Before the War

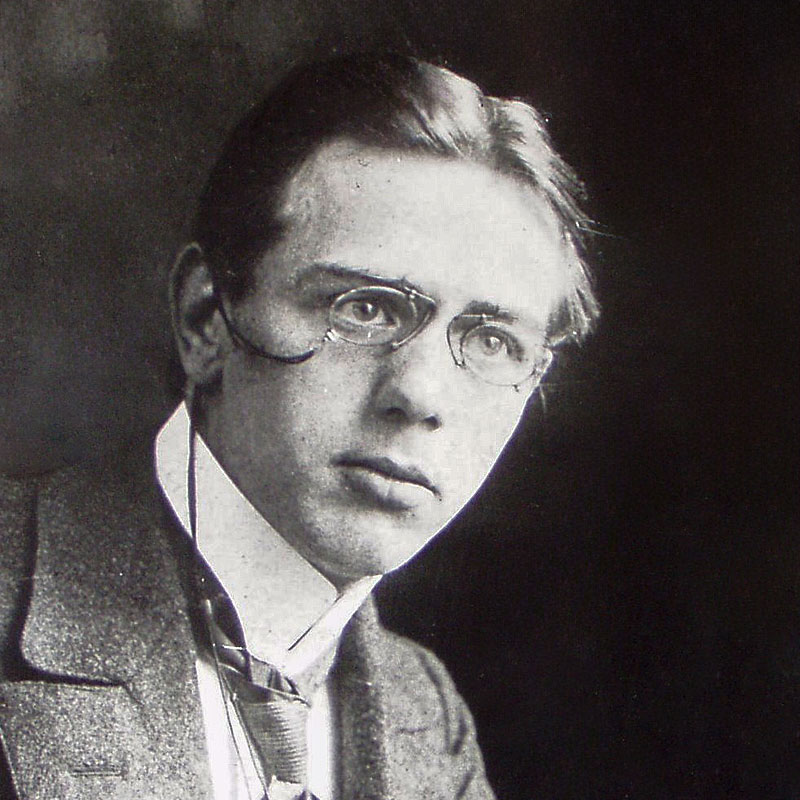

Before World War II, the Netherlands was a neutral country with a strong commitment to maintaining peace in Europe. The Dutch government, led by Queen Wilhelmina (31 August 1880 - 28 November 1962) and Prime Minister Hendrikus Colijn (22 June 1869 - 18 September 1944), focused on economic growth and social stability. The country had avoided involvement in World War I and hoped to do the same during rising tensions in the late 1930s.

