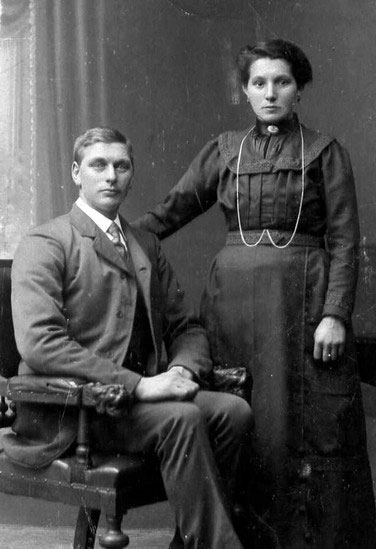

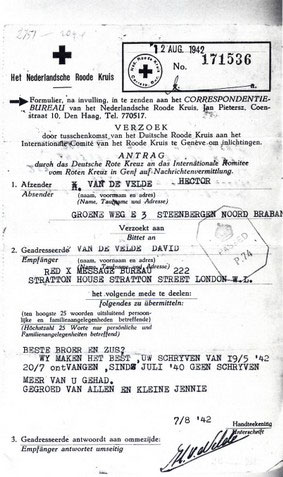

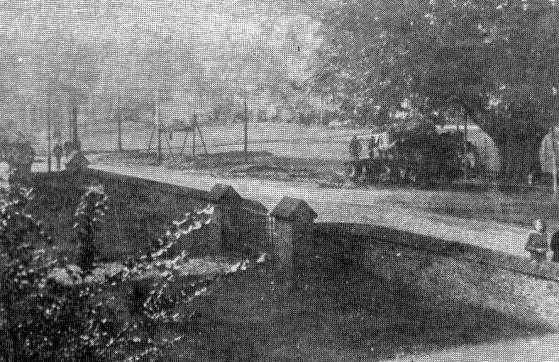

Prinses Irene Brigade veteran David “Daan of Daaf” (In the UK they invariably called him "Denny") van de Velde was born on July 9, 1912 in a small workers' home on the Oost-Groeneweg in Steenbergen, near the Van der Spelt farm. His parents were farmhand Cornelis van de Velde (1883-1951) and Johanna Jansen (1887-1925). They had five children together: Maatje (1908-1945), Hector "Torreke" (1910-1990), David (1912-1997), Lucretia "Jaan" (1915-1968) and Cornelia "Corrie" (1918-2007). The Van de Velde family belonged to the small religious community of the Dutch Reformed Church. Daan attended primary school in Steenbergen. He was a very good student and would have gone to the "MULO" if his mother had not suddenly died in 1925. This dreadful incident troubled him the rest of his life. He hated the Color black. The reason was that his father made him paint his favourite grey suit black, before the funeral. Daan was very attached to his mother and he later said that after her death, the warmth and cosiness had disappeared from the house. Despite repeated requests from the Headmaster, to his father for Daan to study, he had to work to bring in money for the family. He eventually became an apprentice machinist at the local Central Sugar Company.

Military Service

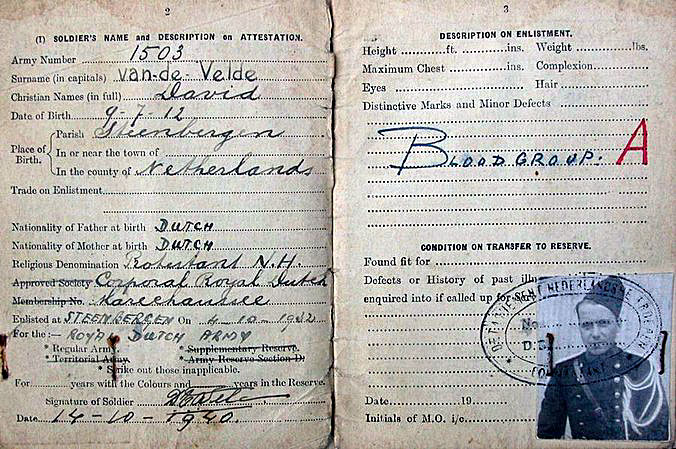

On October 4, 1932 he was drafted into the 3rd Infantry Regiment based in Bergen op Zoom. After six months he became a corporal, but then, due to budget cuts, he was made to take a long leave. In the middle of the crisis it was difficult to impossible to find a job. Through the mediation of Sjef Janssens from Breda, an uncle of his, who was with the KNIL, he ended up January 3, 1934 as a voluntary soldier in the army destined for service with the Police Force Corps. The training was in Nieuwersluis, near Utrecht.

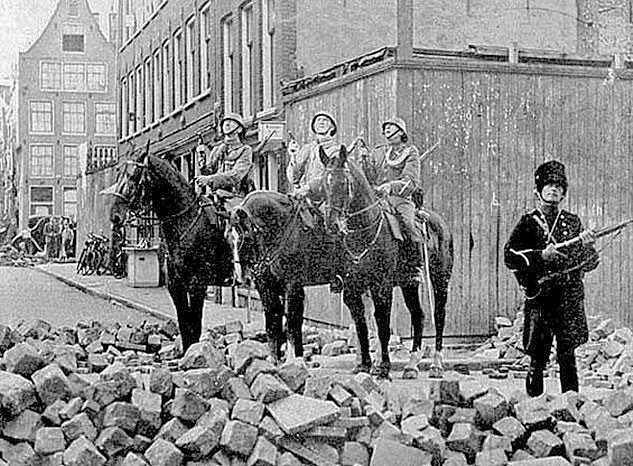

He was deployed in July 1934 in the so-called Jordan riot in Amsterdam. These were fierce riots by the unemployed in Amsterdam. He later said that the rebellious people threw down stoves and roof tiles from the windows on the upper floors of the houses. Shooting these people was against his conscience. "The people were so poor and hungry. You jsut don't shoot them. "

On April 4, 1935, his employment with the Police Troops was terminated and Daan ended up as a professional soldier "Marechaussee on foot" at the Depot Koninklijke Marechaussee. He was posted to the 1st Division and received his training at the Zwolseweg in Apeldoorn. In 1935 and 1936 Daan was posted as a military police officer in the town of Sluis in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen. He stayed at the house of the local butcher Gijzels. As a border guard, he was often asked to have his picture taken with female tourists, who were very charmed by that beautiful blue uniform. Since there are a striking number of photos from this period, there is a good chance that the ladies also liked the man in the fancy uniform! Daan therefore had good memories of this period. In the 1960s, when he could finally afford a car, he and his family returned to this area almost every year for a holiday.

After spending another short period at the Depot in Apeldoorn, he was stationed at the Marechaussee barracks on the Eindhovenseweg in Valkenswaard in the late 1930s. Here he was also charged with border security. The task was to combat rampant border smuggling. With his four colleagues Meulenberg, Koenen, Bacchus and Uiterwijk, he covered the surveillance area Aalst, Waalre, Dommelen and Borkel en Schaft on foot and by bicycle. It was the late 1930s and the residents in this part of Brabant were so poor,that they had to earn something extra to make ends meet. The small smugglers, also called "pungelaars", mainly smuggled butter, salt and sugar. Usually, butter was smuggled to Belgium, because the product was much more expensive there.

The Marechaussees who caught smuggling women sometimes held them in their office for a while, so that the melted butter dripped from the skirts from the warm stove. Others hid their contraband in rubber bags and let the border rivers such as the Tongelreep and Dommel do the transport. Daan once caught a man who wanted to free a parcel that got stuck in the bushes with a branch.

When his son Richard put his favorite 78rpm record "De Smokkelaar" by Johnny Hoes (Dutch singer) on the pick-up in the fifties, Daan told a lot about his experiences in those parts. He was very concerned with the fate of these small farmers and for that reason, he turned a blind eye to a smuggling attempt. Partly because of their poverty. He hated the term "Good old days".

German invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940

When war broke out in the Netherlands on 10 May 1940, the 273 Marechaussees stationed in Brabant were ordered to withdraw to the "Fortress Holland" (Fortress Holland is the name for the strategic core area of the Dutch national defense between 1922 and 1940. The area encompassed the part of the Netherlands that was considered vital and which should and could last for a long time and roughly coincides with the present-day Randstad. In the meantime, Fortress Holland turned out to be inaccessible, because German troops had already established a bridgehead on the Moerdijk-Rotterdam axis. The Marechaussee brigades therefore gathered in Roosendaal on 11 May 1940. When German bombers set large parts of Roosendaal on fire, the commander ordered the march to Putte (North Brabant). Subsequently, Daan and his colleagues left by bicycle, escorted by Belgian officers, across Belgian territory towards Antwerp. On the way, all kinds of fleeing Dutch soldiers joined. After a few hours they reached the Luchtbal barracks just outside Antwerp. Here they started first with an appeal to unmask any 'wrong elements' among the military. Still accompanied by the Belgians, they travelled through the Scheldt tunnel to Hulst in the Netherlands in the evening, where they arrived exhausted around 2 a.m. Here they were housed in the Patronaatsgebouw.

