Nathan Wijnperle

A leap to freedom and the promise that defied Auschwitz

A childhood in prewar Jewish Sittard

Before the war, Jewish life for Nathan Herman Wijnperle in Sittard was visible, stable and deeply rooted. Families lived among their neighbours without segregation. Religious practice shaped private life, while civic participation connected Jewish residents to the wider town. The community was small, but its traditions were old. Grandparents carried memories of earlier generations and children inherited rituals that had crossed borders and centuries.

For Nathan, childhood meant warmth, predictability and belonging. The rhythms of Jewish observance were not restrictive; they were comforting. Meals followed ritual law. Holidays punctuated the year. Education emphasised moral responsibility as much as literacy. The town itself felt safe. Identity did not yet carry danger.

This early stability makes the later rupture even more devastating. The memoir constantly contrasts memory with aftermath. What was destroyed was not abstract culture, it was a lived daily world.

From restriction to persecution

After the German occupation, discrimination arrived gradually but relentlessly. Jewish identity became a legal category enforced by paperwork. Registration separated citizens from neighbors. Restrictions narrowed opportunities. Public space became increasingly hostile.

For families like the Wijnperles, survival meant adaptation. The Jewish community grew inward-facing. Parents tried to shield children from fear, but tension was impossible to hide. Rumors of deportation spread. People vanished from streets and schools. The town that once felt unified became fractured.

Nathan was old enough to understand that something irreversible was unfolding, yet young enough to resist accepting it fully. Adolescence collided with catastrophe.

The promise

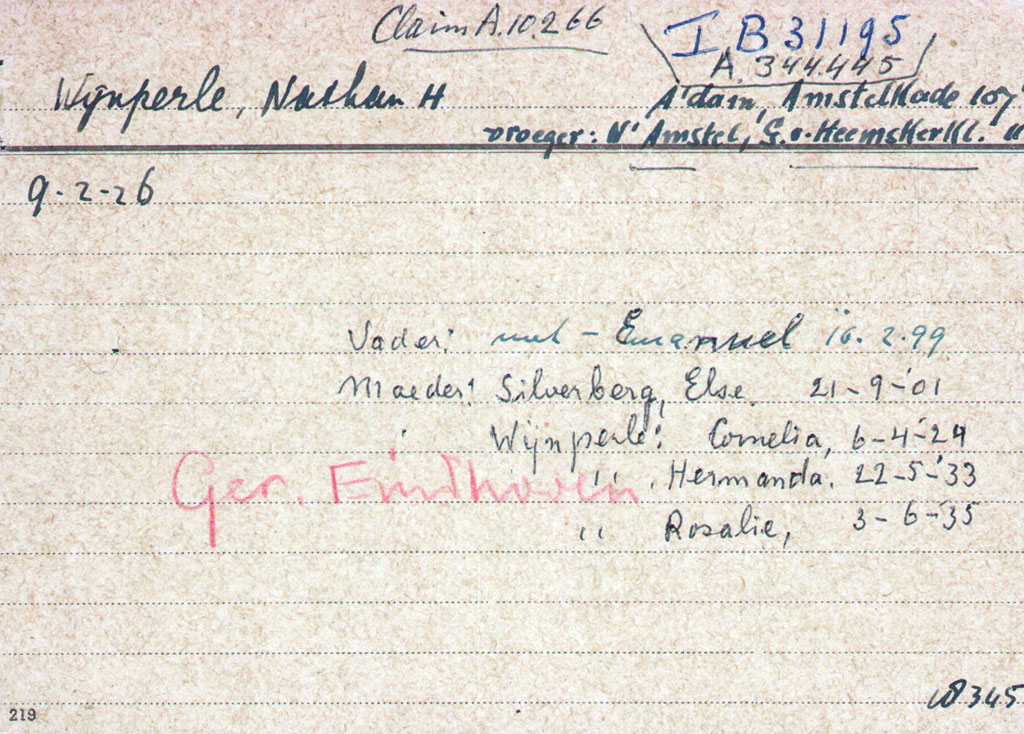

When Nathan and his parents went into hiding in Amsterdam, survival required stillness. Hiding meant silence, patience and invisibility. For a sixteen-year-old, the confinement was psychologically unbearable. He longed for a moment of normal life.

