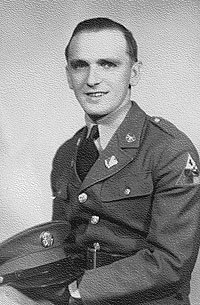

I am Eugene William “Lucky” Luciano, Serial No. 31048909, born in Torrington, Connecticut on April 20, 1916. I was a Technical Sergeant (Platoon Sgt.) NCO Squad Leader, Company 'C', 10th Armored Infantry Battalion, 4th Armored Division. Drafted July 9, 1941. Discharged October 26, 1945. Served at Camp Devens, Massachusetts, did basic training at Camp Croft, S.C., and was shipped to Pine Camp, N.Y. for armored training on October 25, 1941.

On December 28, 1943 we embarked on a ship called the Thomas Barry, a creaky old ship, named after a famous Navy officer. He probably was the founder of the American Navy during the American Revolution. As we sailed out of Boston Harbor, I could see men on the roof of the Charlestown Navy Yard waving us on. I know my brother Mario was there.

The ship rolled with each wave, creaking as she went and many soldiers were seasick. We were passengers loaded in bunks to capacity - Thank God - with the whole convoy protected by destroyers and other naval ships, the crossing went well to a safe landing except for a mishap for two young soldiers washed overboard into the ocean by a sudden swell of a large wave. A destroyer was dispatched to go back for them, but they were never found. The Atlantic is cold and rough at this time of year.

Now the time had come - about four (4) years of training. We were ready. On July 9, 1944 we left our barracks for the shores of the southern part of England to embark up on ships to cross the English Channel. Goodbye England - Hello France. As our LCI's and LCT's approached the Utah beach, the debris was floating with G.I. cans, miscellaneous equipment and an occasional body bobbing in the water.

Our landing had to be delayed until the tide went out and the waters receded from the ships. After some time the ship's gate was unlatched and the half-tracks loaded with the men and equipment set upon the beach. The sight of many of our dead and wounded and the German prisoners waiting to be sent to prisoners of war enclosures was the realization of the dangers that laid ahead. "This wasn't maneuvers, this was the real thing and what in the hell am I doing here?" Over in the distance an enemy observation plane was seen twirling in rapid descent - shot down by land based gunners.

The time was mid afternoon on July 13, 1944. The battalion, having landed, went to the left, heading in the wrong direction, perhaps into the Canadian or English section or towards the enemy. Only when someone alerted the battalion about the mistake, and made the necessary change to move to our bivouac area which was near St. Mere Eglise and northeast of Perriers. It seemed so peaceful even though shellfire could be heard in the distance. After bivouac, with our vehicles around the perimeter of the field, guards were posted and we rested for the night. In the night, shells must have fallen in our area as shell holes were visible, but there were no casualties. One soldier getting into his foxhole, accidently shot himself and had to be evacuated.

The next day, many French people and especially young boys were very curious to talk to us and were elated to see our equipment and ask questions until the order was to cease and desist with information to not jeopardize our position. It began to rain and it continued all day long. As time passed, the troops were restless and becoming impatient standing around for three days with very little activity. Many of us , to get out of the rain, would go to the edge of the field and stand under the trees. Remembering back to that time - my friend Mickey Dwyer and others got the bright idea that since we were out of sight, now was the time to unload and bury all of our impregnated clothing at the base of the trees. Many things were impregnated against the affects of water, etc. and perhaps a gas attack.

About the fourth day some "90-day wonder" (a new 2nd Lieutenant) had us all in a skirmish line advancing, slowing, and sticking our bayonets very carefully into the ground. We were to clear the field of possible mines. Of course, the men had already walked over the area on the previous days so it seemed so foolish to be checking it now. All this time, we were anxious to get on the move. The front lines were only a few miles ahead and the beachhead was a very small area. Troops were being landed continually and sooner than later we would have to enlarge the area to accommodate all the equipment being put ashore. One important detail is that the air cover and our air support of the area protected men and equipment from enemy counterattacks trying to push our backs to the sea. This is not how my impressions of France had appeared to me in my youth.

On the day of July 17, 1944, we relieved an infantry division in the line. It was either the 4th Infantry or 29th Infantry Division. This is when I saw my first dead German soldier. He was laying beneath a large tree, bloated and seemed green to me. I notified my superiors, but they said the graves registration personnel would take care of all casualties. Then as we were ready to take our position in the line, a shot caught a lieutenant right in the middle of his forehead. He never knew what hit him.