In the meantime, a large number of Belgian and French soldiers had entered Zeeland (Belgium). Despite the Dutch capitulation on 14 May, they wanted to continue fighting with the help and side of the Allies. At the time of the capitulation, the Dutch troops in the province of Zeeland had been kept out of the surrender, because there were still foreign troops in this area. Rear admiral Van der Stadt, who had meanwhile taken over command, decided on 17 May to surrender Zeeland after consultation with the French army command. He ordered the Royal Netherlands Marechaussee to leave Zeeland to guard an airfield near Nantes. According to reports, aircraft and personnel of the Dutch Military Aviation had gone here. As far as can be ascertained, Daan was at that time with a few colleagues in Sluis or just outside it in a monastery in St. Anna ter Muiden.

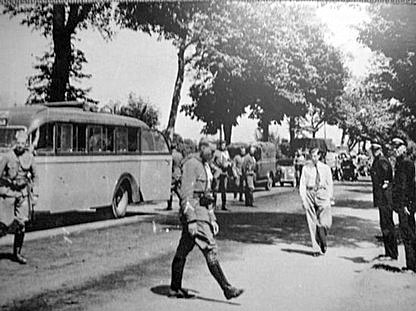

The command of the Marechaussee immediately requisitioned buses from the Zeeuwsch-Vlaamse Tram Maatschappij and other private bus companies with their civilian drivers. On May 18, this colorful column marched with the Police troops and other military personnel via Bruges, Ypres, La Panne and Dunkirk to Gravelines, where they finally spent the night in casemates on the straw. The retreating soldiers were hampered along the way by refugee flows and plagued by German air raids.

Daan said:

'We arrived at Abbeville in Northern France on May 20 and a bustle and a misery and a horror ... there those planes came again. I will never forget! I jumped into a dry ditch with my comrade, you believe it or not, in the middle of a bunch of nuns! We were there and those Germans fired a machine gun through that ditch. I don't know yet how we got out.'

He continued his memories: "We cycled with a large number of Marechaussees through the hilly landscape in Northern France. The elderly had a hard time with it and sometimes couldn't keep up with the pace. The young people often allowed themselves to be pulled by military and civilian motor vehicles. The following incident took place near Rouan: Barendje Uiterwijk, my buddy in Valkenswaard, got a flat tire and in panic stopped a bus full of Dutch officers. He asked if he could drive. The 'gentlemen' in the bus shouted to the driver: "Doooooooorrive!". Barendje shouted at the ready with his carbine: "I will shoot your heads off if I am not allowed to come along!" Nice that he could come along. " Via Rouen, it went towards Rouen, where they spent the night in cars and in the grass. On May 21, continue to Evreux, where most of the night is spent in the straw of a riding stable. Then via Les Mans to Angers where the men were welcomed in a Genie barracks. Food: soup, macaroni, steak and lots of wine!.

On May 24, just before Nantes, they were told that the airport was no longer required to be guarded. They traveled on to Vertou, where they spent the night in schools. On May 27, Daan and his colleagues received a message to come to a meeting point in Douvres-La Délivrande, a village north of Caen. All Dutch soldiers in France were expected there. After passing beautiful hilly landscapes in the evening we reached Laval, where they slept in a dirty barracks. The soup that was provided had an indescribable taste.

They arrived in Caen around 1 pm. Upon arrival, it turned out that this group was not the only one. There were six buses, a few large trucks with a platform above the cab, a semi-trailer with large numbers of bicycles on it, a few 5-ton trucks and dozens of passenger cars, almost all of which were from Zeeland, given their K registration. There were large numbers of Marechaussees who stood out for their beautiful blue uniforms ('the blues'). Here it was made clear that the ultimate goal would be England and that they were waiting for transport. They were assigned temporary accommodation near the old castle La Baronnie in Douvres-La Délivrande. Daan stayed in the open air on an elevated area behind the church in an apple orchard. Others were more fortunate and were housed in a school building in Cresserons.

Van de Velde visited here several times the religious services in the church "La Temple Protestant", led by his colleague Chief Guard-Brigade Commander A. Meulenberg from the district of Valkenswaard. He also spent time swimming and taking English lessons, among other things.

Division commander Den Beer Poortugael was meanwhile very busy organizing the crossing to England. Initially they were supposed to leave Cherbourg, but that eventually fell through. It later turned out that the ship in question, De Pavon, had undergone a heavy air raid. There were more than 600 victims, including many Dutch soldiers from the Peel-Raamstelling.

The crossing to England

The days in Cresserons passed quickly and on Sunday morning, June 9, it was time for them to start their journey again. The destination was Brest. The large French war port in the west was reached in the course of Monday, June 10. Almost immediately they drove onto the pier in the 'Port Commercial'. Several hundred Dutch soldiers were already here with their vehicles, who in a similar way had withdrawn from the grip of the Germans. In the middle of the quay was a large building with enough space for parking on either side. To this lay the light gray Ms. 'Princess Beatrix', from the Zeeland company, with the bow forward. It had arrived shortly before and had unloaded French soldiers who had taken part in the expedition to Narvik, which had not ended well.

The quay cranes immediately started to load the dozens of passenger cars and motorcycles with nets. It soon became apparent that there was no more room for the buses and trucks. The drivers were given the choice of staying behind with their vehicles or simply driving away or putting their vehicles away and boarding as passengers.On board they were served a hot meal, but had to go up and down three decks to get the food from the galley.

At about ten o'clock on the evening of June 10, the ship took off and slowly headed for the Channel. They were given very strict orders not to make any light whatsoever. One of the officers made particular efforts to make that clear. He threatened some with shooting if this order was not followed. These 'passengers' in Brest made up the majority of the troops arriving in England. On 11 June 43 officers and 830 non-commissioned officers and men arrived in Plymouth with the MS 'Princess Beatrix'. After the boat was ashore, no one was allowed to leave the ship. Three more meals had to be consumed on board and it was not until 9 pm that the train with an unknown destination was boarded. They stopped in Exeter around noon, where everyone was treated to sandwiches and raisin buns. They drove through the night and at 6:30 am the next morning they reached the station at Porthcawl in South Wales. Here Lieutenant-Colonel Noothoven van Goor welcomed the first exhausted and polluted men to a dark station.

Daan said:

"We marched early in the morning to the tented camp 'Dan-Y-Graig' (= under the rocks), which was situated on a sloping site with a view of the Bristol Channel. Here and there we saw residents looking at us from behind, pushed aside curtains. Later we learned that some had thought we were Germans. Our black shoes and leggings, along with the breeches we wore, contributed to this. '

This camp was already prepared due to the work of Lieutenant Colonel Noothoven van Goor who was already present in England. A total of 120 officers, 360 non-commissioned officers, 980 corporals and soldiers arrived in May and June of 1940. They came from the infantry, cyclists' corps, cavalry, artillery, engineers, aviation division, police troops and military police. They were the impetus for a Dutch armed force in Great Britain. Command of the troops here was in the hands of Major Sas. The command of the Marechaussees was in the hands of Den Beer Poortugael.

On August 16, 1940, a "mobile company" was formed from the Marechaussee who were under 38 years of age. Daan was one of them too. This company consisted of four platoons, each led by a chief guard. Captain E. Suijlen was in command. A police department was formed from personnel over the age of 38, under the command of Captain F. van der Kroon. This 77 man was given a precisely defined police task, such as supervision and control of Dutch soldiers.

The tent camp was surrounded by barbed wire. The "bunch of irregulars" was viewed with suspicion by the British in the beginning. They thought they were strange guys. On their arrival, and for some time afterwards, the camp was guarded by British soldiers and they were treated more or less, if not always in a friendly manner, as prisoners of war. Very understandable, because in the infamous May days the Germans had a hand in shoving a few cops and spies between the retreating and fleeing soldiers. Some of them have been removed from the camp and convicted. Moreover, the morale of the men was, of course, affected. The rapid German advance had made a great impression on them, while the separation of family and other relatives was difficult for many. The Dutch refugees also had to undergo an extensive British and Dutch security investigation. It is not surprising that the English were happy with the arrival of the Marechaussees and police troops, so that they could hand over the security with confidence. The guard was accommodated in a bus at the entrance of the camp. The police department had to take corrective action every now and then, as they had previously done in the Netherlands. All this did not always make them popular in the eyes of the military. The popularity of the guards continued to decline as they, as professional soldiers, were paid higher than the others.