His arrest on 6 January 1943 ended that illusion instantly. The interrogation, the forced betrayal of his family’s hiding place and the arrest of his mother formed a traumatic break. Nathan later carried deep guilt about this moment, even though he had been a child under extreme coercion. His father’s escape from capture would become one of the few fragments of luck in a chain of catastrophe.

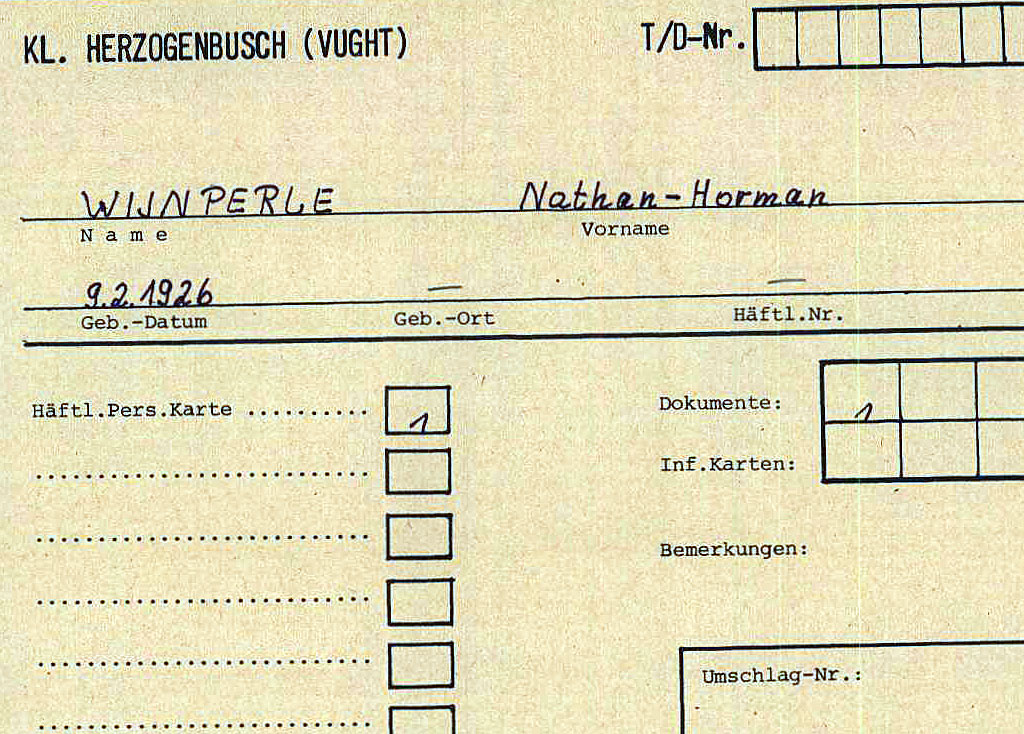

In Camp Vught, the machinery of deportation became visible. Lists, categories and punishments defined human fate. Nathan and his mother were separated. Their status as penal prisoners made deportation to Auschwitz almost certain. It was here, in the shadow of extermination, that Nathan made his promise:

“Mom, I promise you, we're not going to Germany.”

It was a promise born of defiance rather than strategy, but he meant it absolutely.

