We were also removing obstacles. Some time after midnight German fighter-bombers approached the beach and all the anti-aircraft guns on the ships started firing and the soldiers started hollering to get under the trucks. Tracers lit the sky, and flak was coming down like hail. This would only last about thirty minutes, and then it was back to work. This happened four nights. The windshield in one of our shop trucks was broken and all of them had holes in the roofs.

There was only one road off the beach and that was on the left hand side coming in, down where we had landed. There were still a lot of landing crafts bringing soldiers. Most of the boats were LCMs or LCVPs. They had very little difficulty landing, unloading and getting off the beach. At dawn we could see the entire beach and couldn’t believe all of the damage. There were hundreds of bodies in the water around the sunken boats. Many of the landing craft could not come to the beach because of the junk. They had let soldiers out of the boats in four to five feet of water. The soldiers had heavy packs on their backs, plus guns and ammunition. Those who lost their balance drowned. Without the soldier’s help it would have been impossible for the ten of us to clear the beach. The first place the shop trucks were was almost useless.

It took all three trucks grouped together for power. We needed more portable equipment. We were able to get two Jeeps and our own personnel carrier. We removed the back seats, and the Army gave us a portable electric welder, twenty pony gas tanks and two racks for them. We had the fittings. They also gave us a tractor with a two-wheel boom crane that the cable from the winch went up the boom. The shop trucks gave us a base to keep supplies and served as a base to sleep under and protect ourselves from the air raids.

We could back the crane into the deeper water and close the ramps on sunken boats, and we had two pumps that pumped 500 gallons per minute each. If the boat floated we towed it out by the ships they sunk for a breakwater, lowered the ramp and came around in front and pulled our boat on the ramp to sink it. We did the same thing with the boats we patched. The LCVPs that could not be patched were pulled up on the beach and run over with the tractor and smashed and pushed into a pile. Before we moved a boat the body recovery guys would inspect the boat for bodies. In some cases there were bodies under the boat that had drowned in the landing before. Some were also caught in the prop. For a week or so two guys would go out with us when we sunk boats and pickup bodies that were floating in the channel. We later gave them an LCVP they used.

Planes were flying around the clock, one line coming from England and one line going back. Every so often you would hear a different sound and lookup and see a plane with an engine on fire. During the three months we spent on the beach we saw four or five planes when the crew would bail out and the plane would go down in the channel. One crashed about half a mile off the beach and exploded. You could feel the ground shake and large waves came up on the beach. One other twin engine plane was in trouble and turned coming back toward the beach. When it was about a thousand feet from the beach the pilot landed in the water and slid onto the beach. No one was hurt. Kilmer and I were welding a patch on a LSM when two sailors from the recovery teams ask if we could cut a steel plate for them. We took our cutting torch and the tools we thought we needed and went with them. We climbed on the deck behind the two sailors and they opened a hatch to the engine room. A sailor had been sitting on a metal toolbox against the bulkhead when the boat landed on a mine. The deck plate had curled up, pinning him against the bulkhead.

There was only enough room in the engine room for Kilmer and me. One of the sailors handed down the tanks. We thought the bottom of the plate was the best place to cut, about two feet wide. Kilmer lit the torch and I took the fire extinguisher off the bulkhead to extinguish the dead sailors clothes. We had to stop at least three times to vomit. The two sailors on the deck didn’t say a word or laugh at us. When we got the plate cut loose one of the sailors told us to leave it, that they would remove the plate. We handed up our tanks and climbed out. They thanked us and we left. I can hardly write this without crying. The sailor was no older than I was. With the help of the Army we had most of the beach cleared of the small boats, trucks, tanks and junk. Just a few days later we had a storm about like a hurricane. It did as much damage as the invasion. The Navy finally sent in the C.B. with bigger and heavier equipment.

In late 1940 my brother Garnet was home on leave from the Army. He told me if I should decide to enlist in the service to join the Navy. He said I would have a warm, dry and clean place to sleep and would have warm food to eat. This was my home on Omaha Beach. I spent half my Navy time with the Army. We didn’t stay dry and warm, and we didn’t have hot showers. We ate “C” and “K” rations.

This church was in a town just a short way off Omaha Beach. The top of the bell tower was blown off. They still held church services in it. We left the beach September 15, 1944 with the Army and went to Cherbourg, France, arriving two days later. We only took our four trucks. We had not been paid for four months. We asked if we could receive our pay and was surprised to find out we had received a rate change to Petty Officer 1st Class (CM1C) on August 25, 1944. Willis was promoted to Chief. When we reported in we looked like bums. Our clothes did not match, were stained, and some had holes. They did not have a Navy clothing store in Cherbourg yet so they supplied us with Army fatigues. We were also given a mobile crane that was all hydraulic. On September 25, 1944 we were assigned to the Third Army for a secret destination with ten other sailors. They were the crews of three LCVPs. We came into a small town and a sniper in a church tower fired two shots. One soldier was hit, but not life-threatening. We were some way back from the front of the convoy. One of the tanks on a tank mover started firing the machine guns and fired one round from the cannon into the bell tower and one round right through the front door. Two trucks loaded with soldiers moved up and surrounded the church throwing hand grenades in the windows. When they went inside they found a woman dead on the stairs to the tower.

