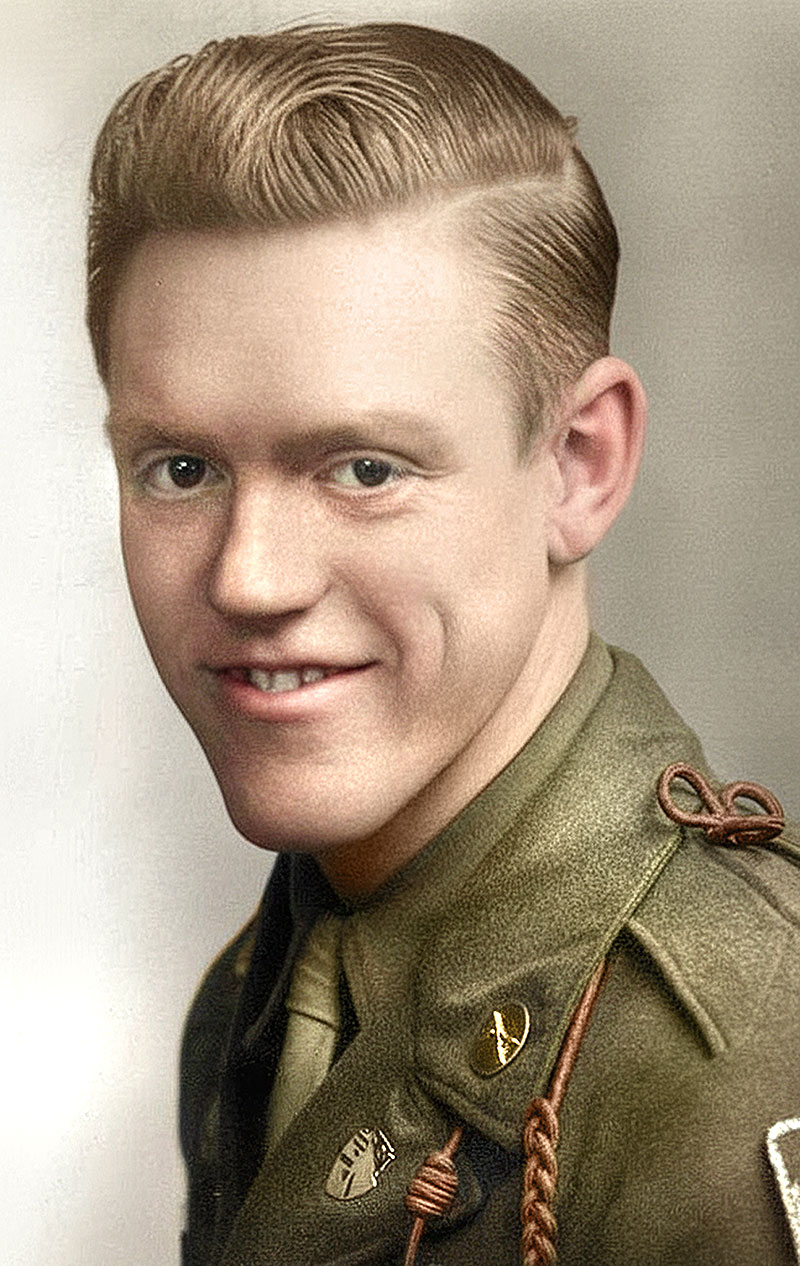

The story of Philip Stressel is a poignant account of an "infantry replacement" one of the thousands of young men rushed into the European theater to fill the gaps left by the brutal winter of 1944.

Training and the sudden Call to War

Philip began his journey at Camp Croft, South Carolina, in September 1944. His 18-week training cycle, which included both initial infantry tactics and advanced weapons training, was interrupted in its 15th week. The German Army had broken through Allied lines in the Ardennes Forest, the Battle of the Bulge and the need for replacements was so critical that Stressel’s training was cut short by three weeks.

Before shipping out from Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, he underwent a final physical and was issued a personal M-1 Garand rifle, which he had to clean of its "Cosmoline" preservative using scalding hot water from the latrines. In a display of the Army’s relentless efficiency, he was even called for dental work to fill cavities at 2:00 AM to prevent overseas emergencies.