Initially the name of these irregular troops in Porthcawl was: 'Detachment of the Royal Dutch Troops in Great Britain'. This name was soon changed to 'Nederlandsch Legioen', because the English used the term Foreign Legions for foreign troops in their country. Daan: "The population was nice. When they asked us: "Are you Dutch?" we said: "No, Dutch! "Dutch" also sounded so German ."

As the year drew to a close, the nights grew colder. Since the tent camp was not suitable for wintering, a suitable accommodation was sought. On September 28, a farewell evening was held at Coney Beach in Porthcawl, which consisted of music and singing. The highlight of this evening was singing the Legion Song with all your heart. On October 2, 1940, the men slept under canvas for the 113th time. When the tents were ironed, they left a clean camp. Two trains were waiting at the station in Porthcawl to take them to Congleton. They were waved goodbye by many English girls!

The Princess Irene Brigade is taking shape

A few hours later they arrived at the station in Congleton (Cheshire), a place which then had about 12,000 inhabitants. The Irene band was already waiting for them. They played marches such as 'Piet Hein'. Behind this corps they marched into town, with great interest from the local population. Part of it was stationed in the middle of the city in an 'uninviting, shabby, ragged, dilapidated' empty paper factory Park Mill. Better known locally as the area near the Fairground. Another section found shelter in the Riverside Mill and a group ended up in Buglawton, just north-east, in the Eaton Bank Mill.

Finally, the P.A.M. (Police Department Marechaussee), to which Daan also belonged, separately stationed in the Vale Mill. Good contacts with the local population compensated for many of the inconveniences. Congleton had a lot of industry, including textile, milk and cigarette factories. It also had a Village-Hall (for the 'dances'), two cinemas, ten churches and a cattle market. So it was an average English industrial town.

At the end of 1940, the government decided to form a brigade. It was named “Koninklijke Nederlandsche Brigade” and was founded in Congleton on January 11, 1941. Both the Queen and Prince Bernhard indicated that they could agree with the word "Koninklijke", but for eand further addition of a Royal name should show the Brigade even better skill first.

For the time being, the Dutch brigade consisted of a staff and two battalions according to British military standards. The 1st battalion, led by Major Doorman, was formed from the existing 1st battalion. The 2nd battalion, led by Major De Broeckert, was formed from the depot battalion and the company of mobile marechaussees. The reorganization would be effective January 1. At the time it was still the intention to form a complete brigade with three battalions and an armored reconnaissance division. The squadron of armored cars was to form the core of the reconnaissance unit, which was realized at the end of January 1941. A large part of the company of mobile marechaussees, including Daan, was assigned to this. Led initially by Captain Kist, then by Colonel Phaff, the later commander of the Brigade.

On December 30, 1940, the Compagnie Mobile Marechaussee, which had been established on September 24, was thus relocated from Congleton to Haughton, 5 miles southwest of Stafford. They were stationed there at Ranton Abbey Castle, which was owned by Lord Lichfield. The large building had 40 rooms and had its own power supply housed in the nearby tower. Since it was not visible from the main road, a sign was placed at the beginning of the driveway with the inscription "To Marechaussee". On January 2, 1941, the company's sixteen armored vehicles arrived. Company commander Capt. Kist liked field exercises. There were heavy multi-day exercises on a regular basis, usually in conjunction with the Home Guard.

At the time, Daan often went out with his colleagues in nearby Stafford. His later wife Doreen Lewis tells how they got to know each other: "Via the pub 'Bear Inn' in nearby Stafford, where many marechaussees of Ranton Abbey went out, Daan came at the invitation of my colleague as a guest at the staff evening of my firm English Electric in the Borough Hall. He looked very imposing in that beautiful blue uniform and besides that he was very charming. He asked me to dance and we had a date that week. That same week I introduced him to my parents and grandmother and they loved him, just like me. We were engaged a few months later and were married on February 21, 1942 in our village of Walton-on-the-Hill. "

On March 6, 1941, almost the entire Mobile Marechaussee company left Ranton Abbey for a two-day exercise. Some stayed behind for watch duties.

That same night, Ranton Abbey was destroyed by fire, probably by a flame-caught wooden beam running through a chimney. The fire spread very quickly. The room walls were made of wood and reed, held together by a layer of lime. Zane lost many of his personal belongings in the fire. The company returned to Congleton and was disbanded immediately. In September 1940, by order of the Dutch government, the construction of a camp for the Dutch troops in Wrottesley Park, 8 km west of Wolverhampton, had begun.

On July 10, 1941, Daan arrived in this camp with the rest of the Dutch Brigade. Wolverhampton was then a city of 160,000 inhabitants and a center of, among other things, the iron industry and machine factories. The camp covered an area of 150 ha. and was on Lord Wrottesley's estate, near Cranmore Lodge Farm. The Dutch in England were never allowed to name this camp for fear of spies. The stationed military spoke of Wolverhampton and the locals spoke of The Dutch Camp at Cranmore Lodge or the owner York's farm. The more than 100 new barracks, offices, dining and washing facilities, sports halls (unique at the time!), Tennis courts, theater and dining rooms were a relief. Electricity and running water were a luxury at the time. In principle, the designers had forgotten to build a gymnasium and rooms for religious practices, as well as an exercise area. However, these blunders were soon rectified. The camp was one of the most expensive in England at the time. Because the park was located eight kilometers outside the city, contact with the population was less intensive than in Congleton. Relaxation in the camp was sufficiently provided. Nevertheless, the back (Perton Lane) of this camp was often used by soldiers who wanted to take advantage of the nightlife in Bridgenorth (lots of attractive pubs!). It was namely close to a major main road.

On August 26, 1941, Queen Wilhelmina and Prince Bernhard granted permission by Royal Decree to the Royal Netherlands Brigade to bear the honorary name 'Princess Irene' from 27 August. The intention to form a complete Brigade of 3,000 to 5,000 men could not be carried out, because sufficient personnel was not available. The strength of men in April 1942 was around 1.300 men. The brigade's strength was weakened by the dispatch of detachments, the training of special forces and the designation of personnel for other destinations.

The Brigade in training

Because the Brigade could not be used as a combat unit due to its limited size, it became less interesting for the Allied troops. However, the government wanted a recognizable Dutch unity between the allied armies. On December 16, the Minister of War informed the Brigade that a reorganization was decided on January 1, 1943. For Daan, that meant the squadron of armored cars to which he belonged was disbanded. This unit consisted largely of enthusiastic Marechaussees. The atmosphere was great and many exercises were held that often stretched over great distances. The shooting practice in the mountainous landscape of Wales was popular. Sight seeing was also regularly done and that combination was very much appreciated by the men. In addition, the men of this squadron of armored cars wore a black beret, different from the traditional khaki colored beret.

The disbandment resulted in a large part of the Marechaussees being divided among the three battle groups. They came under the command of young military policemen, "the White", who were quickly promoted. The morale suffered so much from all this that after the farewell parade the entire squadron passed through the camp and hit the steel vehicles with hammers, causing enormous noise. Zane recalled: "That noise was a show of mourning, everyone was devastated that the squadron was disbanded."

The squadron did disappear, but the Brigade was indeed motorized. That meant that all three battle groups were equipped with 22 Bren and Loyd carriers, while the reconnaissance division (Reconnaissance Unit, called Recce for short) was equipped with modern Daimler (the "Dingo") reconnaissance vehicles.

In mid-May 1943, Daan's reconnaissance division went on exercise at Morecambe near Lancaster, 40 km north of Blackpool. The 80th Recce Regiment was stationed here in a holiday camp. This was a continued training of English soldiers and contributed to increase the skills of the Dutch. The cooperation with the English was fine. Although people did look up to the weekly compulsory Cross Country run, an 8 km long hike through hilly countryside. There was also a lot of target practice on the beach, where concrete posts served as the target for the anti-tank guns.

