History of Warsaw

History of Warsaw ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto in Warsaw, Poland, was the largest Jewish ghetto established by Nazi Germany during the Holocaust in World War II. During the ghetto's three-year existence, malnutrition, disease and deportations to concentration and extermination camps reduced the population from an estimated 450.000 to 37.000 people. Exactly how many people stayed in the ghetto is unknown, estimates vary between 450.000 and 560.000. In 1943 the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising took place here, one of the first mass uprisings against the Nazis occupying Europe.

Creation of the ghetto

Plans to isolate the Jewish population of Warsaw and its suburbs surfaced immediately after the German occupation of Poland in 1939. In 1939 the German General Government was not yet fully organized and there was a difference of interest of the three main parties: the civilian government, the German army and the SS. Due to these circumstances, the Jewish Council (Judenrat) in Warsaw, headed by Adam Czerniaków, had managed to delay the establishment of the ghetto by a year, mainly by pointing out to the military the value of Jews as workers. The Ghetto was located in a part of Warsaw where many Jews had traditionally lived; the Jewish quarter. Non-Jews had to leave the neighborhood, Jews who did not live in the neighborhood had to leave their homes and settle in the ghetto. The closure of the ghetto in Warsaw took place on November 16, 1940. The decision delineating its area was issued by the head of the Warsaw district of the General Government, Dr. Ludwig Fischer, October 2, 1940.

Social and cultural life in the ghetto

Despite the incredible rigors of everyday life, the Judenrat and the youth movements managed to set up various institutes and organizations to meet the different needs of the residents. The biggest problems were overcrowding, hunger and inactivity. In response, the Judenrat took on the responsibility of allocating housing - an average of seven people per room - while charities like CENTOS set up kitchens where free soup was distributed: at one point, two-thirds of the ghetto's population was making soup. For a short time, the Judenrat was also allowed to establish four primary schools for the children of the ghetto, but there was also an extensive underground school system of the various youth movements, offering all levels (often disguised as kitchen), and the system even organized college-level courses on Sundays.

The Judenrat was also responsible for the hospitals and orphanages in the ghetto. One orphanage, run by the pediatrician and author Janusz Korczak, was set up as a model democracy, the Children's Republic. These and other orphanages were evacuated in 1942 and their residents were transferred to Treblinka.

Cultural life consisted of a lively press in three languages (Yiddish, Polish and Hebrew), religious activities, and lectures, concerts, theatrical performances and exhibitions. In many cases the performers were prominent figures in Polish cultural life during the war.

One of the most notable cultural efforts in the ghetto was that of historian Emmanuel Ringelblum and his group Oyneg Shabbos, who collected documents from people of all ages and positions to create a history of social life in the ghetto. In total, an estimated 50.000 documents were collected. These documents were hidden in three separate groups, two of which have been found and have provided an indispensable insight into life in the ghetto.

The Warsaw Ghetto was placed under command of the German Governor General Hans Frank on October 16, 1940. The Judenrat was given administrative control of the ghetto, they had to carry out the orders of the Germans. When it was founded, the population of the ghetto was estimated at about 380.000 people, which was about 30% of the population of Warsaw. The ghetto occupied 2.4% of Warsaw's territory, making the ghetto overcrowded from the start. Nazis built a wall around the ghetto on November 16, 1940, cutting it off from the outside world. The Germans and the Polish police monitored who went in and out of the ghetto, in the ghetto law enforcement was in the hands of Germans, the Polish police and some 2.000 German-appointed Jews, the Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst. In the year and a half following the ghetto's establishment, Jews from smaller towns and villages were brought into the ghetto. Despite this increase, the population remained about the same and even decreased in 1942 because many inhabitants of the ghetto died of diseases (mainly typhus) and malnutrition.

Annihalation of the ghetto

In early 1942, at the Wannsee Conference, the Nazis decided to destroy the Jews of Europe. The first sentence of the 'final solution' (Endlosung der Judenfrage) was Operation Reinhard, which aimed to destroy all Polish Jews. Construction of Treblinka extermination camp began in May 1942 and was completed in July 1942, when the large-scale destruction of the Warsaw Ghetto was about to begin.