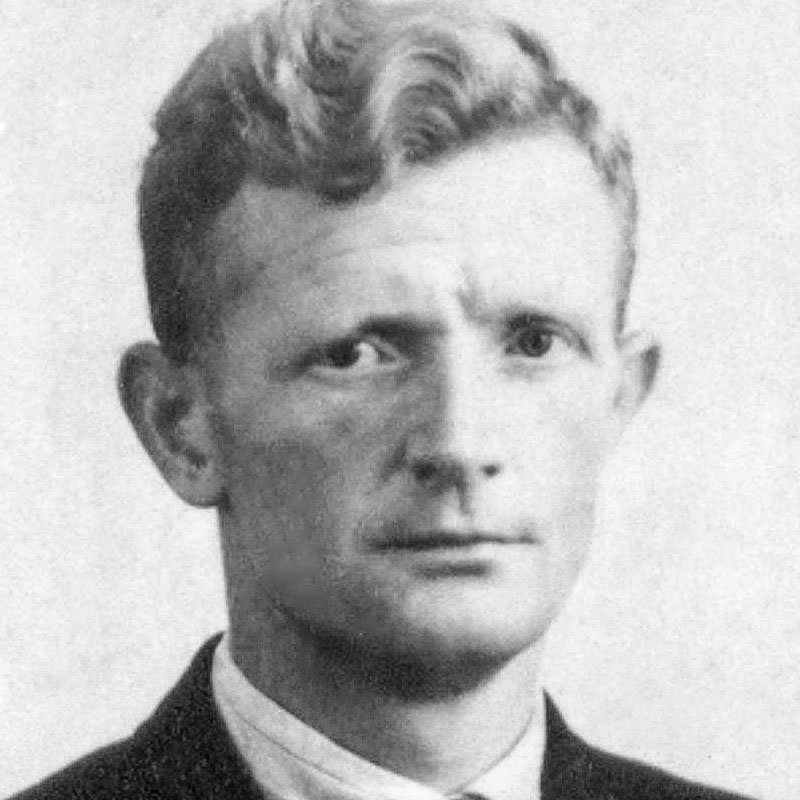

By the late 1930s, Europe was destabilised due to the aggressive expansion of Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler. The Netherlands maintained a policy of armed neutrality but began modest military preparations after Germany annexed Austria in 1938 and occupied Czechoslovakia in 1939. The Dutch army was under the command of General Henri Winkelman (7 March 1876 - 25 December 1952).

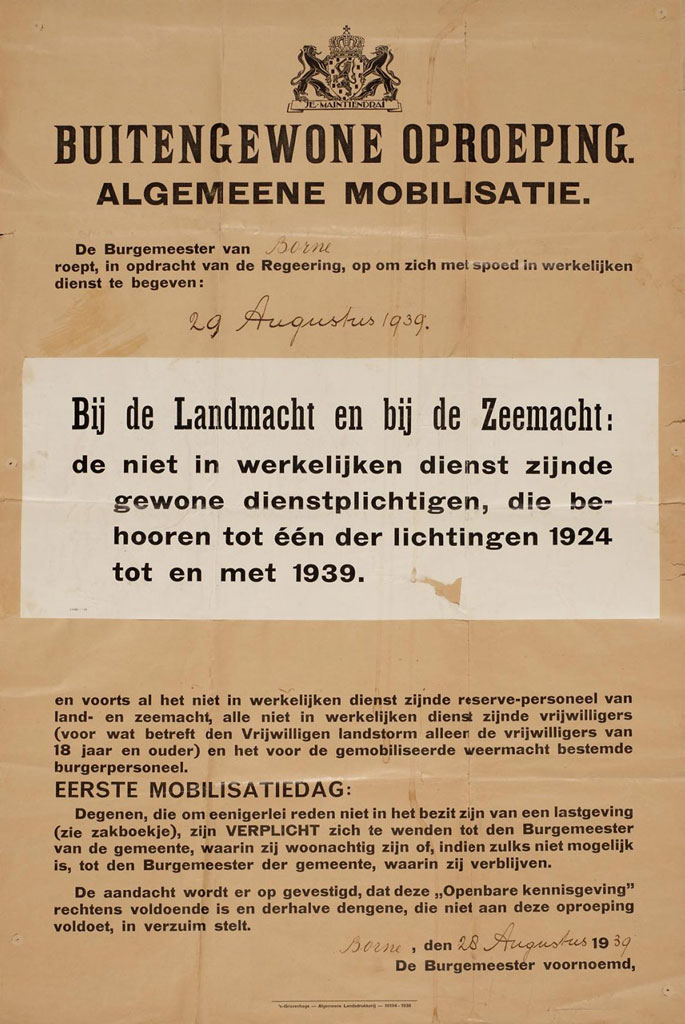

Dutch society was marked by a strong sense of cultural identity and religious diversity, with Protestant, Catholic and secular communities coexisting. Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and Utrecht were major urban centers, while the country’s extensive dikes and canals formed a unique geographic defence challenge. Due to the threat of war, the general mobilization of the Dutch army began on August 28, 1939, eventually numbering 300.000 men.