Under the command of Captain Looringh van Beek, the Brigade (without the artillery) left on June 12, 1943 for Ashridge Camp between Dunstable and Berkhamsted, in the middle of the woods. They were assigned here to the 61st Division Reconnaissance Unit. This camp, the size of a few square kilometers, belonged to Lord Rothschild, who, however, did not reside on this site. Dozens of tents were set up in the pouring rain. Each unit had its own tents and forest area. The tents included a number of small round eight-person tents with one tent pole and a number of large elongated tents with several poles in the middle and room for a double row of sleeping places. The two other battle groups were later also stationed in this camp. Numerous English soldiers were also present in this park. For the first time, exercises took place in a brigade, which had never happened before.

In the course of 1943 the XXI Army Group was formed under General Montgomery, which had been separated from the so-called Home Forces (British Territorial Troops). It consisted of the 1st Canadian Army and the 2nd British Army and was destined for the invasion of the European mainland.

In July 1943 the Irene Brigade was assigned to the invasion army. The Brigade was assigned defensive tasks and was moved to the coast on 29 September 1943 and was part of the Harwich Defenses, which also included parts of the Home Guard. Successively she was charged with coastal surveillance in Dovercourt until January 2, 1944, then in Frinton on Sea until April 10, 1944 and then returned to Dovercourt until July 29, 1944. All this was necessary to enable the Brigade to make landings. to practise.

The Waterfront in Dovercourt was actually the main neighborhood. The empty houses on this boulevard served as housing for the military and. The stoves were fired with coal and wood washed ashore. A Nissen hut at 15 minutes walking distance served as a dining room. On the beach was a wooden pavilion with veranda: 'Phoenix'. This was rented by the Brigade as a relaxation area for the troops. Once every fourteen days a 'dance' was organized.

It was known that General Montgomery would visit all parts that would take part in the invasion. On March 11, 1944, General Montgomery honored the men of the Princess Irene Brigade at the sports field in Frinton with a visit. He would inspect and address the brigade. All carriers and armored cars had been given an extra cleaning and the crews' couples and copper work were also shining in the sun. The Brigade was lined up in a u-shape and he climbed on a jeep and shouted: 'Break ranks!'. (break the ranks!) He gave a speech reminding the Brigade of its expulsion of the Germans from North Africa and that it was now Europe's turn. 'We will bomb them!' He also warned the Irene men that the Germans were good soldiers, but that the Allied soldier is much better.

On May 11, all private property belonging to all soldiers was packed in boxes and suitcases to be stored in WrottesLeij Park. As of May 20, travel was banned from outside a 25-mile radius from Dovercourt station. A brigade order of May 27 stipulated that every soldier was obliged to be vaccinated against certain diseases. Also, 24-hour leave could no longer be granted.

In the early morning of June 6, all of the Brigade's soldiers were awakened by the sound of thunderous aircraft engines and violent cannon roar. Hundreds of planes flew in a southeasterly direction. It was clear that the big moment had arrived and the invasion had begun: D-Day!

A few more weeks passed with waiting, practicing, and waiting again. On the twenty-ninth of June 1944, to the astonishment of all and the disappointment of most, the order to move from Dovercourt to Narford-Camp, near Narborough (near Kings-Lynn), was issued. Exercises in a larger context took place here, including with the Belgian Brigade Piron. There was hardly any food in this camp and no drinking water at all. There were also no plates, so that people already had to use the food games (mess-tins). It was the first little hardships. Dutch humor also came into play: many tents were given a painted name such as "Stalin Inn", "Never thought" and "Chairborn troops" were muddled on the staff tent at night. In the Village-Hall (community center) in Narborough, a film was shown by the English army showing how to defuse German and Italian mines. It was a compulsory film visit that was followed with great attention by all those present. The old weapons and equipment were handed in and new brencarriers, weapons and equipment were received. The men were given new uniforms and shoes. The coupling straps and cartridge bags were now suddenly no longer allowed to shine, but had to be made dull.

The Brigade is going to the front

On August 1, 1944, weeks after the successful invasion, the coveted order of departure finally arrived. It contained precise details of what could be taken, what should be loaded onto the wagons and how packed. By 5:30 p.m. on August 3, 1944, an eighteen-kilometer column left Narford camp at Narborough for the 300 km distant Wanstead Camp at Leightonstone, near London in the so-called 'Marchalling area'. collected for the crossing). The site was the size of a football field. The shelters were again a few large tents. Mattresses and blankets were lacking. No one was allowed outside in this camp and was therefore cut off from the outside world. Letters were not to be received or sent. The camp was closed off by barbed wire meters high and meters deep. In addition to a swimming belt (jokingly called "Mae West"), Daan also received 24-hour rations and French money. In addition, everyone received fifty sharp cartridges for their weapon; it got serious.

On the evening of 5 August at 7:00 pm they, together with the Belgian Brigade, headed for the coast of Normandy under the protection of warships. A German plane flew over high and dropped some bombs haphazardly, which did no damage. After a crossing in beautiful weather they arrived at the French coast on 7 August at 7 pm. Zane's brigade headquarters, artillery battery and reconnaissance division were embarked on the Liberty ship Samvern early in the morning of August 4. At night the ship joined a convoy near the Southend rally point, and on the evening of August 5 the ships set off on a mirror-smooth sea. On August 6 around 5 p.m.

the ships arrived at the French coast. Hundreds of ships were bobbing there, while strangely enough, there was no sign of any activity. The brigade headquarters, reconnaissance division and artillery battery were not disembarked for unknown reasons until August 7 and went ashore on the beach at Graye-sur-Mer.

That same evening, the Brigade left for the reception camp at Cresserons, 4 km from the coast and 15 km north of Caen. On their way there they passed Douvres with the nearby hamlet of La Delivrande, which housed a Dutch detachment from May 28 to June 9, 1940, before leaving for England. Until further notice, the Brigade was housed here in a forest complex. Daan could not sleep that night, because of cannon roar and machine gun rattle in the surrounding area. He attended a church service for the first time on the mainland the next morning. This turned out to be in the same church where he and his colleagues had attended a service in May 1940.

The following day the Brigade was assigned to the 6th Airborne Division, commanded by General Gale. The men camped between Plumetot and Cresserons in previously explored orchards, meadows and forest edges. They were given four days to get everything in order. Checking the equipment was a priority. Ceaselessly, Zane heard the roar of the heavy guns fired 40 km away. They stayed here until August 12. Then the Brigade moved to the Orne Front, where the 6th Airborne Division had set up a defense against the Germans. Together with the Belgian First Brigade 'Piron', the Princess Irene Brigade reinforced the parachute division, which had been in continuous action since 6 June.

The Brigade was ordered to proceed to Hell Fire Corner early in the morning via the famous so-called Pegasus Bridge. This sector was so called because the British and Canadians had been under continuous fire from German panzer divisions and SS troops here from the very beginning.

The area where she provisionally camped was a triangular orchard with adjoining pastures that were under water from the River Dives. In the still water was a lot of rotting fruit and the carcasses of dozens of horses. As a result, it attracted many mosquitoes and wasps that caused a lot of nuisance. Daan: "I soaked the camouflage net of my helmet in the petrol to keep the mosquitoes at bay. It made you distraught ".

The Brigade here relieved the Royal Ulster Rifles and a company of the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. These men were completely exhausted after two months of fighting. The Dutch headquarters was housed in a badly damaged house, behind the ruined castle Chateau St.Côme, less than a kilometer from the three battle groups. Just before the arrival there were large signs along the road with the inscription: "You are now in full view of the enemy". German troops of the 744. Infantry Regiment were indeed about 250 meters away. The task of the Brigade was to keep the Germans here, while other Allied troops made a circling movement around the city of Caen.

Daan later said:

"The castle also had a stud farm" Les Haras de Bréville, where dozens of dead horses were scattered around. Quicklime had been thrown, but that had not been enough to stop the rotting of the cadavers. Due to the dangers of the front, there had not yet been an opportunity to clean up the stinking remains. The August heat worsened the situation and there was a scent of corpses around the positions that made troops gag ".

The site, the famous Norman "bocage", consisted of small patches of pasture or orchard separated by dense groves on a high wall. It was perilous to stay above ground during the day. The soldiers therefore took possession of the foxholes dug by the Germans in the ramparts around the meadows. In an orchard near the Dutch positions was a temporary mass grave, on which empty bottles had been placed containing notes with the names of the fallen. The graves of the English and Germans were next to each other.

The Irene men had no war experience and were baptized by fire. It was by no means a quiet place. This place was nicknamed 'Hell-Fire-corner' for good reason. Around nine o'clock in the evening a fierce artillery fire suddenly broke out and lasted quite a long time. The bottles on the various graves flew to shards. Several men were so surprised that they could no longer reach their foxholes.

