Out of high school in June of ‘40, I joined Ford Motor Co. as an apprentice tool maker in Feb. ‘41. (Two weeks before the BIG STRIKE.) Drafted in Feb. ‘43 and sent to Ft Bragg for basic training on 155 mm long tom rifles. After the 3 months training, 90 % were called out and marched off. A couple of fellows were kept as cadre to train the next batch and two of us were told to pitch our tents between the barracks. We did KP, odd jobs, spent a few days in the hospital and stayed out of the way of those things with jump boots and Eagles or AA on their shoulders when in town (Fayetteville).About the end of the next cycle, they put the two of us aboard a 6 by 6 and drove us off. BUT to where? 506 Parachute Infantry!!! The division was out on maneuvers and we were thrown in a casual company of a little bit of everything. Welcome to the 101st Airborne Division!

After a few nice summer weeks, I was assigned to the 321st Glider Field Artillery Bn, Btry “B”, Sgt. William Plummer’s Gun Section; Cpl. “Cokie” Crim, Gunner; and Pvt. Stan Rosberg, official procurer. It was Bill’s job to assign Stan to KP when ever we were on an overnight so that Stan could procure a can of Pet Milk for the section coffee. They liked the fact that I took my coffee black. Some time, during this period, I got a furlough home as I have a small studio picture of me in sun tans with the 101st patch but no glider on my GI hat. My mother objected to my ending letters with “Your Flying Cannoneer”, I changed it to “Love.” Between basic and overseas, I put in for officer’s training (90 day Wonders), sure and I still can’t get right face and left face down every time. I was acceptable but the quota was full; technical school to become Cpl./T or Sgt./T but was turned down. I had enough points for OCS but not technical school - go figure. I thought I wanted to be a fly boy but I probably would have washed out and ended up in 106th and been wiped out. Just before we shipped over seas, I asked the btry Clerk what happened to my Air Force application. The clerk said that “Our Fearless Leader” had turned it down as I was too valuable!!! Huh? I had been with the unit for about 3 months. Valuable??? Sure!

Camp Shanks was supposed to be guarded but some fellows claimed they made it to New York City. Our English troop transport was noted for bad food, lots of guys getting sea sick, & the temptation to sleep on deck to avoid the sweet aroma of the hold but the North Atlantic was too cold in late October. England, a train ride and then Whatcombe Farm in the morning. The cooks must have been shipped in early because there they were ready to slop it on our mess kits and the drums of boiling soapy water and drums of “rinse” water. Like all the low lifes (Pvts) in A & B Btry I was assigned to a horse stable ( four men to a stable), handed a large cloth bag and told the straw was out in the field. Oh Joy! First you had trouble staying on the big lump and then you had nothing but a straw dust. Stan Rosberg was assigned to live and train with a unit of the 1st British Airborne Division while we got an English soldier in return. Our soldier wore his British uniform, saluted English style (you have got to see that) and ate our American food. He was a good soldier.

We assumed that we would ride gliders into combat. 321st, “B” Bty had Cpl. (Crim) and 1st Sgt. (Shea) and I think a Capt. (Skinner?) who were deathly sick from even coming close to a glider. One of my fond memories is riding Co.-pilot on a training flight, some one was sick or something. I didn’t like it when we went over 150 mph as the wings would start to flap. Cokie and I were assigned to ride a glider in a simulated invasion mode but they changed their mind and we just loaded sand bags. We loaded a British plywood Horsair.(?) It ended up lodged against a tree.

Then we were told to waterproof our cannon, jeep, etc. We were going by boat. Apparently, most of the people were assigned to the Susan B Anthony but I was assigned to the John S Mosby. Who was I with? I turned to some one, a Cpl. or Sgt., and remarked that they were loading us with the unloading chart. Our pea shooters were loaded down in the hold while the 6 by 6s were loaded on deck. That some one just shrugged his shoulders as if to say, “What can I do about it?” Some where in the ocean, they ran us by a sand table to show us where we would be embarking. In two minutes, we were supposed to know where we were to be. Sure! Finally, the day dawned, the navy was firing their big guns and we just sat there watching the show. 1st Lt. Fred King claims that he saw the Susie hitting the mine and going down. I may have but the memory is very dim. We just sat there! We had the guns.

According to Mission Accomplished, on the morning of June 9th a small boat pulled along side to find out who we were and we were told that they had been looking for us for two days. First they had to off load those 6 by 6s, then they went down in the hold for our pea shooters. By then it was late afternoon and drizzly. Just as I was given orders to go over the side, Jerry came in shooting up the place. I climbed over on to the rope ladder which was swaying back and forth, the separation between the ship (boat?) and the landing craft would get smaller and larger, ocean in between. Mrs. Nasea’s little boy Johnny was twixt and tween but Jerry finally went home and I finally got onto the landing craft. The landing was uneventful and I spent the night, on the beach which by this time was swept clean, a lonely damp and cold boy. The next night I was assigned with several others whom I barely knew to an out post on guard. “Did some one out there call halt?” It was the Red Ball Express and boy did they do the job.