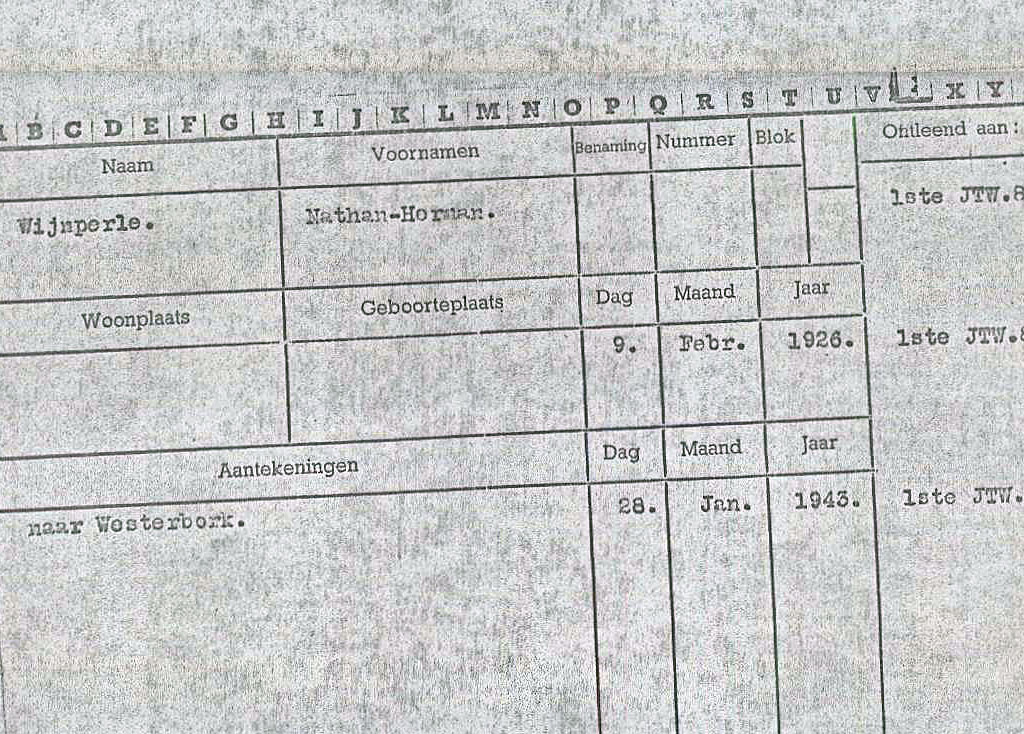

The transport of 28 January 1943

On 28 January, Nathan and Else were summoned for deportation to Westerbork. Neither knew the other would be on the same transport. Prisoners were marched to the station under guard, surrounded by fear and resignation. At the platform, Else caught sight of her son. Through instinct and extraordinary courage, Nathan managed to slip into the women’s group. With a handkerchief tied around his head, he disguised himself just enough to avoid immediate detection. Mother and son were placed in the same compartment of the steam train bound east.

The train represented a one-way journey into the machinery of death. Inside the compartment, Nathan positioned himself near the door. He began studying the lock. Every movement had to appear accidental. Every second carried risk.

A Dutch railway guard noticed.

Later identified as Mr. Jooren, the guard made a silent decision that would alter history. While a German guard looked elsewhere, he manipulated the mechanism and left the door imperfectly secured. It was an act of quiet resistance, small in motion, enormous in consequence.

Nathan understood what had been given to him: a chance.

The leap

As the train moved, Nathan observed its rhythm. At each station it slowed. When pulling away, steam clouds obscured visibility. He measured time, speed and opportunity. He remembered his promise. When the moment came, he did not hesitate. He jumped.

His mother, Else, hesitated for a fraction of a second, the natural human reaction to a leap into uncertainty. Nathan grabbed her hand and pulled her with him. Together they hurled themselves from a moving deportation train on its way to Auschwitz. The impact was violent. The ground tore skin and breath away. For a moment there was only shock. But they were alive. On that winter day in January 1943, mother and son literally leapt out of extermination. It was not symbolic resistance. It was physical refusal. The promise had been kept. They did not go east.

Escape does not mean safety

Freedom after the jump was immediate but fragile. Nathan and Else were injured, disoriented and still in occupied territory. Recapture meant certain deportation. Every stranger could be danger; every step required trust. They were taken in by members of the resistance in Dieren. These civilians risked execution to shelter fugitives. Father Koets opened his door when the pair appeared unexpectedly. Toon and Dien Smulders hid them for several days. Dr. Vermeer arranged their transfer deeper into resistance networks.

Each act of assistance was a conscious gamble against Nazi terror. Survival depended not only on Nathan’s leap but on the courage of others who chose humanity over fear.

Reunion in Limburg

After days of movement and concealment, Nathan and Else reached the harbour of Born in Limburg. There they were reunited with Nathan’s father. The reunion was emotional but brief in its relief. The family remained hunted. Their survival now depended on long-term hiding. They found refuge aboard the ship of Kees and Lieske Zwaans, resistance members who sheltered them for nearly a year and a half. The vessel became both prison and sanctuary. Life aboard required silence, discipline and constant vigilance. Discovery meant execution, not only for the family but for their protectors.