On July 22, 1942, the Judenrat was informed that all Jews would be deported 'to the east'. There were also groups of Jews who would initially be spared, these were Jews who worked in German factories, Jewish hospital staff, members of the Judenrat and their families, and members of the Jewish police force and their families. The Jewish police were ordered to deliver 6.000 Jews to the train station (known as Umschlagplatz) every day. Failure to do so would lead to the immediate execution of 100 hostages, including Czerniaków's wife. Czerniaków tried to convince the Germans to reconsider their plans, also asked them to at least spare the children and if that was not possible, at least spare the orphans of the ghetto. However, the Germans did not heed Czerniaków's plea, after which Czerniaków committed suicide on July 23, 1942. Czerniaków left a letter in which he wrote: "I can no longer take this. My deed will prove to everyone what the good is to to do". On July 23, members of the Jewish resistance gathered, but decided not to resist because they still believed that the Jews were being sent to labor camps.

The mass deportations of the residents, as ordered on July 22, began. In the next 52 days (until September 21), about 300.000 people were transported to the Treblinka extermination camp. Initially, the Jewish police were responsible for the deportations, in July 64.606 Jews were sent to the extermination camps. From August, the Germans took a more direct role in the deportations, ensuring that 135.000 Jews were deported in August alone.

In that same day, 35.885 Jews were deported, 2.648 were shot in the ghetto and 60 Jews committed suicide. After September 10, about 55.000 to 60.000 Jews continued to live in the ghetto. These people were either working in German factories or living hidden in the ghetto.

Over the next six months, the remnants of several political organizations were brought together under the name ŻOB (Jewish Combat Organization), led by Mordechaj Anielewicz, with 220-500 members; 250-450 others were organized in the Żydowski Związek Wojskowy (ŻZW) (Jewish Warriors' Union). The members of these groups had no illusions about the plans of the Germans and wanted to die fighting. Their armament consisted mainly of handguns, homemade explosives and Molotov cocktails.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Destruction of the Ghetto

On January 18, 1943, the first armed resistance took place when the Germans began the second eviction of the ghetto. The Jewish fighters had some success: the deportation stopped after four days and the ŻOB and the ŻZW took control of the ghetto. They built dozens of combat posts and took action against Jewish collaborators. Over the next three months, all the residents of the ghetto prepared for what would be the final battle. This last battle began the day before Passover, April 19, 1943. Jewish fighters fired at German patrols from alleys, sewers, homes and even burning buildings. Grenades were also thrown at Germans. The Nazis responded by blowing up houses block by block and arrested every Jew they got their hands on, these Jews were all later killed. Significant resistance ended on April 23, the uprising ended on May 16. About 7.000 Jewish fighters were killed in the fighting and another 6.000 were burned alive or gassed in bunkers. The remaining 50.000 people were sent to death camps, most of them to Treblinka.

Mordechai Anielewicz: The Flame of Resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto

Mordechai Anielewicz (1919 – May 8, 1943) stands as one of the most heroic and enduring symbols of Jewish resistance during the Holocaust. Born in the small town of Wyszków, Poland, in 1919, Anielewicz grew up during a time of mounting tension and growing antisemitism in Europe. As a young man, he joined Hashomer Hatzair, a Zionist-socialist youth movement that instilled in him a belief in Jewish self-determination, education, and social justice.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland in 1939, many Jews fled or were forcibly deported. But Anielewicz chose to stay, determined to organize and support the Jewish underground resistance. As the situation worsened and Jews were confined to ghettos, he traveled through occupied Poland, encouraging defiance and building a network of fighters.

In the summer of 1942, the Warsaw Ghetto experienced one of its darkest moments the mass deportation of over 250.000 Jews to the Treblinka extermination camp. The scale of the atrocity galvanized what remained of the Jewish community. In response, Anielewicz became the leader of the newly formed Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa (ŻOB), or Jewish Combat Organization. Under his leadership, the ŻOB began preparing for armed resistance — smuggling weapons, training young fighters, and coordinating with other underground movements.

