Between 1933 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its allies established more than 44.000 camps and other incarceration sites. The perpetrators used these locations for a range of purposes, including forced labor, detention of people deemed to be "enemies of the state," and mass murder. Millions of people suffered and died or were killed. Among these sites was the Flossenbürg camp and its subcamps. On March 24, 1938, SS authorities determined a site near the small town of Flossenbürg to be suitable for the establishment of a concentration camp, due to its potential for extracting granite for construction purposes. The site lay in northeastern Bavaria near the Czech border, less than ten miles northeast of Weiden.

"For evil to flourish, it only requires good men to do nothing".

Simon Wiesenthal

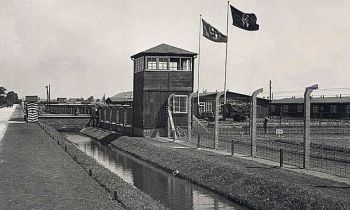

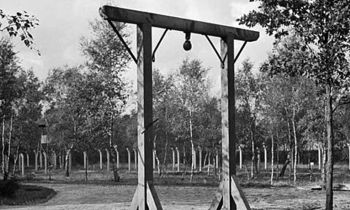

Main gate at Flossenburg supporting the slogan "Arbeit macht Frei"

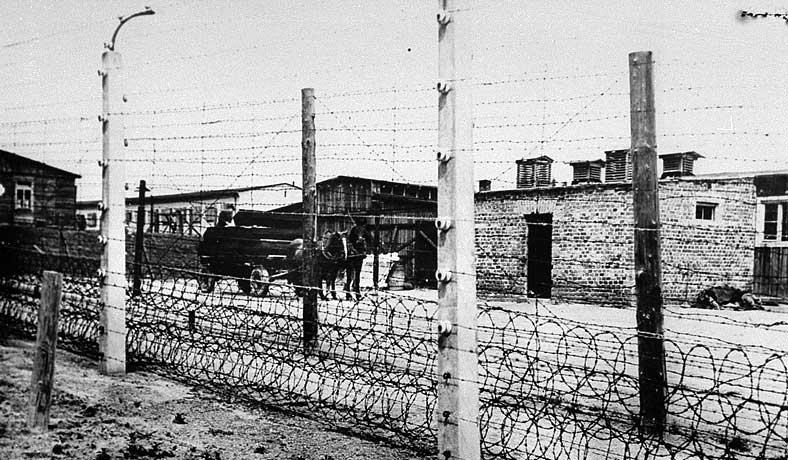

The electrical and barbe wired fences

An overview of the barracks surrounded by the guard towers

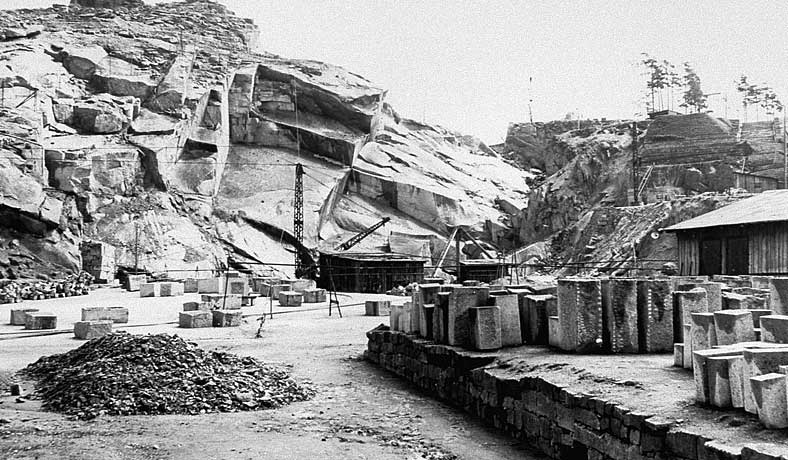

The infamous quarry

Sleeping barracks of the prisoners

Ramp leading down to the crematorium camp

The crematorium at Flossenburg

A guide shows an 97th Infantry Divison officer the crematorium

Another view of the camp layout

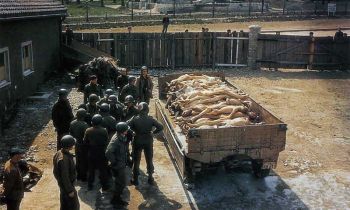

Prisoners who could not proceed on the death march were shot and left

Body piles Jewish, French, Russian and Slav slave laborers

Local girl expresses horror at sight of murdered Russians, Czechs and French, the bodies exhumed by US troops and ordered civilians to rebury them

- Main gate at Flossenburg supporting the slogan "Arbeit macht Frei"