This was at Periers, Raids and La Maugerie. We lost some of our men and suffered casualties. We helped evacuate a couple of boys from their front positions who were wounded and placed them in a ditch a hundred yards or so back. We gave them first aid and tried to stem their chest wounds and also sprinkled sulfa on the injuries. They were mortally wounded and one kept calling his mother, "Ma, Ma". As we were trying to ease his pain and dress the wounds some officer whom I did not know, told us to leave him alone and get back up on the line. We were still under fire, but the officer acted as if we were still on maneuvers.

I was scared but there was no place to go but back to the fire fight behind the stone wall. At nightfall, all turned quiet except the brbr-brbr-brbr-brbr of the burp gun to keep us awake. Being scared is not unusual. Good leaders hide their fears and act bravely when they are with their men on any mission or patrol to instill confidence to the men in the leader's ability. Any man in combat who claims he is not frightened or scared is not truthful. A brave soldier is also a scared soldier. The only soldiers, not running scared, are dead ones. Even though I came from a religious family, also serving the church as an altar boy, I became very lax in religion. How quick I found it in the foxholes, especially at Arracourt when we were under attack. There's an old saying, "There are no atheists in foxholes." How well I know. Thank God for our chaplains.

Some other emotions are home sickness, loneliness, and sadness. When hearing sentimental songs such as "You'll Never Know", sung by a 27 year old Frank Sinatra would give one a romantic and longing feeling and also "White Christmas", sung by crooner Bing Crosby would bring back wonderful memories of home. Suddenly, you are saddened and wistful. A soldier is not afraid to shed a tear or cry on the loss of a buddy on the battlefield. Happiness is shown by soldiers when a mission is successful and completed. These are some of the many emotions a soldier experiences.

In the night time, Captain Leighton called me to take a squad and keep contact with the companies of the battalion, on a patrol because the radios were silenced. I stooped and crawled with the squad using a password to make contact till early morning. The early morning hours were very hazardous and as we went along the road, mortar shells would almost have us zeroed in. The Germans had all the ranges for mortar fire already setup, especially at the hedgerows. As we stopped and then moved about fifty feet, one could hear the mortar shells and see where they landed, where we had been just moments earlier. That happened a few times and then it stopped because some of our guns in the rear were firing at their positions and they pulled back.

There could have been a spotter, back of our lines, when we were on patrol telling our position for those mortar shots - possibly French. Later on Sgt. Tessier said he shot a sniper out of a tree. Company "C" was pulled out of this line. I lost Pvt. Corcoran in action in this skirmish and Pvt. Holmes was with him when he got shot. When I peered over the hedgerows, I fell back immediately because of enemy fire. I jarred my helmet into the bridge of my nose causing injury. This was our baptism of fire.

The hedgerows were created by many years of Norman and French farmers clearing the debris and resulting undergrowth which formed borders for the fields. This formed a bank of hedgerows, four to five feet thick and high. On the 19th of July, we heard through rumors that efforts were being made so that the war would soon be over. There was joy everywhere. It never happened. This must have been the attempt on Hitler's life.

This same day we were sent on a mission led by Lt. Robberts to the right of where we were holding the line with "A" Co. We attacked and laid all kinds of firepower as we advanced only to later realize we were firing on some of our own engineers to the right flank. Being "green" troops, we were using-up our ammunition in rapid-fire, not even knowing what we were firing at. The German fire was more deliberate with mortar and sporadic bursts of their guns. No damage was done as somehow the situation corrected itself and we attacked and drove straight forward advancing perhaps 100 yds. or so until Captain Leighton fell mortally wounded. The attack was broken off and the line held. At nightfall Lt. Spencer and Sgt. Tessier went out to get the Captain under cover of darkness. He was still alive but died soon after so they said. For the next few days, there was an exchange of artillery and gunfire, but very little advancement.

The hedgerows were a stumbling block to us as the Germans had them all zeroed in. For the next ten days we fought at a standstill. We did not lose any territory or gain very much. A way had to be found to use our motorized equipment and when a soldier came up with the steel wedge welded to the bulldozer to cut through the 4 foot thick hedgerows so that the tanks, half-tracks, and guns could move through, and we could attack and use the training we learned in the Mojave Desert in California. Some of the material used to make these wedges of steel came from obstacles in the water and the beaches where their purpose was to prevent us from invading France.

Eugene W. Luciano