We arrived in Dinard, France September 28, 1944, back up to the front lines. There was an island off the coast that had a fortress with eighty-eights facing the sea which were shooting at ships. They had no defense from the back. The fighting was still heavy east of Dinard. We put our five units in the courtyard behind a hotel, and the three boats down the street in a park. The colonel told all of us to stay in the hotel lobby and not go any place else in the hotel. He told us to get our sleeping bags and rations for that night and the next morning, and then get back to the hotel lobby and not leave until we got orders from him. The ten boat crewmen had not been under fire before. You could tell they were scared and of course we were not overjoyed. We got in our sleeping bags about 10:00PM. We could hear artillery firing and planes bombing. We were not too bothered by this. I doubt that the boat crew guys slept.

At 6:00AM the Army started firing 105mm and 155mm cannons over the hotel. Twenty sailors were standing straight up in their sleeping bags. Try that sometime in a hurry. Shortly after that P38 fighter planes were dropping napalm bombs on the island. They kept the island burning for days. The next morning the colonel came by and told our chief and boat crew chief that we could walk three blocks either way on the main street. We could go in groups no less than ten, and we had to take rifles. Only three or four shops were open. At the end of the first block was a boarded-up photo shop. Kimble could speak French and he asked in one shop if the person who owned the photo shop lived in town. The woman told him yes. Kimble asked her if she would ask him to come to the hotel. That afternoon he came by. Kimble asked him if he could develop film. He said he had no electricity. And all of his supplies were old. Kimble told him we could supply the electricity and also pay him. He said he would do it so Kimble told him to come back that evening. Willis asked the colonel if we could do it and he said a week from Saturday or Sunday. The man came back that evening and agreed to develop the film a week from Saturday at 8:00AM.

The colonel told the chiefs he wanted landing craft ready Monday morning at 8:00AM. We went down at 6:00AM and unloaded the three boats off the trailers. The new crane was great. The three-man crew started one boat and ran it up and down the beach. At 7:30AM the colonel and a sergeant who spoke German got in the boat, put a white flag on the ramp, and headed for the island. Shortly after they landed on the small beach two Germans came out. They must have had sentries on the beach. They had only one exit out the back and it was built the same as a pillbox. You could not shoot into it. There were about one hundred heavily armed soldiers ready to go if anything went wrong. The colonel and the Germans only talked about five minutes. The colonel and the sergeant got back in the boat and came back. He told us that he wanted three boats ready by 7:00AM the next morning and that he had informed the Germans he would land on the beach. He left and ordered the artillery to start firing again. They fired all that day and night. Bombers also dropped regular bombs. That kept them from getting off the island at night. The colonel had soldiers posted on the beach all night.

We went down to the beach at 5:30AM and checked the boats. The same hundred soldiers came down at 6:30AM. This time they had added flame-throwers. The three boats left the beach at 7:00AM and headed for the island. The landing beach was not very wide. Two boats landed as far apart as they could and the soldiers fanned out on both sides of the entrance. When they were in place the third boat landed in the middle and the soldiers fanned out across the beach. There were also three tanks sitting in the water facing the island. The Germans came out with a white flag and surrendered. They loaded about forty in the boats and six soldiers got in each boat and came back with them. About one third of the Germans on the island survived.

When Saturday rolled around the photo shop owner showed up to develop the film and print the photos. Peck and I took the shop truck with the generator to the shop. I cut off the end of a heavy extension cord while Peck removed the front panel and disconnected the power lines coming into the panel. Peck removed all the fuses and wired the extension cord. I started the generator and plugged in the cord. He only put in the fuses that were needed. The photo shop owner setup everything and developed six rolls of film, and then printed ten copies of each negative. They came out all sizes because he had to use whatever paper he had. He told Kimble he had never printed that many prints in one day. Kimble asked him how much he wanted. He told Kimble in French what amounted to about one hundred dollars. We all had four months pay so we decided to give him twenty-five dollars each. He had not made any money in his shop for over a year, so he was pleased. Peck rewired his panel and we finished up at 6:30PM. We divided the pictures when we got back to the hotel. We showed the pictures to the other sailors and the next day to the colonel. None of them was at the Normandy landing and they couldn’t believe the extent of the damage. This was from a colonel who wouldn’t think twice of wiping out a whole town.