- The electrical and barbe wired fences

- An overview of the barracks surrounded by the guard towers

- The infamous quarry

- Sleeping barracks of the prisoners

- Ramp leading down to the crematorium camp

- The crematorium at Flossenburg

- A guide shows an 97th Infantry Divison officer the crematorium

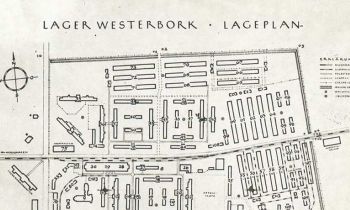

- Another view of the camp layout

- Prisoners who could not proceed on the death march were shot and left

- Body piles Jewish, French, Russian and Slav slave laborers

- Local girl expresses horror at sight of murdered Russians, Czechs and French, the bodies exhumed by US troops and ordered civilians to rebury them

History, definition and facts about Flossenbürg

Flossenbürg - Granite site

Before the establishment of the concentration camp, Flossenbürg was merely a small village in the Upper Palatinate forest. Beginning in the late 19th century, a number of quarries were opened in the area in order to exploit local granite deposits, and Flossenbürg developed into a workers’ village.

At the same time, the region was discovered as a holiday destination. After the National Socialist seizure of power, the granite deposits and castle became the site’s key locational factors. The quarry industry shaped social relations in the village and influenced the culture and self-perception of its inhabitants.

Flossenbürg remained a destination for day trippers. The border region increasingly drew nationalist and völkisch groups, which stylized the ruins as a bastion of resistance to the “Slavic peoples.” The National Socialist state construction program created a boom in the demand for granite. As a result, quarry owners and workers welcomed the National Socialist seizure of power.

Founding of the Flossenbürg Camp

The Flossenbürg camp was established in May 1938 during the SS reorganization of the entire concentration camp system. In the new system, the purpose of the camps was no longer only to imprison and terrorize political opponents of the Nazi regime. Rather, the SS now also aimed to profit from the exploitation of prisoner labor. Prisoners were put to work in SS-owned economic enterprises for the production of building materials. To this end, the SS founded new camps, and deported ever larger numbers of people to the camps.

The construction of new camps began in 1936-37 with the founding of the Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald camps. SS economic interests played an increasing role in the selection of new camp sites. The large granite deposits around Flossenbürg attracted the attention of the SS. The decision on the Flossenbürg site was reached in March 1938. The first SS guards arrived in late April. On May 3, the first transport of 100 prisoners arrived at the construction site from the Dachau concentration camp. By the end of 1938, the initial intake of the camp had increased to 1,500 prisoners.

Arbeit macht frei

The Flossenbürg Camp also supported the slogan "Arbeit macht frei" like the camps: Dachau, Sachsenhausen, Auschwitz, Gross Rosen and Theresienstadt in the Czech Republic. The expression comes from the title of an 1873 novel by German philologist Lorenz Diefenbach, Arbeit macht frei: Erzählung von Lorenz Diefenbach, in which gamblers and fraudsters find the path to virtue through labour. The phrase was also used in French (le travail rend libre!) by Auguste Forel, a Swiss entomologist, neuroanatomist and psychiatrist, in his Fourmis de la Suisse (English: "Ants of Switzerland") (1920). In 1922, the Deutsche Schulverein of Vienna, an ethnic nationalist "protective" organization of Germans within the Austrian Empire, printed membership stamps with the phrase Arbeit macht frei. The phrase is also evocative of the medieval German principle of Stadtluft macht frei ("urban air makes you free"), according to which serfs were liberated after being a city resident for one year and one day.

Camp Construction and Expansion

The number of prisoners in the Flossenbürg concentration camp continued to rise. The arrival of new categories of prisoners fundamentally altered the composition of the prisoners’ forced community. Two years after the camp’s founding, the main buildings of the camp were all complete. An SS company, the German Earth and Stone Works (DESt), mercilessly exploited the prisoners to excavate granite. Over 300 inmates had already perished since the founding of the camp.

The first inmates of the camp were Germans, victims of the arrests of so called “criminals” and “antisocials.” In late 1938, the first political prisoners arrived. After the start of the war, Flossenbürg housed prisoners from across occupied Europe. The first Jewish prisoners arrived at the camp in 1940. By this time the first phase of camp construction had been largely completed and the quarry was in full operation. The camp housed over 2,600 prisoners, and the death rate began to rise. To dispose of the bodies of the dead, the SS ordered the construction of a crematorium in the camp.

Survival and Death in the Camp

Daily life in the concentration camp was dangerous and often deadly for the prisoners. Conditions were cruel and inhumane. Subjugated, humiliated, and exploited as forced labor, many prisoners died from mistreatment. The SS established a system of violence and terror in the camp and attempted to exploit the political, national, social and cultural differences among prisoners. Between 1938 and 1945, approximately 84.000 men and 16.000 women from over thirty countries were imprisoned in the Flossenbürg camp and its subcamps. All inmates were forced to wear prisoners’ garb bearing a number and colored triangle.

Living conditions deteriorated drastically over the course of the war. There was a steady rise in the number of accidents, illnesses and deaths. The ability to work increasingly determined a prisoner’s chance of survival. In late 1943, large transports began to arrive at Flossenbürg, overcrowding the main camp. Many prisoners were subsequently transported to subcamps. For most inmates, the decisive question became “How will I survive one more day?”