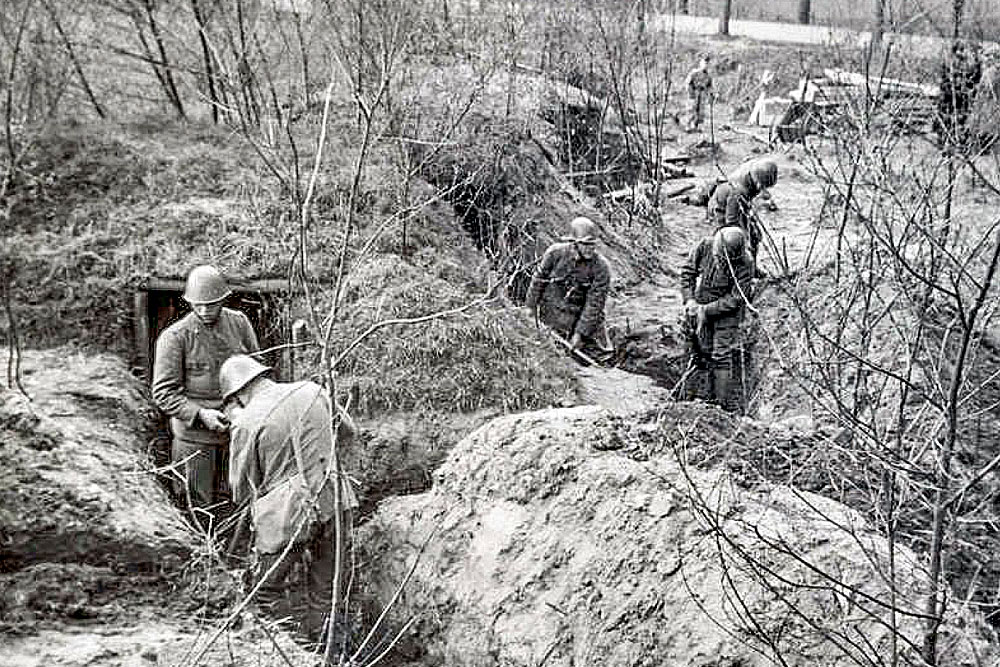

Despite its neutrality, the Netherlands was economically linked to neighbouring countries, including Germany. By May 1940, the government had the army on stand by, though Dutch forces were lightly equipped compared to the German Wehrmacht. The looming threat of war caused tension but little immediate disruption to everyday life.

Invasion and hostilities

The German invasion of the Netherlands, known as Fall Gelb (Case Yellow), began in the early hours of 10 May 1940, at approximately 05:35 AM. This military campaign was part of a broader German strategy to outflank the heavily fortified French Maginot Line by sweeping through the Low Countries, Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. The German army, under the overall command of Generalfeldmarschall Fedor von Bock, launched a surprise and highly coordinated offensive using a combination of rapid mechanized infantry, paratroopers, and overwhelming air power provided by the Luftwaffe.

The Dutch army, commanded by General Henri Winkelman, was unprepared for the scale and speed of the German assault. Despite mobilizing in advance of the invasion, the Netherlands had not significantly modernized its military forces in the interwar period and lacked sufficient tanks, anti-aircraft defenses, and combat aircraft. In contrast, the German military deployed advanced tactics, including the use of Blitzkrieg, a strategy emphasizing speed, surprise and concentrated firepower to devastating effect.

Major battles erupted in key strategic locations, including around the cities of Rotterdam, The Hague and in the southern province of Limburg. German paratroopers were dropped near The Hague in an attempt to capture the Dutch government and Queen Wilhelmina, though this part of the plan ultimately failed. Nevertheless, the ground offensive rapidly overwhelmed Dutch defenses. One of the most significant events during the invasion was the Bombing of Rotterdam on 14 May 1940, the mayor at that time was Pieter Oud (5 december 1886 - 12 augustus 1968). In a bid to force a swift Dutch capitulation, German bombers from the Luftwaffe attacked the city center, killing approximately 800 civilians and destroying large portions of the urban infrastructure. The resulting firestorm left tens of thousands homeless and broke the strong Dutch morale.