The three boats and crew left Dinard on October 12, 1944 with an Army escort back to Cherbourg. We left October 14, 1944 with an Army escort to Le Havre, France. The soldiers were going back for R&R. We reported to the Navy Command in Le Havre October 18, 1944. They were puzzled to see ten sailors in Army fatigues. The chief explained why. They sent us to a Navy supply warehouse to be outfitted with Navy uniforms. We reported back and were sent down to the docks. We were told we could stay upstairs in the office building. Downstairs were the officers of a black DUKW company. The black soldiers were staying in warehouse down by the docks.

There was a deep-water port where ships with larger equipment could dock for unloading. The DUKWs would go out to the ships anchored in the harbor and bring in pallets of supplies and store them in warehouses for shipping to the front line troops. Our first job was replacing an engine in a destroyer escort. The Germans had placed explosives on the legs of two big cranes on the dock and two smaller ones on the dry docks. We used cutting torches and our crane to clear the ones by the docks. That gave room for two more ships at the dock. The cranes in the dry docks had landed on nine small boats, four in one dry dock and five in the other. We cleaned all that out. The Germans had put explosives on the door to the dry docks and the pump house. The Army used the dry docks to dock their four tugs, which also gave them more room at the main docks for ships.

We ate a lot with the black officers downstairs. There were about thirty of them. They had a large mess hall in one of the warehouses. There must have been two to three hundred blacks scattered throughout the docks handling incoming and outgoing equipment, ammunition and supplies. They cooked food in the mess hall and brought it to the dining room in the office building. Whites and blacks did not socialize in the military back then but we spent time and talked a lot with them. The DUKW company was straight down at the end of the warehouse behind the office building so we spent more time with them. One man had a banjo and two had harmonicas. Some evenings we would go down and listen to them play for two to three hours. They were good.

There were dozens of crap games. One night I stopped to watch, and in fifteen minutes lost $150 (in French money). I didn’t have the slightest idea of what I was doing. Don Call, Peck and I went out walking. A group of black guys were all talking at once. We walked over to see what was going on. They were betting one guy he couldn’t drive his DUKW off the dock. The water was eight feet below the dock and at least twenty feet deep. I told one of the guys I’d bet $100 that he couldn’t do it without sinking the DUKW. A lot of the guys that heard me wanted ten or twenty dollars of the bet. Call and Peck also said they would bet a hundred. I went back to tell the others to come and make an easy hundred dollars. They came with me and had all the takers they needed. Other soldiers were making bets. Don and I got the crane with one pump hanging from the boom and parked it at the end of the warehouse on the dock. The guy drove his DUKW between two warehouses about three hundred feet and out of sight of the office building.

He got no more than forty miles per hour. He went off the dock and hit the water nose first. The well deck filled with water and the DUKW sank. He came floating out and all the soldiers started laughing. Then they got scared. Three others jumped in the water and two others got a sling from another DUKW and put it on the hook of the crane. Kilmer dropped it to the four guys in the water and they each took a cable and had to make a number of dives to hook them to the sunken DUKW. Kilmer raised the DUKW to the surface and we pumped out the well deck and raised it up on the dock. Those guys were all over that DUKW and started cleaning it. They had their own mechanics. Willis was holding our bets. We left with the crane and the pump. We also left with $1,000 of their money. I would like to give those boys a lot of credit for their contribution in winning the war. They worked around the clock handling the supplies coming in and going out. On April 15, 1945 Chief Willis received the second orders for temporary duty, this time with the Government Air Transportation for the U.S. Naval Technical Mission for Europe. Of course, the destination was secret. The orders said we should take undress blues and warm clothing, and that we could travel in dungarees. We were also to take carbines and necessary ammunition.

The orders had a list of ten names, only three from our unit.

- Willis CMOMM our chief

- Robbins MONM3C

- Maxfeldt EM1C

- Capwell S1C

- Young RDM3C

- Call M1C from our unit

- Shaver CM1C from our unit

- Daly RT1C

- Cooledge S1C

- Rice S1C

- Smith C0X

The orders read; No entry will be made on page 9-10 of service records. What that meant was the Navy would not put in our records where we went of what we did. Screwed for the second time. The first time we met the other seven men was at the airport in Le Havre on April 16, 1945. The pilot told us to look out the windows as we approached Frankfurt. There were only eight small windows in the plane. Willis, Call and I stood behind the pilot and co-pilot looking out the front. Frankfurt had been a large city before the war. Now there was only one building standing but it was heavily damaged. We had driven through a lot of towns that were totally destroyed. Seeing it from the air is hard to describe. We could see American bombers higher and ahead of us, dropping bombs not too far east of Wiesbaden. The Germans did not send up fighter planes, but they sure did a lot of anti-air fire. We did not see any American planes hit. They dropped their bombs and turned back to England.

