Being born in 1925 I was drafted to the German Wehrmacht in 1943. Thereby, at the age of 18, I became a soldier of the “15th Grenadier regiment” in the city of Kassel (south of Hanover) Before that, since May 1943, I had been serving in a camp of the “Hitler Jugend” in Austria for children being evacuated from dangerous areas of Germany (e.g. the “Ruhrgebiet”), where important military targets were being bombed. Sending these kids to safer rural areas was called “Kinderlandverschickung”.

Atlantic Wall

After 4 weeks in Kassel I was transferred for further training and drill to the village of Salbris near Orléans in September 1943, thus joining the occupation forces in France. After a short period of time, on October 18, 1943 I was then transferred to Brittany, to the town of Pontorson near the famous Mt. St. Michel. After the first weeks in Kassel, where our service had been endurable, I had a very hard time as a recruit and a watch-guard. In January 1944 I fell with jaundice as a consequence of the very poor nutrition and had stay in a military hospital in Fougères (near Rennes) for 4 weeks. To my regret, this prolonged my time as a recruit and prevented me from being detached to Italy with my comrades. When the period as a recruit had finally come to an end, I was engaged near St. Malo to work on the “Atlantic wall”.

Back home

After St. Malo, my next intermediate station was a small town near Paris (from here first and only vacation within 4 years, visiting my parents back home). Shortly before the allied invasion started on June 6, 1944, I was transferred to my home garrison in Kassel. Here, running through different companies, I was lucky not to be sent to Rumania, which had changed fronts to form an alliance with the Soviet Union in August 1944 and had become a battleground for guerrilla attacks.

Arrested

Instead of going to Rumania I was sentenced to 3 days of arrest. I was accused of not having reported in time the theft of my brand new boots. Somebody took it away the night after we had received our new gear for the mission in Rumania. They claimed I must not have waited until the morning to report it, but had been obliged to do so in the middle of the night. Whereas I wanted to make sure that no “comrade” had fooled me. To me this was very unfair and my military “career” somehow changed direction. Looking back, I think this event maybe helped me survive the war. From Kassel, transfer eastwards to Erfurt (south-west of Berlin). I suppose this happened with regards to the plans to assassinate Hitler.

Operation Valkyrie

The most important military conspirators were General Friedrich Olbricht, Major General Henning von Tresckow, and Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, along with Claus-Heinrich Stülpnagel, the German military commander in France. The motivations of the conspirators in the July 20 plot were likely varied. Some, like Carl Goerdeler, objected to Nazi anti-Jewish policies and the general mismanagement of the war, which they believed was leading Germany to ruin. Henning von Tresckow was also deeply dismayed by the Nazis' antisemitic policies, and he privately described Kristallnacht as an act of barbarism.

After a successful assassination, well-trained troops would have been needed inside of Germany to win possible armed conflicts and disarm troops loyal to Hitler (like the Waffen-SS). After the attempt to assassinate Hitler had failed on July 20, 1944 the Wehrmacht carried out a march through the streets of Erfurt to demonstrate its loyalty to Hitler. Shortly after that I was then transferred to France to join the “Panzer-Lehr-Division”, counting among the elite troops on the invasion front.

Back to France

The transfer via railway took us 14 days, finally being unloaded at Versailles, because trains could not go further west. Arriving at the “Panzer Lehr Division” near Argentan on August 12, 1944, I was detached to the “Panzergrenadier Lehr Regiment 901”. The spirit I encountered here was different from what I had experienced before: the regiment had stood in heavy combats against the allied forces in Normandy and had suffered many casualties. Therefore we were welcomed as replacements.

Withdrawal to Germany

Then followed our withdrawal out off France in running fights, constantly threatened by American fighter-bombers until finally reaching the region Eifel in West-Germany. We took up quarters in Sinspelt (near Bitburg). In that area I was fighting in a combat group of my regiment, finally pushing back the American troops westward across the border to Luxemburg.

In October transfer eastward to the area of Rinteln (on the river Weser), west of Hanover. On November 13, 1944 again transfer westward via railway to the area called “Hunsrück” (south of the river Mosel), already in preparation of the “Ardennen-Offensive”.

Unexpectedly, detached to fight against American troops breaking through in northern Lorraine (near Diemeringen), we were sent on a 2 days’ march around Pirmasens. Our mission was to close the gap that had been cut into the German frontline. Heavy combats, lossy operations against the superior American troops. In an assault by night on December 2, 1944 my company was almost completely wiped out.

It was only with a large amount of good fortune that I could save my life, running zig zag like a hare across an open field, whereas a good comrade of mine was killed right next to me. Shortly before that I (meanwhile in the rank of a Private) had been assigned to the company staff as a messenger and therefore was riding in the half-track of our company commander Lt. Karl Neupert.

After that operation, the rest of our company was dislocated into the Eifel (north of the Mosel) and received replacements, some of them soldiers from air force units in blue uniforms without any infantry training and combat experience.

Our last quarters before the beginning of the “Ardennen-Offensive” were in Rodershausen. It was here with the morning-appeal that we received the command of the day. Target of the offensive: the conquest of Antwerp, cutting off the American supplies. During this appeal I received the medal of honor “Eisernes Kreuz, II. Klasse” (Iron cross, 2nd class) for the successful operations in Lorraine.

Battle of the Ardennes

In the late afternoon of December 16, 1944 we crossed the border to Luxemburg near Gemünd to occupy the bridge-head that had been set up by our infantry, the “26. Volksgrenadier Division”. For our tanks it was difficult to get ahead on the winding and narrow roads into the valley of the river Our. The first villages that were taken by our division were Holzthum und Consthum which had been left hastily by the American troops.