By evening on August 14, the positions and brigade headquarters were again under heavy fire from both German artillery and mortars. The forest around the headquarters played into the hands of the Germans: the shells jumped into the trees and a huge shower of shrapnel descended on Irenemannen. Guardian Lammers of the medical service, while reading a letter under a tree, was fatally hit by one of those shards and was the first person killed in the Brigade. In England he had been under-bandmaster of the Princess Irene band and composed the Brigadier song, the current Irenemars.

Life at the front was not easy. Zane recalled, “There was very little to eat and we had a vitamin deficiency and symptoms of scurvy. We ate overgrown lettuce plants and wild sorrel and even cooked grass. ' On August 15, Daan's reconnaissance division was hit by an attack of dysentery. The tea, with tainted milk powder in it, was probably the main culprit. Daan sought the cause more in the overrepresented flies of a nearby cemetery of the dead. Thirty persons of the Scout Troop were in very bad shape and were put in a hospital in La Delivrande. Some of them floated on the verge of death for days. Others 'lay like a dead body' in the orchard. Fortunately, the unfortunate people recovered with rest and better food.

Daan:

'There was a complete war in my intestinal system. For days I produced a mixture of blood and mucus and felt as sick as I had never been in my life. ' Meanwhile, Zane was crazy about the eternal bagpipe music of the English: "We even made plans to kill that bagpipe player."

On August 20, 1944, the order to leave finally came, 'Prepare to Move': Battle Group I took over the bridges at Varaville, Battle Group III the town of Petitville, while Battle Group II still stayed at Quistreham. Daan's dysentery-weakened reconnaissance unit did not participate in action. The headquarters had been set up in the badly damaged Chateau Benauville, where the Germans had smashed the furniture and scattered the books from the library on the floors.

In the meantime, the German troops were surrounded by the Allied Expeditionary Force on 20 August 1944 in the so-called 'Pocket of Falaise'. Some 10,000 Germans had been killed, while 50,000 were taken prisoner of war. The German 7th Army was crushed and the meager remnants of the army, which the Allies had to throw back into the sea, fled headlong northwards.

The Allies rush to chase the German troops on their way back to the Seine. The Irene Brigade, still under direct command of the 6th Airborne Division, pushed the fleeing Germans north along the coast to the Seine at Le Havre. The task of the Brigade was to follow the enemy closely so as not to give the enemy a moment's rest. The rest of the division would then move south of the River Dives, cross it and attack the enemy from behind.

"The push-through to Pont L'Evèque. There we shared a pit to sleep with two men. Then you could lie comfortably under two blankets. I hadn't dug a hole myself, but found one. Nice and easy! We turned out to be in a German latrine. Stink the next morning! But luckily there were plenty of supplies, so we were able to swap the stuff, "said Daan.

The Irene Brigade had been ordered to move via Dozulé and Annebault to a place southwest of Pont L'Evèque, to camp there for two days. During the bivouac on 23 August, Prince Bernhard, together with his adjutant Baron van Tuyl van Serooskerken, paid a visit to the reconnaissance unit and GGI and III of the Brigade. He conveyed the best wishes of Queen Wilhelmina and showed great interest in the moral condition of the men. He even listened comfortably in Daan's command car to the B.B.C. news.

On August 24, it was reported that the Irene Brigade was under command of the British 5th Parachute Brigade, after which the Brigade headed towards Pont L'Evèque, some 25 km away, early in the evening. Here some bridges had been blown up, so that the heavier equipment was temporarily left behind. The distance was therefore partly covered on foot. After the bridges were repaired in the evening, the Brigade advanced to Vieux Bourg and Les Anthieux. There was hardly any opposition from the Germans. It was intended that St. Benoit and Beuzeville should have been captured by August 26, but the commander of the 6th Airborne Division, General Gale, decided to take a swift action one step further and capture Pont Audemer. In this way he wanted to cut off the retreat of the Germans south of the river Risle. How the general imagined this was crystal clear: the order was; "You must get there as quick as lightning!", (Like lightning so fast!).

The city of Pont Audemer was the key point in the coastal region, because in that city was the and ige intact bridge, over which the Germans could escape. The bridge was of strategic importance. The general was of the opinion that it would be a feat to take control of that bridge and also the city. The problem was that the city was not in the allotted sector of the 6th Airborne Division. By order of the authorities, the city was destined to be liberated by the 49th Westriding (Polar Bear) Division. However, the 49th Division was still a long way off and was still south of Dozulé in the early morning of 27 August. This coincidental circumstance made General Gale see his chance. In consultation with the commander of the 5th Parachute Brigade and the commander of the Princess Irene Brigade, the Brigade was ordered to go "lightning fast" to Pont Audemer, take the city and get the bridge in its entirety. Because the trucks of the infantry were on loan, the reconnaissance division of the Belgian brigade Piron was ordered to bring the infantry of battle group I to Pont Audemer. A squadron of tanks was placed under command, on which the infantry of Battle Group III could ride.

When the built-up area of Pont Audemer was reached, the Belgian reconnaissance vehicles stopped and a total of three platoons of Battle Group I were deposited. The men of Battle Group I continued on foot, followed by the tanks. Upon arrival, it turned out that the Germans had already blown up the bridge and evacuated the city. After a few skirmishes with a small rearguard, the city fell into the hands of the Dutch. There were only a few civilians in the city and a warm welcome with flowers or calvados was out of the question at the time. Laconically reported the war diary; "After some gunfire, the Brigade occupied their first French city around 9:00 am."

On August 29, the Irene Brigade moved to Colletot, just east of Port Audemer. The brigade was charged with guarding the river and clearing the south bank. Since not a single bridge over the Seine was intact, scattered German soldiers attempted to reach the river on their own initiative by various routes. In the many bends of the winding Seine were numerous German troops, trying to get to safety with everything that could sail.

The Irene Brigade was charged with guarding the Seine until August 30, 1944. The situation on the north bank of the river also had to be investigated. This and the following day, the first of the Allied troops to send out patrols across the river. Volunteers, mostly ex-legionnaires from the French Foreign Legion, who had good knowledge of the French language, made themselves useful and crossed at night at Vieux Port de Seine. They explored the terrain and also made contact with the French underground, the 'Maquis', to learn about the positions of the Germans.

The Brigade is deployed to liberate the Netherlands

The Brigade, which until then had served under the command of the 6th Airborne Division, was redeployed for the next phase of the advance. Together with the British 49th Division, Canadian 3rd and 2nd Divisions they were assigned to the 2nd Canadian Army Corps. On September 2, the Brigade was ordered across the Seine and marched towards Le Havre.

Hidden from the men at the front, there were all kinds of developments at a high level regarding the fate of the Brigade. The commander of the Brigade, Colonel Ruyter van Steveninck, wanted the Irene Brigade to be the first to set foot on home soil and therefore submitted the request on 4 September to be assigned to the 2nd British Army. This army was earmarked to liberate the Netherlands. The request was supported by Prince Bernhard, who had recently been appointed "Commander of the Netherlands Armed Forces", as well as Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government. British politicians were not reluctant to this request and partly because the Brigade had proven itself as a well-trained unit, the request was granted.

The result was the order to go to Diest, which is 300 km away, in Belgium. There the Brigade was assigned under the command of the Guards Armored Division. In the meantime, parts of this division and the rest of the 30th Army Corps, including the Belgian Brigade led by Colonel Piron, had already reached Brussels.

That same evening at 9 p.m. the Brigade left for Airaines, where it arrived just after midnight. Then came the order to move the Brigade, under the command of the 30th Army Corps, immediately via Amiens, Doullens, Arras, Douai, Tournai, to St. Pieters Leeuw, just below Brussels. In the morning on September 6 they crossed the border at Belgium and at 10.30 am they arrived at their destination after a lightning fast 270 km ride. Here Irenemannen met crew members of English armored cars who proudly said that during a reconnaissance briefly crossed the Dutch border.

Near Brussels. in St. Pieters Leeuw, the Brigade was placed under the operational command of the 30th Army Corps. The order soon followed to march to Beringen to support the Guards Armored Division. After a break of several hours, they arrived in Brussels in the afternoon. It was an unforgettable journey. Hordes of people brought in the Brigade as liberators. It was a tightly packed, waving, cheering crowd. Even at low speed it was not possible to continue driving. The vehicles were forced to a stop by the crowd.