Despite isolated pockets of determined resistance most notably along 'The Grebbelinie' near Rhenen, Dutch forces were unable to withstand the superior coordination and firepower of the German army. On 15 May 1940, just five days after the invasion began, General Winkelman officially surrendered the Dutch military. In his surrender statement, he emphasized that continued resistance would only result in greater civilian suffering and loss of life.

Following the surrender, Queen Wilhelmina and the Dutch government fled to London, where they established a government-in-exile. This allowed the Dutch to continue supporting the Allied cause throughout the war. The swift fall of the Netherlands shocked both the Dutch population and the wider world. It marked a critical moment in the German conquest of Western Europe, as it enabled Germany to secure its northern and western flanks in preparation for the subsequent Battle of France.

The occupation years

The Netherlands was occupied by Nazi Germany from May 1940 to May 1945. The German military administration was headed initially by Arthur Seyss-Inquart (22 July 1892 - 16 October 1946), who became Reichskommissar for the occupied Dutch territories. His regime implemented harsh policies aligned with Nazi ideology, including the persecution of Jews and political dissidents. Dutch society faced severe restrictions: curfews, censorship, forced labor and rationing were imposed. The Nazi regime aimed to integrate the Dutch into the German Reich and used propaganda to gain collaboration.

In May 1940, Hanns Albin Rauter was appointed General Commissioner for Security and the top SS and Police Leader in the occupied Netherlands. As the highest Nazi official in charge of security, he orchestrated the deportation of 110.000 Dutch Jews to concentration camps, only about 6.000 survived.

The Nazis carried out large-scale raids, called razzias, across the Netherlands to arrest Jews, members of the resistance and young men for forced labor "Arbeidseinsatz" in Germany. These raids caused fear and panic, as people were taken from their homes, often without warning.

Some of the biggest razzias included:

- Amsterdam (February 1941): The first major roundup of Jews, leading to the famous 'February Strike' in protest.

- Rotterdam (November 1944): Over 50.000 men were taken in one of the largest razzias, forced to work in Germany.

- The Hague and Schiedam (1944): Thousands of men were arrested and deported during raids targeting resistance activity.

Many people went into hiding to avoid capture. These razzias left a lasting impact and are remembered as one of the darkest parts of the Nazi occupation in the Netherlands.

Star of David

On April 29, 1942, the Nazis announced a new humiliation for Dutch Jews. From May 3, they had to wear a badge of recognition: a six-pointed yellow Star of David with the word "Jew" in the middle.

One of the darkest periods was the systematic deportation of approximately 107.000 Dutch Jews. From Dutch concentration camps such as: Kamp Amersfoort and Kamp Vught, via the transit camp Westerbork in Drenthe, people were deported to concentration and exterminiation camps, such as Auschwitz and Sobibor in Poland. Among them was Anne Frank, born 12 June 1929, who went into hiding in Amsterdam and whose diary later became world-famous.

The occupation also brought economic exploitation. The Netherlands’ ports and industries supported the German war machine. Food shortages led to the Hunger Winter or "Hongerwinter" of 1944 - 1945, especially affecting the western provinces. Despite repression, underground newspapers, clandestine schools and resistance efforts continued. The occupation deeply affected Dutch culture and identity, sowing the seeds for post-war rebuilding and remembrance.