The culmination of these efforts came on April 19, 1943, when German forces entered the Warsaw Ghetto to deport its remaining inhabitants. Instead of surrendering, Anielewicz and his small band of fighters launched a bold and unprecedented rebellion. Despite being vastly outgunned and outnumbered, the resistance held off German troops for nearly a month. The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising became the largest act of Jewish resistance during World War II.

Tragically, on May 8, 1943, Mordechai Anielewicz and many of his comrades died in a bunker at 18 Mila Street, likely choosing suicide over capture as German forces closed in. Though the uprising was eventually crushed, its moral and symbolic victory was profound. It shattered the myth of Jewish passivity and inspired future resistance movements across Europe.

Anielewicz’s legacy endures as a beacon of bravery, defiance, and sacrifice. In Israel, a kibbutz named Yad Mordechai honors his memory, alongside streets and monuments bearing his name, including Mount Anielewicz. His story continues to be taught around the world as a testament to the human spirit's refusal to surrender to tyranny.

Mordechai Anielewicz did not live to see liberation, but his courage left a permanent mark on history. He remains one of the most revered figures of the Holocaust, a young man who chose to fight, and who became the face of Jewish resistance against the Nazis.

460000

92000

307000

Location map

OpenStreetMap service required

to load this map.

OpenStreetMap service required

to load this map.

Location: Warsaw, Poland

Liberation of Warsaw

On August 1, 1944, the Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa), loyal to the Polish government-in-exile in London, launched the Warsaw Uprising in a bid to liberate the city from German control before the Soviets arrived. The uprising was meant to assert Polish sovereignty and prevent a Soviet-backed communist regime from taking over. However, the Soviet advance stalled on the eastern bank of the Vistula, and the Red Army did not intervene. This led to controversy and accusations that the Soviets deliberately halted their offensive to allow the Germans to crush the uprising and eliminate the non-communist Polish resistance.

The Warsaw Uprising lasted 63 days, during which Polish fighters and civilians were subjected to a devastating German counteroffensive. By early October 1944, the uprising was defeated. The Germans systematically destroyed large parts of the city in retribution, and Warsaw was left in ruins.

Soviet regrouping

Over the next few months, the Red Army regrouped and prepared for a renewed offensive. On January 12, 1945, Soviet forces launched the Vistula Oder Offensive, a massive assault aimed at pushing German forces out of Poland and moving toward Berlin. The offensive quickly overwhelmed the weakened German defenses.

On January 17, 1945, Soviet troops of Marshal Georgy Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front entered Warsaw. The city, nearly deserted and heavily damaged, was taken with little resistance. The Germans had already begun retreating in the face of the overwhelming Soviet advance. Warsaw was now under Soviet control.

While the liberation ended Nazi occupation, it also marked the beginning of Soviet domination in Poland. The Polish government-in-exile was sidelined, and a communist government loyal to Moscow was installed. For many Poles, liberation from one totalitarian regime was followed by the imposition of another.

Nevertheless, the liberation of Warsaw on January 17, 1945, remains a significant milestone. It ended the Nazi grip on the city and opened the path for the final push toward Berlin, which would bring the war in Europe to a close just months later.

Text partially derived from from ushmm.org

Perpetrators of the Warsaw ghetto

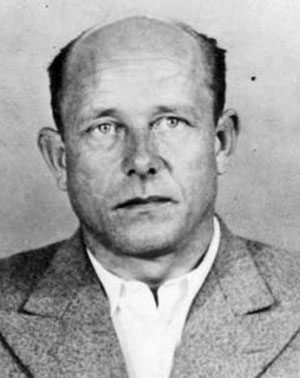

Governor Ludwig Fischer

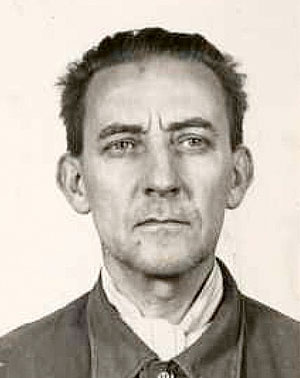

SS Kommissar Heinz Auerswald

SS Oberführer Ferdinand von Sammern-Frankenegg

SS Gruppenführer Jürgen Stroop