Nathan passed from adolescence into adulthood under these conditions. Time stretched. Every day survived was an act of quiet endurance.

Liberation

When liberation finally arrived, it did not erase what had been lost. The Netherlands emerged from occupation scarred and emptied. The Jewish communities that had once filled towns like Sittard were largely destroyed. Nathan’s family had survived through a chain of improbable decisions, courage and assistance. Many others had not. Survival carried its own burden: the knowledge that chance and resistance had separated life from death.

The weight of memory

Nathan’s later reflections show that survival did not bring simple relief. It created responsibility. Those who escaped had to speak for those who did not return. Memory became a moral duty. The leap from the train was not only a personal act; it became testimony. It demonstrated that even inside the machinery of genocide, human agency could exist. It did not undo the Holocaust, but it asserted dignity against annihilation. Nathan wrote so that the vanished Jewish world of his childhood would remain visible. His story restores individuality to history. It reminds us that behind statistics stood children, parents, promises and impossible decisions.

Legacy

Today, Nathan Wijnperle’s leap is remembered not as an adventure, but as a declaration of humanity. It represents resistance at its most intimate scale: a son refusing to surrender his mother to a system built for extermination. His promise, “we’re not going to Germany”, echoes across generations. It is a reminder that memory is not passive. It is an active force that keeps erased worlds present.

By telling this story, we do more than recount an escape. We restore a life, a family and a community to the historical record. And in doing so, we keep the promise alive.

Timeline, from childhood to liberation

Below is a timeline of the story

1920

Nathan Wijnperle is born in Sittard, in the southern Netherlands, into a Jewish family deeply rooted in religious tradition and local community life.

1920's - 1930's

Nathan grows up in *prewar Jewish Sittard*. Jewish and non-Jewish residents live side by side. Family life is shaped by kosher practice, Jewish education and community solidarity.

1933 - 1939

News of antisemitic persecution in Nazi Germany reaches the Netherlands. Many Dutch Jews believe their country will remain safe.

10 May 1940

Germany invades the Netherlands. Occupation begins. Jewish citizens are gradually isolated through registration, restrictions and exclusion.

1941 - 1942

Persecution intensifies. Deportations begin. Jewish families disappear from towns and cities. Nathan and his parents eventually go into hiding in Amsterdam.

6 January 1943

Sixteen-year-old Nathan is arrested on the Rokin in Amsterdam, outside the V&D department store, by Jewish hunter Abraham Puls. After interrogation, his mother Else is arrested. His father avoids capture.

January 1943

Nathan and Else are imprisoned and transferred as *penal prisoners* to Camp Vught. They are separated. Their punishment status makes deportation to Auschwitz likely.

28 January 1943, morning

Nathan and Else are summoned for deportation. They are marched to the station under guard. At the platform, mother and son unexpectedly spot one another.

28 January 1943, transport

Nathan disguises himself with a handkerchief and joins the women’s group so he can remain with his mother in the same train compartment. A Dutch railway guard discreetly loosens the door lock.

28 January 1943, escape

As the train departs and slows between stations, Nathan jumps from the moving train. He pulls his mother Else with him. They escape from a deportation train bound for Auschwitz.

Late January - February 1943

Nathan and Else receive help from members of the Dutch resistance in Dieren. They are hidden and transferred through multiple safe locations.

1943

They reach Born, Limburg, where they are reunited with Nathan’s father.

1943 - 1944

The family remains in hiding for nearly a year and a half aboard the ship of resistance members Kees and Lieske Zwaans.

1944 - 1945

Liberation of the Netherlands. Nathan and his parents survive, an outcome rare among Dutch Jews deported during the Holocaust.

Postwar years

Nathan carries the responsibility of survival. He later records his memories to preserve the destroyed Jewish world of his childhood and to testify to resistance and human courage.

Personal images

Click the images to enlarge

Share on social media

The stories on my website educate about WWII. Please help by sharing them with your family, friends and on social media. Thank you!