The Quarry

Thousands of concentration camp inmates were forced to work in the quarry, owned by the German Earth and Stone Works (DESt). Badly clothed and lacking all safety precautions, the prisoners were forced, no matter the weather, to remove soil, blast granite blocks, push trolley wagons, and haul rocks. Accidents were daily and routine. Backbreaking labor, freezing cold, severe malnourishment, and random SS and Kapo violence led to the death of many prisoners.

A work day in the quarry lasted twelve hours, interrupted only by a single break when a thin soup was served. The SS forced prisoners to walk in circles for hours, hauling rocks. Only a few prisoners survived these penal detachments. At the end of the work day, the prisoners carried the bodies of the dead back to the camp.

The camp quarry was the largest industrial operation at Flossenbürg. By mid 1939, approximately 850 camp inmates labored in the quarry daily; by 1942, the number had increased to nearly 2.000. DESt employed up to 60 civilian staff, administrators, stoneworkers, drivers and apprentices. Many of them had regular contact with the inmates.

SS rule in Flossenbürg

The administration and surveillance of concentration camps was one of the central duties of the SS (Schutzstaffel). SS members employed in the camps were all members of the Death’s Head Divisions (Totenkopfverbände). The SS conceived of itself as an ideological order and racial elite. Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer and head of the SS, developed the SS into a complex organization, involved in matters ranging from settlement policies to “combating enemies” and systematically killing members of so-called “inferior races.” In addition, the SS ran its own business enterprises.

In the concentration camps, the Death’s Head Divisions were organized into the command staff and the guard units. Each camp was headed by a Kommandant. Along with his subordinate departments, the Kommandant determined the prisoners’ fates. The SS staff were responsible for guarding the prisoners.

Approximately ninety SS members worked in the command staff at Flossenbürg. By spring 1940, the guard units had grown to a force of nearly 300. By 1945, with the construction of subcamps, the guard units expanded to approximately 2.500 men and 500 women. After the start of the war, many younger SS men were sent to the front. The SS leadership then engaged older men, air force soldiers, women, and foreign nationals for duty in the camps. After the war, the majority of SS members received only light punishment for the crimes they committed at Flossenbürg.

Death marches and liberation

The termination of the Flossenbürg concentration camp and subcamps began in early April 1945. Shortly before the end of the war, the prisoners the Germans deemed "fit to work elsewhere" where forced to evacuate to other camps in Germany. Thousands of prisoners died of exhaustion on the death marches, or were shot or beaten to death.

At approximately 10:30 hours on April 23, 1945, the first U.S. troops of the 90th Infantry Division arrived at Flossenburg KZ. They were horrified at the sight of some 2.000 weak and extremely ill prisoners remaining in the camp and of the SS still forcibly evacuating those fit to endure the trek south. Before the SS evacuated the camp, it erased the traces of its murderous activities and forced some 14.000 inmates to march southward. The 90th Infantry Division discovered around 5.000 bodies of inmates, who had died from exhaustion or starvation or had been killed by the SS guards because they failed to keep up with the pace of the march. When the 90th Infantry Division troops spotted the columns of prisoners and their SS guards, the guards panicked and opened fire on many of the prisoners, killing about 200, in a desperate attempt to effect a human shield and road blocks of human bodies. The 90th Infantry Division and the 97th Infantry Division found some 6.000 of these prisoners alive. American tanks opened fire on the Germans as they fled into the woods, reportedly killing over 100 SS troops.

Additionally, elements of the 97th Infantry Division participated in the liberation. As the 97th prepared to enter Czechoslovakia, Flossenburg concentration camp was discovered in the division's sector of the Bavarian Forest. Brigadier General Milton B. Halsey, the commanding general of the 97th Division, inspected the camp on April 30, as did his divisional artillery commander, Brigadier General Sherman V. Hasbrouck. Hasbrouck, who spoke fluent German, directed a local German official to have all able-bodied German men and boys from that area help bury the dead. The 97th Division performed many duties at the camp upon its liberation. They assisted the sick and dying, buried the dead, interviewed former prisoners and helped gather evidence against former camp officers and guards for the upcoming war crimes trials.

One eyewitness U.S. Soldier, Sgt. Harold C. Brandt, a veteran of the 11th Armored Division, who was on hand for the liberation of not just one but three of the camps, Flossenburg, Mauthausen, and Gusen, when queried many years after the war on his part in liberating them, stated that:

"It was just as bad or worse than depicted in the movies and stories about the Holocaust. . . . I can not describe it adequately. It was sickening. How can other men treat other men like this'"

OpenStreetMap service required

to load this map.

OpenStreetMap service required

to load this map.

Also known as:

Arbeit macht frei

3 May 1938 - 23 April 1945

Number of prisoners: 95.000 prisoners (of whom 16.000 female)

Prisoners murdered: 30.000

Original video footage

Real eyewitness testimony

Julian Noga

"A warm thank you to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum for their willingness to help in allowing their testimonies to be featured on my website.