Daan recalled: "In Brussels it was a huge party atmosphere with flags everywhere. Trays of tomatoes and fruit were thrown at us. In Leuven it was even worse. We could hardly get through the throngs of people there. "

The Brigade had to go via Leuven to Diest and then via the Staatsbaan to Beringen on the Albert Canal. In Leuven, too, there was no way around it: garlands of flowers, drink, singing and women fell to the brigade men. From Leuven the road to Diest crossed the village of St. Joris-Winge. The Irene men drove in a victory rush, singing in their flower-decorated armored cars and reconnaissance cars, heading north. The reconnaissance unit kicked off, followed by battle group III, brigade staff, battle groups I and II, artillery battery and brigade companies.

On the way, members of the Belgian resistance ('the White Brigade') had already warned the brigade staff that there were still Germans active in the area. Large parts of southern Belgium were liberated, but here and there German units and snipers were still active. The order was given to increase the distance between the vehicles from 50 to 100 meters. In a very good mood, some 'partygoers' ignored this order. As the column moved on a narrow road just before the village of St. Joris-Winge, it suddenly stopped at the front. This caused the vehicles of Battle Group III to collapse, because the Reconnaissance Group did not have a sufficient lead. Unexpectedly, the front battlegroup was fired on from the front and from the right with cannons and machine guns. Some Tiger tanks stood about 600 meters sideways at a farm covered by bushes.

At the reconnaissance department, the front car was fired upon by a tank, where the machine gun gunner Henk de Groot was killed instantly. Daan and his other colleagues jumped out of the cars and took cover in the dry ditches. Very soon explosions followed and plumes of smoke rose above the column. In the chaos that ensued, the platoon commanders did not know where their people were and there was no effective command. In the meantime, the Germans bombarded the column with cardboard shells. This type of grenade sprayed a shower of small pellets over the men, causing many injuries. The chaos was complete!

Battle Group II deployed the anti-tank guns in no time. British tanks also came to the rescue. When the fire died down, the German tanks were found to be out of action or driven out. After a delay of two hours, the Brigade reached the town of Schaffen, near Diest and the Albert Canal, late in the evening. After a short night's rest, the following morning, 7 September, they continued towards Beringen.

Almost all bridges over the Albert Canal had been destroyed by the Germans and they reinforced their defense line on the north bank with Waffen-SS troops (Dutch volunteers from the "Landstorm Nederland" division!) And paratroopers. Reconnaissance along the canal showed that the bridge at Beringen had not been completely destroyed, so that the same morning infantrymen established a bridgehead under cover fire from the Guards Armored Division and engineers built a Bailey bridge.

Three in the morning the first tanks rolled into Beringen. They arrived just in time. On September 8 there were still many German troops in the vicinity of this temporary bridge. At daybreak they bombarded the Allies incessantly and tried to penetrate to the edge of the town by counterattacking from the west. The population of Beringen located on the north side of the Albert Canal fled the cellars into or out of the city. The intention was to destroy the Bailey Bridge over the Albert Canal. Heavy fighting broke out and the attack was halted 200 meters from the bridge. The last chance the Germans had to capture the bridge had passed.

Shattered British tanks still blocked the way to the emergency bridge on 9 September. Because this bridge could not carry heavy equipment, the Allies were unable to dislodge the fanatical German defenders for the time being. A few hours before daybreak, a German battalion penetrated to the southern edge of Beverlo. The 8th Armored Brigade, arriving in the bridgehead in the evening and in unknown territory, was not ready to relieve the troops of the 32nd Armored Brigade. As a result of the darkness, the enemy was able to penetrate the brigade's lines.

In no time at all, 46 trucks loaded with gasoline and other supplies were ablaze, while moments later the forest in which they stood was burning like a torch. In the ghostly light of this blaze, the German attack was dispersed and driven back by concentrated fire from the Brigade battery and fire from British tanks. The same day, an armored brigade of the Guards Armored Division was the first to penetrate Beringen across the Bailey Bridge. Later that afternoon the three battle groups of the Irene Brigade, the artillery and the reconnaissance division also entered the badly damaged Beringen. Irene infantrymen chased the last of the opponents out of the houses. After this the enemy tried to infiltrate the Allied lines with small groups. The Brigade was able to expel the enemy for good and took 45 Germans prisoner. Battle group I was guarded at the emergency bridge, battle groups II and III were deployed east and north of Beringen. Daan's reconnaissance department took up positions in the coal area of Beringen-Mine. Here Daan took a lovely warm shower for the first time since the Normandy landings. The coal mine management had provided the miners' large washing and drying room for the Brigade, and all units took turns taking a hot shower.

After all these complications, Battle Group I was ordered to clear the forest in the direction of Leopoldsburg from Germans with the support of tanks. During this action, which lasted several days, dozens of prisoners of war were taken without losing a man. The resistance of the Germans was broken and the Allied High Command now wanted to advance quickly to the Netherlands. On September 10, Battle Group III of the Brigade was ordered to occupy Beverlo.

The first fights in the Netherlands

On September 16, the Staff of the Irenebrigade in Leopoldsburg was informed by commander of the 30th Army Corps General Horrocks that a major operation was planned to end the war in Western Europe: Operation Market-Garden. He said to his audience, "Something is going to happen that will make our grandchildren proud of us that we have experienced such an operation."

The operation consisted of airborne landings code-named "Market" and an overland advance code-named "Garden". Just before departure, the Brigade staff received a map of the Arnhem area with a scale of 1: 50,000, with the German positions printed in red on it. The Brigade also provided many interpreters for this operation, which earned it the nickname 'Brigade of guides'. On September 16, the Brigade came under command of the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division, which was to advance behind the Guards Armored Division. On September 18, the Brigade was moved two kilometers to the north of Helchteren and was warned to be ready for immediate departure. The men became impatient, especially when someone from the brigade staff returned from liberated Eindhoven. They still had to wait until September 20 in the afternoon, before the march was started towards the Dutch border. The reconnaissance unit led the way, followed by the marine unit and the other units behind.

Daan:

'It was a strange feeling to drive back into the Netherlands after all these years: a hoarse throat, not speaking for a while to find my voice again.'

The Brigade was assigned to the first troops to enter the Netherlands. At midnight from 20 to 21 September, the Irene Brigade passed the Dutch-Belgian border at Borkel and Schaft. Several Irene men got out of their vehicles and briefly felt the ground. Despite the bad weather that morning and the early hour, people from Brabant were everywhere cheering the liberators along the road.

We arrived in sleepy Eindhoven at 6.30 am. Via Son (9.00 am) to St. Oedenrode and then to Veghel and Uden, where the church bells were ringing. At 2 p.m. the vanguard reached Grave. A little later they marched to the assembly area in Lunen, a few km north of Grave, where the following day the Brigade was given the order to take over the security of the strategically important Maas bridge at Grave.

On September 24, the British engineers built a second (pontoon) bridge over the Maas at Grave, so that the Irene Brigade had to guard this bridge from September 26 as well. On September 25, the reconnaissance division carried out a patrol in the land of Maas and Waal. Eighteen NSBs were arrested during this trip.

On September 28, the Reconnaissance Department they take care of the northernmost part of the land of Maas and Waal with an observation post in a brick factory in Druten. The lookouts looked across the Waal to the northern bank occupied by the enemy. The post in Druten was only occupied during the day, at night they used a listening post a little further on in Deest.

On October 1 and 2, the reconnaissance department reported raids by the Germans in Wamel (opposite Tiel), in which civilians were captured and thirty houses were set on fire.

The reconnaissance unit was moved further from the river in its entirety to Horssen on 5 October, from where patrols continued. Daan lived here in a dry ditch and other colleagues in a somewhat more comfortable old church.

In the night of 6 to 7 October, the Germans extended their aggressive patrols on the liberated side of the river to Leeuwen. They arrived at the southern crossing of the Waal around 2 a.m. The patrol was professionally organized. While guards scanned the area for danger, the test began its destruction work. They threw fire bottles with green liquid (phosphorus) through the windows of the houses. The population was chased into the streets in night robes and 47 houses burned to the ground.

On the same night of October 7, two of Daan's direct colleagues, Marius Kroon and Raymond Arnoti, were killed when they were ambushed while patrolling the dike at Boven-Leeuwen. In the afternoon a solemn funeral took place at the Dutch Reformed cemetery in Horssen, where the inhabitants provided many flowers.

A friend of Daan said:

'At Boven-Leeuwen I had exchanged a guard with another soldier. I was just under my blanket when I heard: 'package package' and 'boom'. A German had fired on the guard and hit a grenade on his belt, which exploded. That was the watch I originally had to walk. I was really lucky '.