Combat! A slit trench 1-2 ft by 6-8 and deep behind the gun. Due to some mix up, we not S/Sgt Thibodeau’s gun section were the lead gun. This meant we did the initial firing and then the rest would fire for effect. Rather than sit around I assigned myself the job of making sure we had the number of powder bags that HQ asked for and that the fuse had the requested timing for aerial bursts to shower hot jagged metal on enemy backs, war is nasty. On two or three occasions, Sgt. Plummer, Cpl. Crim and I fired at night. Soften up them Jerries so they wouldn’t give our infantry a hard time. Bed check Charlie came over about 11 PM, we dove into the slit trench but he did no damage. We slept in the slit trench which we partially covered with the card board shell coverings. One morning, a spider and I climbed out of the trench together, the spider was fine but I had a fat lip.

After we had fired for a while, Plummer had to declare us temporarily out of action. The spade on the back of our gun had dug itself into our slit trench. And then there was the night, I held up the WAR! During the day, we had two stakes lined up in front of our gun (standard practice). The gunner Cpl. would twirl his sight so many degrees left or right depending on the Forward Observer’s target. The gunner would then line up his sight with the stakes and he would be set. Our elevation would be taken care of by the Number 1 man who would actually pull the cord to fire the gun. In the night, the gunner could not see the two stakes so the practice was to attach a flash light to a stake. I went in front of the guns to attach that light and that OCS candidate GOT LOST. Come on! We were in a football sized field surrounded by mounds of dirt and hedges, the guns were at the back and the stakes were near the front and I GOT LOST! I volunteered to lie down and let them shoot over the top of me but some one else had lit the light and I got back. I had held up the war.

It was the Fourth of July, we had been pulled back in reserve. We had been herded into a trailer, stripped, showered and given fresh clothes. It was the Fourth and we were aboard a bus headed for a beach. We passed a group of ladies doing there laundry in a near by creek, beating their clothes with paddles. We took off our clothes and waded out into the Atlantic Ocean and froze as we got wet. It was a beautiful beach but the water was cold. We got out onto the beach, laid down in the sun and we were dry. July 4, 1944.

In transit back to England, I was not proud of the treatment given out black soldiers, all I could do was to observe in silence. Back to the stables, given a furlough, flight to Edinburgh, find your way back, best flight I ever had, nothing but Eagles and Double A’s, pilot tossing out the regulation book, flying down on the deck over the moors and diving turning into that tea cup with a crack in it to let in the ocean, staying at a private residence, not being totally appreciative, wishing now I had names and address, taking the train back to London, being held up in Victoria Station by air raid, sleeping in Red Cross shelter, waking up to “Did you hear that buzz bomb? “What buzz bomb” I had been sleeping behind a howitzer. I took the train to Wantage, walked that 2-5? miles down a lonely rural road, and flung my last penny into the fields. Time to go to work!

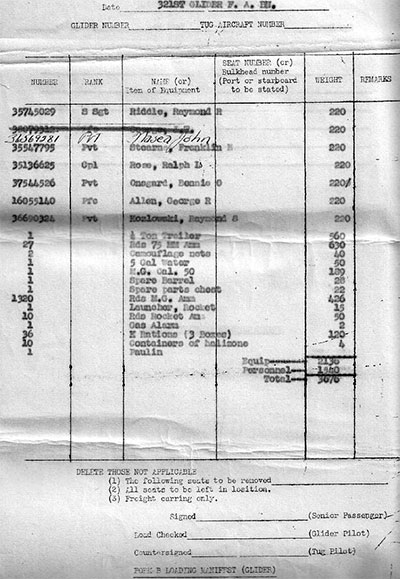

Two times we were alerted , the last time to drop behind the German Panzers and kill tanks Kill tanks with our little pea shooters? But third time is the charm, pack up and go to the airport. I found out that if you turn your helmet back wards and stuff your field jacket under the small of your back, you could sleep comfortably on the concrete run way. I don’t remember getting in the glider but I remember choosing my seat so I would be the first out. I remember all those nylon ropes strung out in front of our gliders. We did not have any fog so we could look down and see many patrol boats in the water, ready to pick us up if we crashed (I guess). I had the urge to pee but modesty kept me from letting go on the glider floor, an action that would cause me misery later.

As we approached the Dutch shore, we came under much small arms fire. One of the fellows reported sitting on his helmet, I tried to crawl up into it. And then it was silent. I guess we were over 101st held territory. I remember looking out and seeing the field, seeing the pilot let go of the rope. Some one asked if any one was hit, I felt under my pants and felt warm and wet. I looked out and found everyone on the ground, weapon ready. Supply Sgt. Ray Riddle pulled me out, I was the last one out. Using the 2 x 4s that held up the nose of the glider as a stretcher, they put me on the trailer ( we had a trailer with 75 mm ammo) attached to a jeep and pulled me across the plowed field to the aid station, with Cry Baby Johnnie crying, “Take it easy”.