After that we advanced across the Belgian border to the encirclement of Bastogne. In the morning of December 20, 1944 our company was ordered to attack and take the village of Marvie (about 5 km south-east of Bastogne) in our half-tracks. There was no reconnaissance at all about the enemies’ positions to prepare our assault which then was carried out without artillery support. For the first time the American troops persistently defended their positions. Except for the half-track of the company commander, in which I was also riding, my company was completely destroyed (about 80 men in 5 or 6 half-tracks and 4 tanks, type Mark IV).

Mortar attack

The next day, on December 21, the rest of our company got into an assault with mortars, in which our company commander Lt. Neupert, taking cover on the ground right next to me, was killed by shell-splinters. It was not before 1972 that I found out about his fate when I visited Bastogne for the first time again and found his grave on the German soldiers’ cemetery in Recogne. The last time I visited his grave was in summer this year.

Until Christmas 1944 the village of Marvie was attacked a few more times and parts of it were taken. We were then supported by soldiers of the “26. Volksgrenadier Division”. I participated in more combats during the “Ardennen-Offensive”, our troops step by step withdrawing across the German border, which I crossed on January 31, 1945 as one of the last German soldiers. By the end of February from the area of Cologne our unit was sent on an urgent mission against Canadian troops on the Lower Rhine (near Xanten, Uedem). This was followed by our dislocation to the area of Krefeld.

Taken prisoner

On that occasion we attacked the village of Schiefbahn, held by American troops, with our tanks at night. The assault caused many casualties on the American side. 23 American soldiers were taken prisoner and I got the order to take them back away from the frontline.

A few days later when I surrendered to the American forces in Schiefbahn, near Krefeld, in March 1945 I was a Private in the Panzer-Lehr-Division. Transport to France then followed, going through the POW camps in Attichy, Chartes and Laon. Finally, we were handed over to the French. We were working in the woods as lumberjacks on the Chemin des Dames (battleground of World War I).

Liberated

Later I fell ill with typhoid fever. This then became the reason for being released earlier than expected. I owe this to a French military doctor in the citadel of Laon (Dr. Bertheau), who had a very human attitude and treated me with in a noble manner. I returned home on May 2, 1947, a few days before turning 22.

Many details come into my mind while looking back. All in all, these were 4 years of my life which have been engraved in my memory and have deeply influenced my personality. These experiences continue to affect my thoughts and my attitude towards actual questions and discussions of today.

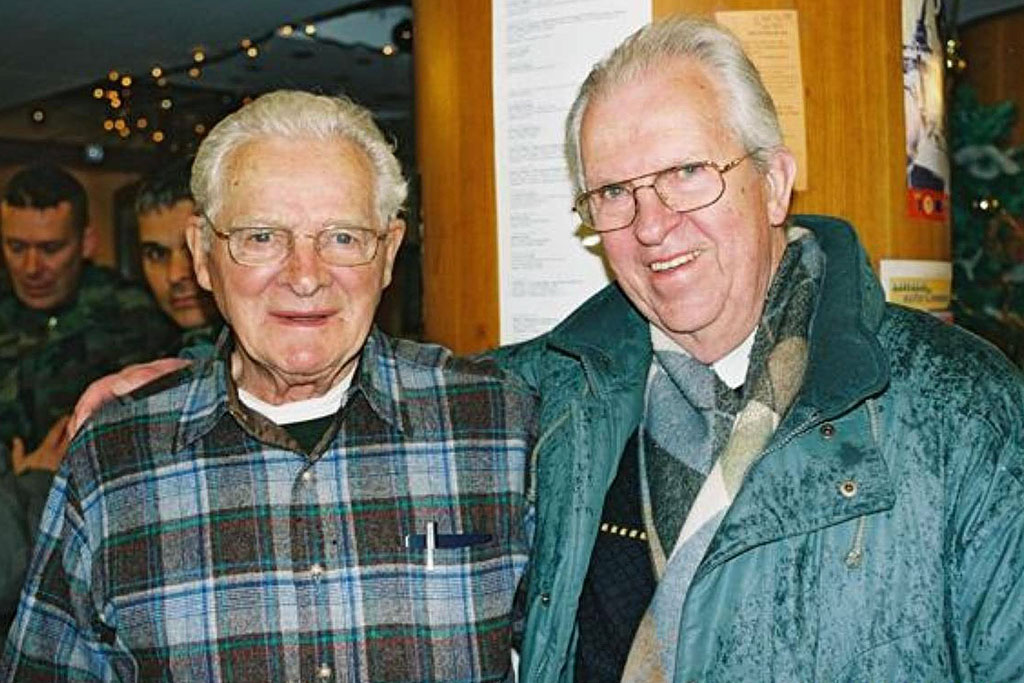

Donald G. Malarkey

Sixty years after they fought against each other in the Battle of the Bulge, Mr. Engelbert meets his former enemy: Don Malarkey (2nd Battalion, E company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division) over beers in Bastogne.

Both men suffered from Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) but as they learn how similar their lives have been, they bond like brothers, forgiving each other and forging a friendship that passes down to their own children. They formed a close friendship and Malarkey even traveled to Germany to visit Engelbert and his family. That friendship has been written down in the book "Saving my enemy"

As told by Fritz Engelbert

A big thank you to Volker and Matthias Engelbert, Fritz' sons for their valuable help with the story!