The situation near Arnhem and Nijmegen in early October 1944 was not as the army command had envisioned. Market-Garden had failed and large parts of North Brabant were still in German hands. The long and vulnerable supply lines and the insufficient capacity of the small ports on the Channel endangered the advance to the north. It was of immense importance to have a large port in this region. Antwerp was a logical choice for this, although the Germans had to be pushed back across the Maas and Hollands Diep first.

On October 22, the 12th Army Corps was to be deployed to take control of Antwerp. In anticipation of the major offensive, the Brigade, under command of the 4th Armored Brigade, was directed to the Eindhoven area on 13 October. On October 17 they arrived at the Oirschotse Heide and surroundings. The headquarters was located in Oerle, west of Eindhoven. It was very cold and damp here and the Germans continuously bombarded the positions with mortar fire. The assignment was to prevent them from crossing the Wilhelmina Canal from the north bank and to prevent them from taking offensive actions.

In the night of 22 to 23 October it suddenly became quiet and early in the afternoon the reason why became clear: "Suddenly, two civilians were waving a white flag. We kept our finger on the trigger. They told us that the Moffen had left Oirschot in haste. The English tanks rolled into the village and I heard the civilians cheering. Unfortunately we did not go in, although we would have liked to share in the joy ".

That same afternoon on October 23, the brigade commander was ordered to move the Brigade from the Oirschotse Heide via Zeelst, Oerle, the heavily damaged Middelbeers and Diessen towards Hilvarenbeek. The Brigade was commanded here by the 15th Scottish Infantry Division.

On October 24, the Brigade Commander was ordered to move the Brigade towards Tilburg. The spire was formed by the reconnaissance group. They were to kick off, followed by Battle Group II, followed by twenty English Sherman tanks, Battle Group I, then Battle Group III, the staff and finally a battalion of the London Yeomanry. The plan was to move forward in four phases, clearing roadblocks and clearing the forests along the road from Germans. The ultimate goal was Broekhoven to lay a foundation there for further operations. As a follow-up to the operation, a tank regiment was ready behind Hilvarenbeek to push through Tilburg.

On Wednesday 25 October at 7.30 am, the 46th Brigade of the 15th Scottish Division advanced from the direction of Oirschot to the east side of Tilburg. At the same time, battle group II of the Princess Irene Brigade left from the south, in the direction of Hilvarenbeek, a planned breakthrough forcing to Broekhoven.

The advance began with the three reconnaissance vehicles of the Brigade's reconnaissance division as its spearhead. These were the vehicles of watchmaster Geeraards, lieutenant Driebeek and lieutenant Van Voorst tot Vorst. They were supported by artillery, two tanks of the 4th Armored Brigade and three armored cars. After much talk on the radio, the Sherman tanks came forward. After the long wait, the front reconnaissance cars could also continue. Less than 200 meters further, 36 Germans appeared out of nowhere to surrender. This encouraged the men of the first reconnaissance vehicle to continue to the Leij. The stream turned out to be an obstacle because the bridge had been blown up.

The road from Tilburg to Hilvarenbeek first passes through open arable land known as De Voort and Grote Westerwijk, and then turns into a two kilometer long forest. On the way there the Irene men encountered many obstacles, such as blockades of farm wagons with booby traps, wire fences, trees on the road and craters in the road surface. Three consecutive skirmishes with Germans followed here. The first at De Westrik, then at Grote Westerwijk and then in the forest area that ended at the Oude and Nieuwe Leij. However, the accompanying tanks and artillery put the enemy to flight. At Liza's Hoeve, the Brigade encountered heavy artillery fire from the Germans, which set a British reconnaissance tank on fire.

The enemy fire was the reason for Lieutenant Driebeek to command the car of Geerards and Veerman back. The driver ignored the warning not to reverse fast. Due to too high a speed he suddenly had to swerve in front of the burning tank and ended up in a pond next to the road via a foxhole and flipped over. Lieutenant Driebeek and Lieutenant Van Voorst tot Voorst crept ten minutes later through a ditch to the crashed reconnaissance vehicle. Van Voorst pried the hatch loose with the key to his own car and Geerards, the watchmaster, crawled out. His driver Veerman had his head under water and had lost his pulse. It later turned out that he had broken his neck.

The Germans had set up a forward defense on the river Oude Leij and had good anti-tank weapons. The combination of the open firing field, the swampy terrain and the dreaded 88 mm anti-tank guns were sufficient reason to stop the advance. Nevertheless, battle group II (led by captain of the marines H. Arends) advanced towards the brook with the support of artillery and mortar fire. Yet they were also brought to a halt south of the Leij. Despite repeated attempts, it was not possible to cross the Leij. The center of gravity of the German defense was in and around a large factory complex of Verschuuren-Piron near Broekhoven. The complex was apparently not much affected by the English artillery fire as the defense remained intact despite fierce shelling.

Daan recalled the following episode at the Leij: 'We were in a ditch near that bridge and a German with a white handkerchief came towards us. Sergeant Buytelaar went to the man with some of his men and was ambushed. Some Germans were taken prisoner, but the sergeant had already bled to death. '

The reconnaissance vehicles were brought back to headquarters, but were plunged there by the enemy and then buried under a barrage of German artillery. Zane had already warned the command that they were in one place for too long and there was too much radio traffic. He took shelter under his car and was slightly injured by splinters, but he later said that he was near despair with fear. However, his mate Gerard Dijkstra was killed and many people were injured by this shelling. A few boys could not mentally cope with the shooting and were sent to Eindhoven in shock. Their eyes were skittish, they talked in fits and starts and could not keep their hands still. Battle Group I (led by Major Paessens) and Battle Group III were located to the left and right of the access road to Tilburg and were also under German fire continuously. So new plans had to be made to defeat the enemy. In the meantime it had already gotten dark, so they had to wait until the next day.

The commander of the 4th Tank Brigade decided to take things more vigorously. The attack was to be carried out the next morning with the two remaining battle groups of the Princess Irene Brigade, reinforced with tanks and supported by artillery. Battle Group III, supported by a squadron of tanks and an artillery division, was to carry out the attack on both sides of the road running from kilometer marker 30 on the Wilhelmina Canal to the Monastery. The attack was to start at 6:30 am on October 26.

The final orders did not reach the commanders until 6 a.m.. The commanders of the two tank squadrons, who were to support the attacks, were not present, so that the Dutch commanders of the two battle groups went out "on their own" to do a reconnaissance mission of the area.

The terrain was very swampy with lots of ditches. A dense fog hung over the ground. The battle group commanders insisted that the attack be postponed for some time, so that they could still carry out a reconnaissance with the tank commanders. But this request was denied. Battle Group III launched the attack first, followed shortly after by Battle Group II. At the start, Battle Group III encountered no resistance. The Leij was reached without a German reaction. When one of the leading platoons had already crossed the Leij, all hell broke loose. This platoon was attacked from all sides. It could not hold its own and had to go back. A second transition attempt also failed.

The Germans had the advantage of being able to shoot the Dutch with good effect from their well-camouflaged positions without direct sight. After all, they knew the places where the attackers would cross the water stream. The attackers, on the other hand, were completely in the dark about the location of the enemy weapons. As a result, well aimed fire could not be delivered with both artillery and hand weapons.

Battle Group III's attack had stalled. Battle Group II did not get much better. During the advance to the Leij she came across a German patrol. This was able to signal the approaching attack, because shortly after the contact the Germans concentrated their artillery and mortar fire on and along the road, which formed the attack axis of Battle Group II. All it took was to take cover in the deep ditches, holding on to barbed wire and branches of the trees by the side so that they would not drown. In spite of this, people went forward, although this was now of course happening at a slow pace. To make matters worse, the fog suddenly cleared, giving the German machine guns a chance to intervene in the battle. As visibility improved, the Germans opened fire with machine guns positioned flanking from the factory complex at Broekhoven. There was no further advancement under this intense anti-aircraft fire. To avoid heavier losses, the commander of the 4th tank brigade decided not to continue the attack. During the retreat, mortar shells fell between the soldiers, but they all smothered in the swampy ground. Mud columns were created, but fortunately the fragmentation effect was limited.

Daan recalled:

"Early in the morning we saw a man waving a white flag on the other side of the Oude Leij. He shouted to us that the Germans had left. "

During an encounter with a German patrol, a sergeant major was captured, who turned out to be in possession of a sketch showing all the German positions around Tilburg. The attackers now had a full understanding of the German positions. One of the captured Germans announced that the defenders would withdraw on the night of 26 to 27 October. Chances were they would otherwise be trapped in the city. The commander of the Irene Brigade, Colonel De Ruyter van Steveninck, understood that the Germans were going to evacuate Tilburg to avoid encirclement. He therefore urged a resumption of the attack. The commander of the 15th Scottish Division was not confident in this and decided to let stronger troops continue the attack.