The aid station was to our left behind a farm house, a foot ball field away. They patched me up and started pouring plasma into me.. Some how I got over to a convent or something. I remember the nuns or nurses or what ever they were. A bunch of us were lined up on the floor. That night we heard a lot of small arms fire. I think they were fighting for the bridge at Zon and we were not far away. It is funny, while I was scared during the small arms fire while in the glider, I no longer had any fear. I can’t claim that religion paid a part but I just put my trust that “they” would take care of me.

The next day we were put aboard an ambulance to go to Belgium. They had to stop because the road was under fire. I went through a series of field hospitals before landing in a Brussels City Hospital, partially under control of the British Army. I would go in an American Field Hospital where they put plaster from my left toes to my chest but leaving my right foot was uncovered. It was there that I first said “Good Night, Nurse” as they put me to sleep with sodium pentothal. I woke up in a British Field Hospital with plaster only from the toes of my left foot up to my crotch. The Brits were all wet. The “armor piercing 30?” tore a hole in my left thigh very high up and broke my left femur. I also collected three flesh wounds on my right thigh. The Americans must have gotten to me for I ended with my body suit. I am hazy about the number of field hospitals, go to sleep in one, wake up in an other. Who knows where I had been.

They had to catheterize me to urinate and when I got a laxative, they didn’t position me properly over the bedpan, what a mess. I remember in triumph being able to move my right heel side ways a bit. Thank GOD for even small favors. But then I had to travel in an ambulance thru the city of Brussels to the air port and every time we crossed a street car track, I was in misery. They put me aboard a hospital plane to England. With my suit of plaster it should have been obvious to all that I had no use for shoes but the hospital attendant had the brazenly stupid gall to ask me for my jump boots.

I was in a hospital some where in England, the ward was full of 101st and 82nd just back from Holland. I was given refrigerated whole red blood, I nearly froze, I didn’t finish the container. A distant cousin (Dr. John Stanley) , with a camera , came to see me. But he did not want my mother to see how bad I looked so no picture was taken. Some kind of officer came over with a box, “Do you know what this means?”, meaning the purple heart with a bas relief with George Washington on it. ”Yeah, it means, I got clipped”, he did a one eighty and walked away. They put a pin in my knee and attached a weight to it. Three months in traction and I am still sorry I did not try and contact my unit back in combat. I tried to play poker with the man on the bed to my left, the Captain doctor came storming in, my x ray showed that my left was out of alignment, I became a good boy. Then back to my suit of plaster and onto the Queen Elizabeth for the ride home.

Half way, the rope holding up my bunk creaked and I thought for a moment it was small arms fire. Staten Island in clean white sheets just as the Battle of Bulge for Bastogne got under way. Halloran General Hospital, Ft Benjamin Harris, Indianapolis for Christmas ‘44. With tape instead of a pin, more traction for three months and finally after 6 months flat, I got out of bed on crutches, carrying my left leg in front of me. Just after President Roosevelt died, I stood in the middle of the ward trying to make my left leg move. Do you know how to move your left leg, if you do, tell me I did it but I still don’t know how!

Hard Duty: We got up/had breakfast/ were the first off the tee/lunch/swimming/dinner/movies/bed time in clean white sheets. In the mean time, I had PT but formerly Gung Ho John was not too anxious, Japan lay ahead and I wasn’t too sure that I wouldn’t be sent. I do not have complete knee bend, would a more rigorous PT produced a complete knee bend or was too much stuff shot away? Perhaps the proudest moments of my military career came in around Orthodox Easter ‘45. Dad & I went for Easter Service at the Romanian Orthodox Church, breakaway St. Simeon, a large upper room above a store front accessed by a narrow stair way. Since we could not walk around the building, we walked in a circle around the room. I can still see Dad & Unchiu (uncle) beaming as I walked in full uniform with ribbons and with crutches. Similarly, I can remember the pride of Dad & Unchiu, as I visited them while they worked side by side in a small slaughter house from which they both retired.. Fond memories.

Discharge in October ‘45 at 150 pounds!/ Breakup with Helen, for which I am grateful/enrollment in U of D in Jan ‘45/Masters in Chemistry from Wayne State in late ‘51/marriage at 120 pounds! to Mildred on Sept. 13, ‘52. YES! Friday the 13th, in September, we will have been married for 50 years. Three kids, two grandkids, I owe a debt to GOD and my fellow man. I visit with fellow vets at the Detroit VA Hospital, 3 hours on Wednesday morning. As a Deacon in the AP Presbyterian Church visitation is a big part. I hope I am paying something on that debt I owe. Overall I had it easy. After 15 years at the Detroit VA Hospital, I got my 2000 hour pin.

John Nasea, Jr. Family Man.