We landed the same day in Frankfurt, Germany. We were met by a Navy commander, his driver, and two Navy men driving a ten-wheeler. There was a personnel carrier with four sailors in it and a machine gun mounted in the back. We unloaded supplies from the plane into the truck. We went to Wiesbaden, Germany to Anheuser Busch’s estate. We had lunch and were loaded in the same truck and went to a warehouse. There were four more armed Navy men. Inside the warehouse were aircraft engines and other aircraft parts I didn’t recognize. The commander told us he wanted all of if crated. They had brought carpenter tools, nails and steel banding, but no lumber. The commander told us there was a lumberyard in town. We got back in the truck and went to the lumberyard but it was not open and there was no lumber. We went back to the warehouse and told the commander. He asked if there were lumber sheds. Our chief said yes, so the commander told us to go back to the lumberyard and tear down the sheds to get the lumber. We went back and proceeded to knock down some sheds. Someone saw what we were doing and notified the owner. He came in screaming. One of the four armed Navy guards who spoke German told him to go talk to the commander. He left and did not return. By the end of the day we had taken down three small sheds and loaded the 2x4’s and ¾ inch lumber in the truck and unloaded it at the warehouse. We went to Busch’s estate for the night.

That night we sat around talking and found out thirty men had been sent to Wiesbaden. Only ten stayed with us, the rest were down by the warehouse. These guys were trained killers, and also intelligence gathering. There were three Navy captains and four commanders with their aides, who were living in the main house. We did not see them much. One commander was in charge of the thirty sailors. He also told our chief what he wanted us to do. There was heavy bombing to the east all the time we were there. On May 2, 1945 we left Wiesbaden back to the airport in Frankfurt to return to Le Havre, France. We were the only Navy service men in Germany during the war. The Germans surrendered on May 8, 1945.

On May 12, 1945 we left our trucks and crane in Le Havre, France and boarded an LCI bound for Falmouth, England. There we boarded a troop carrier and arrived in Boston, Massachusetts on May 28, 1945. On June 9, 1945 we left Boston for a thirty-three day leave. I reported back to Chicago on July 12, 1945, and was transferred to Shoemaker, California on July 18, 1945. On August 3, 1945 I was transferred to the Industrial Command U.S. Naval Repair Base in San Diego, California. I was put in charge of dry dock crews numbering 250-300 men. I divided the men into three crews; Crew to take blocks out of the warehouse to dry dock. Take blocks from dry dock to crews that cleaned and painted them, then return them to the warehouse. Crew to remove and set blocks in three dry docks. Crew that cleaned and painted used blocks. I was transferred on October 22, 1945 to San Pedro, California pending discharge. I was offered a chief rate if I enlisted for six years. I said “no thanks”. I was discharged November 11, 1945. I had to get a letter from our landlady sworn before a county clerk that Shirley was my wife living at her house so that she could board the train to return with me to Peoria, Illinois.

In 1989 Bud (my son) tried to find the other nine guys in my unit. The only one he found was Arthur Peck. I was glad because Al and I became friends when we met in Norfolk, Virginia, and are still friends today. Al, his wife, and his son and daughter-in-law came to Vero Beach for a one-day visit. Shirley and I had a cruise booked for April 1990 and asked Al if he and his wife would go with us. They did, and we had a good time. Al said he had tried to find all the guys ten years before. He said Willis and Kochelis were dead, and I think he found Parker in Michigan. It would have been great if the ten of us could have had a reunion. I still talk to Al three or four times a year.

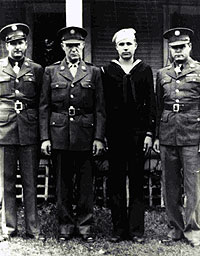

Garnet enlisted in the Army in the early 1930’s and served four years in Panama. He re-enlisted and was shipped to the Philippines. He came home on leave in late 1940. After his leave he returned to the Philippines. World War II started when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. They later had to leave the Philippines and went to Australia. They worked their way back through the islands back to the Philippines. He was one of McArther’s staff. He did not see combat. Garnet retired after serving twenty-two years. Dad joined the Illinois National Guard and was a night security guard. He remained there for over twenty years and retired. Jim joined the Army and went to the Pacific and made landing in the islands.

He came home on leave, and then was sent to France. He was wounded and sent to a hospital in Le Havre, France. He received a letter telling him that I was in Le Havre. A medic checked with headquarters in Le Havre and they told him where I was. He told me Jim was in the hospital. I had a chance to visit him three times before they shipped him back to the states. Jim was the only one to receive a Purple Heart. He was also the only one to serve in the Pacific and Europe.

Robert K. Shaver