Resistance agains the occupier

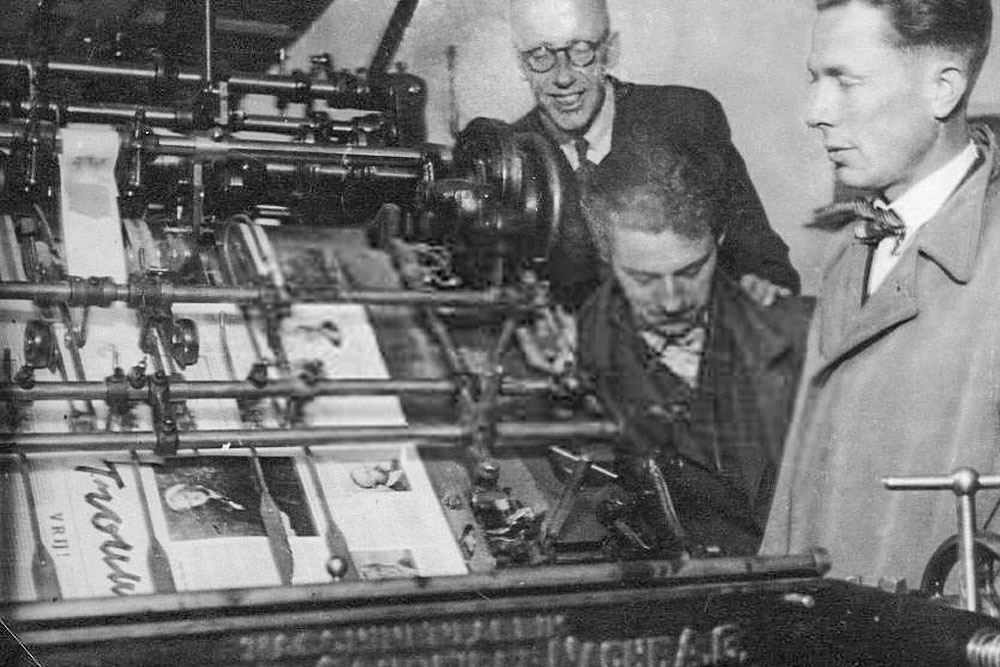

Despite overwhelming odds, the Dutch Resistance grew into a significant movement against Nazi occupation. It included a diverse array of groups from communists, socialists, religious organizations, to monarchists loyal to Queen Wilhelmina. The resistance engaged in sabotage, intelligence gathering, underground press production, and aiding Jews and political refugees. One of the notable leaders was Hannie Schaft (born 16 September 1920, executed 17 April 1945), known as "the girl with the red hair," who carried out assassinations of Nazi collaborators.

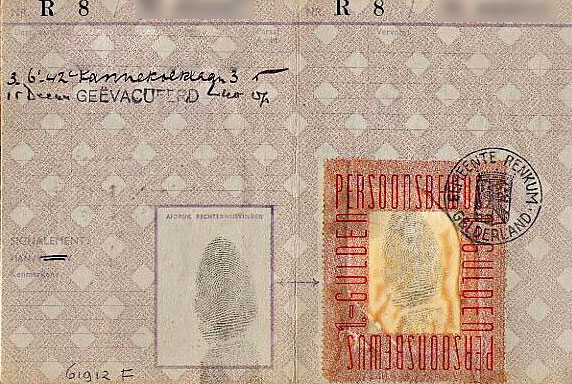

Forging identity cards

The Personal Identity Card Center (PBC) was a Dutch underground organization that provided the resistance and people in hiding with forged identity cards and other official documents during the Second World War. Under the leadership of Gerrit van der Veen, Walter Brandligt, Violette Cornelius, Maarten van Gilse, Nel Hissink, Dio Remiëns and Guusje Rübsaam formed the core of this group.

The group started making identity cards near writer Eduard Veterman’s studio, who had the same idea, but neither knew of the other’s work. Veterman and Van der Veen used almost identical methods; both acquired the needed typeface by ordering counterfeit printing and replicated the watermark similarly.

Sicherheits Polizei and Sicherheits Dienst

SS-Sturmbannführer Willi Lages (5 oktober 1901 - 2 april 1971) was head of the Sicherheits Polizei and Sicherheits Dienst in the Netherlands. He replaced Hellmuth Reinhard. Lages thus became partly responsible for the deportation of roughly 70.000 Jews from the Netherlands to concentration and extermination camps in Germany and occupied Poland. Lages was involved in the arrest of resistance fighter Johannes Post and was present at his execution and that of other resistance fighters on 16 July 1944. He was also responsible for the Operation Silbertanne (codename for executions that were reprisals for attacks by the resistance, mainly on Dutch collaborators. These executions, committed between September 1943 and September 1944, were carried out by a death squad composed of Dutch members of the SS and Dutch veterans of the Eastern Front), the murder of writer A.M. de Jong and for the execution of Hannie Schaft. After the war, Lages he was one of the 'Breda Four'.