In the morning of October 27 at 7:00 am, the 44th Infantry Brigade, preceded by a heavy artillery bombardment, crossed the front of the Irene Brigade with heavy tanks and at 5:00 pm Tilburg was in its hands. General Barber, the commander of the 15th Scottish Infantry Division, was honored as the liberator in Tilburg. With the exception of the Artillery, the Brigade was not allowed to enter Tilburg with the 44th Brigade. They were allowed to participate in the parade in honor of the liberation on November 4.

Deployment on the Maas front

In the afternoon at 5.20 pm the march started via Hilvarenbeek, Hoge- en Lage Mierde, Dutch-Belgian border, Aerendonk to Weelde. The reconnaissance unit was housed here in farms at 7:30 PM. The following morning, October 28, the journey went via Poppel, Goirle and Tilburg, where half an hour was held for contact with the population, towards Breda.

The Brigade was ordered to leave for Maasbrug, a gathering place west of Tilburg. Once there, the Brigade came under the command of the 7th Armored Division, the famous "Desert Rats". The Reconnaissance Department and the command post were placed just outside the village of Hulten.

On October 31, the Brigade was moved to Raamsdonkveer. Via Tilburg, where most soldiers first came into contact with the local population, and from Dongen, the Brigade arrived in Oosteind, west of 's Gravenmoer. Here, too, the reconnaissance division patrolled the river. No enemies were found during this period. On 1 November battle groups I and III also moved into positions at Waspik-Raamsdonkveer, from where patrols were sent to the Bergsche Maas to prevent infiltration attempts by the Germans in a southerly direction.

On November 4, the men who were not in the front line were sent to Tilburg, where a small parade was held, in which Prince Bernhard and the city council were present and the Irene Brigade was honored for its contribution to the liberation of Tilburg.

Between 5 and 11 November, the reconnaissance division of the Irene Brigade was placed near a drainage canal in Baardwijk. There were many minefields in this area, as a result of which some soldiers during a patrol along the Maas ran into a mine and were seriously injured. A good friend of Daan van de Velde, Mike van Lienden, was seriously injured by an exploding mine.

Meanwhile, Walcheren had fallen into the hands of the Allies and the first supply ships were preparing to call at the port of Antwerp. The Princess Irene Brigade was asked to perform surveillance duties here. For this task they were placed under the command of the 52nd (Lowland) Infantry Division. On November 11, the Brigade traveled to Wuustwezel in Belgium, to enjoy a well-deserved rest for a weekend. On 14, 15 and 16 November the Brigade left via Putte, the heavily damaged Hoogerheide, Woensdrecht, Goes and then on foot (!) From Arnemuiden to Veere in Zeeland. Upon arrival, Walcheren turned out to be mostly under water. The Allies had bombed the island's dikes, leaving the flood free in the polder landscape. The residents, insofar as they had not been evacuated, were crowded together in dry places. Part of the city in Middelburg was flooded and many buildings were destroyed. Vlissingen was also heavily damaged, as were many towns in South Beveland.

The front line ran along the banks of the Oosterschelde, the Mastgat, Volkerak via the Hollands Diep and further along the Maas. Due to the great importance of the port of Antwerp for the logistical situation of the Allied Expeditionary Force, the defense of this front was very important. For the Germans, Schouwen-Duiveland was the closest base for attacks on the Scheldt. The opponents were committed to observing each other's positions, activities and intentions.

Daan was deployed with his reconnaissance unit in North Beveland. They were commanded by 52nd Reconnaissance Regiment led by Lt Col Hankey. The observation posts were located along the sea dike at Colijnsplaat. The Zeelandia and Patrijs hotels provided a more comfortable shelter for the section and squadron headquarters. The population was asked to provide shelter for the Irene men. The soldiers shared their rations with the local residents. The field kitchen provided a menu with white bread, biscuits, cans of meat and butter, which the Zeelanders received with great enthusiasm. The following weeks consisted of long and especially cold days and nights with watchkeeping. There were three stone buildings on the seawall that served as an observation post. These buildings were originally built by Rijkswaterstaat and offered some shelter from the elements.

The first confrontation with the enemy took place in the night of 24 to 25 November. A twenty-six strong German patrol landed with orders to blow up certain waterworks. However, the patrol landed in the wrong place. They went to the nearest farm and gagged the farmer and the farmer's wife. They also stole a farmer's cart and loaded it full of explosives. A farmhand and an evacuee, who witnessed this, escaped unnoticed from the farm of the De Regt family and warned the Irene men in Colijnsplaat. After some doubts, Captain Immink sent Lieutenant Havelaar with two carriers to the farm. Before the farm was reached, the Germans opened fire. There was a huge firefight near a drainage sluice. Lieutenant Havelaar was killed in this fight.

Daan was present at this fight and Havelaar's death left a deep impression on him: "We were behind the dike and the gunfire came from the other side. Despite our warnings, the 'lute' raised his head above the dike to check with binoculars of the situation, and it was immediately over with him. A bullet hit him in the head.

After the lieutenant lay lifeless at the foot of the dike, the Germans surrendered. During the interrogations of the prisoners of war it became clear how great the disaster could have been if their intention had been successful. With the big quantities of explosives had to be blown up a drainage sluice, which would flood large parts of the island. In addition, they had the assignment to drive the male population of Colijnsplaat together in the Dutch Reformed Church, and then blow it up.

Just before Christmas 1944, German one- and two-person submarines were very active in the Western Scheldt and off the coast of Noord-Beveland. These submarines had the assignment to lay mines in the Scheldt estuary or to torpedo supply ships to prevent large supplies from reaching Antwerp. On December 24, a submarine was sighted, of which only the periscope was visible. The guard reported it by radio and this submarine was attacked by two planes. On Christmas Day a submarine was sighted in front of Domburg with the tower still above water, on which a man was visible. A Battle Group II post took the boat under fire with a captured 20mm Oerlikon (machine gun), causing it to sink from behind, put its nose in the air, capsize and sink completely. Moments later, another submarine was sighted, which exploded and sank after being under fire. The helmsman of a third became unconscious and the submarine washed up on the seawall at Westkapelle, where the navy man was taken prisoner.

Daan: "At Christmas, the exploration section in Colijnsplaat had a Christmas dinner. I remember someone with a three-ton truck was sent to Antwerp to pick up some drink rations there. The three-ton truck was completely full, but the next day almost everything was gone. The Christmas dinner was held in hotel Zeelandia in Colijnsplaat. According to an English tradition, which still exists today, the mess servants were also at the table during Christmas dinner. The non-commissioned officers served and the dessert was served by officers. Beautiful, then you sat there full of pride. I liked that. "

On December 28, information was received through the resistance in Zierikzee, which had a telephone connection with the liberated St. Phillipsland, that the Germans had gathered 4,000 men on Schouwen. There were also signals through other channels that the Germans were preparing an offensive to approach Antwerp from the north. Because the Ardennes offensive (the attack towards Antwerp from Luxembourg) had caused great unrest, the fear of a second invasion was extra great. As a result of the threat of an attack, on December 28 and 29, battle group I (stationed in Middelburg) and anti-aircraft guns of battle group III (Kapelle) and parts of the Reconnaissance Division were moved from North Beveland to North Walcheren.

At the beginning of February 1945, the High Command in London decided to release the marines from the Brigade on 1 April and to make them available again for their initial destination. As a result, the reconnaissance division had to be disbanded and the appropriate personnel assigned to it had to be assigned to Battle Group II.

On March 17, two of Daan's colleagues were killed in Vrouwenpolder. He said the following about this: “We had warned them so many times not to 'play with weapons', but it was said to deaf ears. Robert Paauwe and Jans Wieringa were killed because they wanted to shoot with a captured cannon. However, the Germans had left the weapon with a grenade in the barrel. The consequences could be guessed'.

Until his retirement at the end of 1977 he was employed as an inspector at Bouwfonds Nederland, an interviewer, an administrator at the Labor Office and until four months after his 65th birthday as a subsidiary at the Ministry of Culture, Recreation and Social Work. In the latter position he consulted with Mayors and Aldermen and gave subsidies for playgroups and playgrounds. This work was perfect for him. David van de Velde died on April 4, 1997 after a long illness in Eindhoven at the age of 84.

A warm thank you to Richard van de Velde, Daan's son.