Crossing the Atlantic

He boarded the Queen Elizabeth for the five-day trip across the ocean. The ship was packed; bunks were stacked six to eight high, even in the centers of rooms where metal pipes had been welded from deck to ceiling. Soldiers were issued color-coded badges and restricted to specific areas to prevent the massive ship from tilting. To foil German U-boats, the vessel changed course every seven minutes, leaving a snaking wake behind it. Stressel spent his time reading, sleeping, or trading his cigarette rations for candy and cookies.

The bond with Paul Taylert

It was during the journey toward the front that Philip met Paul Taylert, a fellow Private from Rochester, New York. Their friendship was sparked by a shared passion for music; while Philip was absentmindedly tapping a beat on a seat, Paul, a talented drummer and artist, noticed the "strong beat" and struck up a conversation. Bound by their upstate New York roots and their Catholic faith, the two became inseparable as they moved toward the combat zone.

Once they joined the 30th Infantry Regiment, they faced the grueling physical demands of the infantry together. They shared a pup tent in a wooded area, huddling in the fetal position under wool blankets to survive the bitter cold and snow. Though they were assigned to the same platoon, they served in different squads: Paul was tasked with carrying a heavy .30 caliber machine gun, while Philip carried two metal ammunition cans that felt like 100-pound weights during their silent night marches.

The Bar-le-Duc incident

After landing in Southampton and crossing the English Channel to Le Havre, Stressel began the journey toward the front lines via train. During a stop at the French town of Bar-le-Duc, he and several others snuck away to a local restaurant. Stressel, a talented linguist, enjoyed testing his high-school French with the locals, but the group lost track of time. They watched in horror as their train, carrying all their equipment and rifles, disappeared into the distance.

While waiting for a later transport, the group was detained at gunpoint by French security police after someone jokingly shouted "Achtung". The police, still unsettled by the war, eventually released them to catch a later train to rejoin their unit, where they were issued new equipment to replace what they had lost.

Seven days in combat

Stressel eventually joined Company K, 3rd Battalion, 30th Infantry Regiment, a key component of the 3rd Infantry Division. Historically, this regiment was nicknamed "San Francisco’s Own" while the division was famously known as the "Rock of the Marne."

His "baptism of fire" occurred while pinned down in an open, frozen field. He watched as two American tanks moved forward to support them, only to be incinerated by German 88mm fire "Whoosh-POW, Whoosh-POW" in a matter of seconds. Later, he encountered a horse wounded by shrapnel and, with his commander’s permission, humanely put the animal out of its misery.

The psychological toll of the war became evident during a brief encounter following a heavy German bombardment. Philip found Paul in a large excavation where his unit had taken refuge; Paul looked "terrible," possessing a "vacant look" that signaled the trauma of the intense shelling he had just endured. That was the last time Philip saw his friend before being wounded himself.

The final foxhole

The defining moment of his service happened on the morning of February 3, 1945. Stressel was sharing a foxhole with his Squad Leader, an older man who spoke of his wife and two children waiting for him at home. As Stressel knelt to heat water for coffee over a Sterno tablet, a German "tree burst" artillery shell exploded directly above them.

The blast killed the Squad Leader instantly with a hit to the spinal column. Stressel survived, but his steel helmet was dented and he sustained multiple shrapnel puncture wounds in both knees.

Recovery and the end of the war

Evacuated to a field hospital in Namur, Belgium, Stressel was treated for his wounds and a severe case of "trench foot". Doctors decided to leave the shrapnel in his knees, suggesting it might eventually work its way out of his skin years later. He was recovering in Worms, Germany, on May 8, 1945, when a movie screening was interrupted by a PA announcement: "The war is over, Germany has surrendered".

Though he had only spent about seven days in actual combat, the experience left him with the lasting philosophy that life is a "big crap shoot" where survival is often a matter of pure, unpredictable chance. It was not until the war in Europe ended that Philip was finally reunited with Paul Taylert, both men having survived their harrowing time at the front.

Excerpt and thank you

This is an excerpt from the story that Phillip wrote after his military service. A big thank you to his daughter Linda for sharing it with me. If you are interested in the written story please click the "Check out the book" button.