The Landelijke Knokploegen (LKP) or National Assault Groups and the Ordedienst were prominent resistance organizations. They coordinated with the Dutch government-in-exile in London and Allied forces. A key event was the February Strike of 1941, a general strike protesting the deportation of Jews in Amsterdam, marking one of the first public acts of resistance in occupied Europe.

Resistance fighters risked torture and execution by the Gestapo. Despite losses, their efforts disrupted German logistics and helped protect many lives.

Liberation

The liberation of the Netherlands began on 17 September 1944 with Operation Market Garden, a bold Allied plan to capture key bridges in Eindhoven, Nijmegen, and Arnhem in hopes of ending the war by Christmas. The operation was led by British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery and combined airborne and ground forces. Airborne troops under Lieutenant General Lewis H. Brereton landed near Eindhoven, while ground forces from XXX Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Brian Horrocks, advanced north to link up with them. At Arnhem, Major General Roy Urquhart’s British 1st Airborne Division was dropped too far from its target and became isolated around the Arnhem Bridge. To support them, Major General Stanisław Sosabowski and the Polish 1st Independent Parachute Brigade were deployed near Driel, but were unable to break through the German resistance in time.

Operation Market Garden failed

Dut to unexpected German resistance, poor intelligence and logistical issues especially at Arnhem, where British and Polish forces were overwhelmed, led to the operation's failure. Despite some gains in the south, the operation did not achieve its goal of crossing the Rhine and hastening Germany's defeat. This battle became also known as a 'Bridge too far'.

Battle of the Scheldt

The Battle of the Scheldt (October - November 1944), commanded by Lieutenant General Guy Simonds of the First Canadian Army (under General Harry Crerar), was critical to open the port of Antwerp for Allied supply lines.

Liberation progressed slowly due to fierce German resistance and harsh winter conditions. The southern provinces were freed by late 1944, but much of the north remained under German control until May 1945. Canadian, British, and Polish forces otably under commanders like General Crerar, Major General Stanisław Maczek (1st Polish Armoured Division) and General Charles Foulkes played a major role in liberating the Netherlands.

Liberation of The Netherlands

On 5 May 1945, German Generaloberst Johannes Blaskowitz formally surrendered German forces in the Netherlands to General Foulkes in Wageningen. The Dutch Prince Bernhard of the Netherlandswas present.

The Dutch celebrated their freedom, mourning those lost and beginning the difficult process of recovery.

Rebuilding

Post-war reconstruction in the Netherlands was a monumental task. The country faced devastated cities, destroyed infrastructure, and social trauma. Queen Wilhelmina returned in 1945, passing the crown to her daughter Juliana (born 30 April 1909, died 20 March 2004) who became queen in 1948.

The Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan aid from the United States accelerated economic recovery. Cities like Rotterdam were rebuilt with modern architecture to replace wartime destruction. The government focused on restoring democracy, purging collaborators, and memorialising the victims of war. The Dutch economy diversified, and by the 1950s the country entered a period of rapid growth.

The legacy of World War II continues to shape Dutch culture, with museums, memorials, and education dedicated to remembrance and peace.

Beyond the Headlines: Every Nation’s Story in WW2

Highlighting these diverse stories honors the millions of civilians and soldiers whose voices are often overlooked. It helps us understand the full impact of the war, not just through battles and politics, but through personal resilience, cultural loss, and national recovery. By shedding light on each country's experience, we build a more complete, inclusive, and human story of WW2, one that educates, connects and reminds us why peace and remembrance matter.