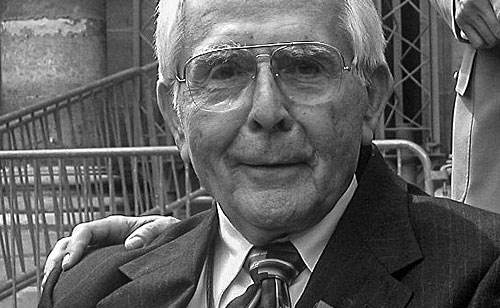

He had landed with the 115th Regiment on D-Day, fought in the Battle for Brest and across France, Belgium and into Germany, but nothing prepared 1st Lt. Alvin Ungerleider, a battle-hardened, twice- wounded soldier, for what he saw behind the gate of the Nazi slave labor camp at Dora-Mittelbau near Nordhausen, Germany on April 11, 1945.

“Suddenly we were in hell!” said Ungerleider, who was second in command of Company I of the Third Battalion. “We witnessed the sight of dead bodies, of human beings in the worst state of degradation.”

Lt. Ungerleider, just 23 years old at the time, was likely part of an advance party of the 115th, scouting routes and bivouac areas when they came to Dora-Mittelbau, according to Joseph Balkoski, 29th Division Historian.

“There were dead bodies everywhere. There were thousands of bodies.” said Morton Waitzman, who served with Lt. Ungerleider.

Nearly a year before liberating the camp, Ungerleider had led 50 men from the 115th Regiment ashore at Omaha Beach on the morning of June 6, 1944. They were in the second wave of U.S. troops who hit the beach in the Normandy invasion along the northern coast of France. The invasion changed the course of the war by leading to the Allied liberation of Western Europe from Germany’s control.

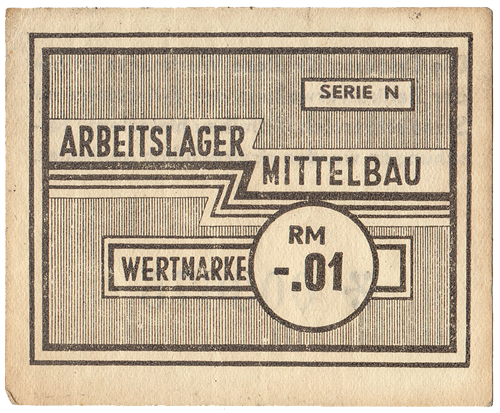

The prisoners at Dora-Mittelbau had dug tunnels for a huge German underground arms factory where V-2 missiles were to be manufactured, and then were forced to work on their production. While the 115th had been ordered toward Dora-Mittelbau, those orders were unexpectedly changed, and the Regiment redirected toward the Elbe River. However, Ungerleider and his men were apparently unaware of those new orders and continued toward the horrors that would greet his unit, along with members of the 104th Infantry and 821st Tank Destroyer Battalion.

“Al Ungerleider and I were together on this mission. As we neared the camp, we started to get machine gun fire from two small towers in the distance,” wrote Edward Burke in From Omaha Beach to the Elbe River. “Two of my tank destroyers destroyed the towers and my tank destroyer along with another crashed through the front gates. The machine gunners were killed, we captured about 44 prisoners and the rest of the Germans escaped,” wrote Burke.

“Those of us who were there, have to describe one of the main horrors was the intensity of the smell,” said Waitzman, “from those bodies that had been there for a while.” They found but a relative handful of living prisoners, perhaps 300. As the Germans realized defeat and the end of the war was near, in March they began moving over 30.000 slave laborers to hide their crimes, according to Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center.

Most were sent to their deaths at Bergen-Belsen, thousands were murdered en route. In one case, several thousand prisoners, mostly Jews, were burned to death in a barn near the village of Gardelegen. The figures that emerged from the wooden barracks at Dora-Mittelbau "were human cadavers," Ungerleider recalled. "They were sick. They could hardly stand. Others, covered with lice and sores, were too weak to crawl from their bunks.”

"There was absolute horror at what we saw. Then we asked, 'What can we do to help?'"

Ungerleider, a Jew, spoke Yiddish to the survivors and grouped the Jewish prisoners together to recite the Kaddish, the mourning prayer for the dead, and only then did the prisoners realize they had been liberated. "I cried all the way through it," he said. He and his men gave them the food they had, and Ungerleider then ordered nearby German villagers, who claimed ignorance of the slave labor camp, to return with food and warned them of their own punishment should they not.

Lt. Ungerleider and PFC William Melander then went to a building at one end of the camp and found the crematorium ovens inside with all of the doors closed. Ungerleider told Melander to bring his M1 Rifle ready to fire as he opened the first door. Ungerleider said as he approached the next door, he felt a tingle all through his body. As he opened the door, there was a German soldier with a Luger Pistol aimed at them. Fortunately, Billy was faster on the trigger and he pumped eight shots into the German as fast as he could pull the trigger.

Outside there was a railroad siding with two empty box cars. Their cargo of dead bodies had been stacked up like cordwood, 4 to 5 feet high against the back wall of the crematorium. While Ungerleider, who was later honored at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum as a liberator, had witnessed the carnage of D- Day, the bloody Battle for Brest and other terrors of war, what he saw at Dora-Mittelbau is what would haunt him for the rest of his life.

It was "burned into my brain and my soul like nothing else in my life. I've had many nightmares over the years about what happened at Nordhausen,” said Ungerleider who died in 2011 at the age of 89.

This account of Lt. Alvin Ungerleider’s role in liberating a Nazi slave labor camp was written by his son Neil Ungerleider in 2020 to mark the 75th anniversary of the day that brought freedom to many. Alvin Ungerleider served in World War II, Korea and Vietnam before retiring in 1978. He was awarded a Purple Heart with an Oak Leaf Cluster, the Bronze Star with three OLC, and the French Legion d’honneur. In 1994, he escorted President Clinton for the wreath laying at the American Cemetery in Normandy on the 50th anniversary of D-Day.

A big thank you to Neil Ungerleider.