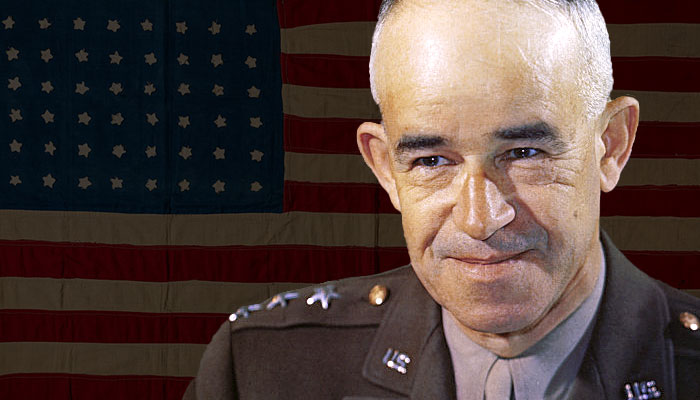

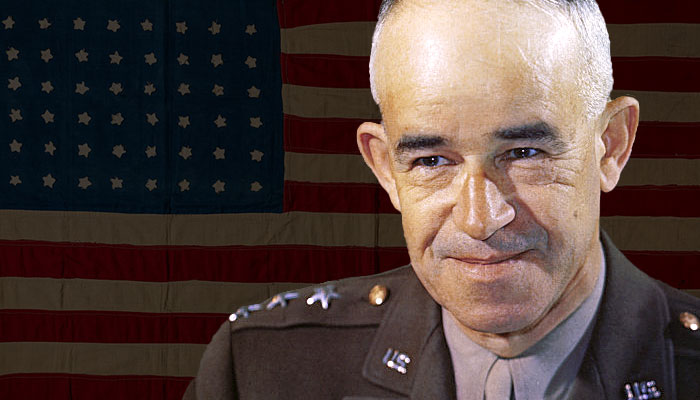

Life and death of Omar Nelson Bradley

Life and death of Omar Nelson Bradley, the facts

Omar Nelson Bradley (February 12, 1893 - April 8, 1981) was a United States Army field commander in North Africa and Europe during World War II, and a General of the Army. From the Normandy landings through the end of the war in Europe, Bradley had command of all U.S. ground forces invading Germany from the west; he ultimately commanded forty-three divisions and 1.3 million men, the largest body of American soldiers ever to serve under a U.S. field commander. After the war, Bradley headed the Veterans Administration and became Chief of Staff of the United States Army. In 1949, he was appointed the first Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the following year oversaw the policy-making for the Korean War, before retiring from active service in 1953.

Bradley's personal experiences in the war are documented in his award winning book A Soldier's Story published by Henry Holt & Co. in 1951. It was later re-released by The Modern Library in 1999. The book is based on an extensive diary maintained by his aide de camp, Chester B. Hansen, who ghost wrote the book using that diary. Hansen's diary is maintained by the U. S. Army Heritage and Education Center, Carlisle Barracks, PA.

Bradley did not receive a front-line command until early 1943, after Operation Torch. He had been given VIII Corps, but instead was sent to North Africa to be Eisenhower's front-line troubleshooter. At Bradley's suggestion, II Corps, which had just suffered the devastating loss at the Kasserine Pass, was overhauled from top to bottom, and Eisenhower installed George S. Patton as corps commander. Patton requested Bradley as his deputy, but Bradley retained the right to represent Eisenhower as well.

For the front-line command, Bradley was promoted to temporary lieutenant general in March 1943 and succeeded Patton as head of II Corps in April, directed it in the final Tunisian battles of April and May. Bradley continued to command the Second Corps in the invasion of Sicily.

Normandy 1944

Bradley moved to London as commander in chief of the American ground forces preparing to invade France in 1944. For D-Day, Bradley was chosen to command the US First Army, which alongside the British Second Army made up General Montgomery's 21st Army Group.

On June 10, General Bradley and his staff debarked to establish a headquarters ashore. During Operation Overlord, he commanded three corps directed at the two American invasion targets, Utah Beach and Omaha Beach. Later in July, he planned Operation Cobra, the beginning of the breakout from the Normandy beachhead. Operation Cobra called for the use of strategic bombers using huge bomb loads to attack German defensive lines. After several postponements due to weather, the operation began on July 25, 1944 with a short, very intensive bombardment with lighter explosives, designed so as not to create greater rubble and craters that would slow Allied progress. Bradley was horrified when 77 planes bombed short and dropped bombs on their own troops, including General Lesley J. McNair:

"The ground belched, shook and spewed dirt to the sky. Scores of our troops were hit, their bodies flung from slit trenches. Doughboys were dazed and frightened....A bomb landed squarely on McNair in a slit trench and threw his body sixty feet and mangled it beyond recognition except for the three stars on his collar."

However, the bombing was successful in knocking out the German communication system, leading to their confusion and ineffectiveness, and opened the way for the ground offensive by attacking infantry. Bradley sent in three infantry divisions—the 9th, 4th and 30th—to move in close behind the bombing. The infantry succeeded in cracking the German defenses, opening the way for advances by armored forces commanded by General Patton to sweep around the German lines.

As the build-up continued in Normandy, the 3rd Army was formed under Patton, Bradley's former commander, while General Hodges succeeded Bradley in command of the 1st Army; together, they made up Bradley's new command, the 12th Army Group. By August, the 12th Army Group had swollen to over 900,000 men and ultimately consisted of four field armies. It was the largest group of American soldiers to ever serve under one field commander.

Falaise Pocket

Hitler's refusal to allow his army to flee the rapidly advancing Allied pincer movement created an opportunity to trap an entire German Army Group in northern France. After the German attempt to split the US armies at Mortain (Operation Lüttich), Bradley's Army Group and XV Corps became the southern pincer in forming the Falaise Pocket, trapping the German Seventh Army and Fifth Panzer Army in Normandy. The northern pincer was formed of Canadian forces, part of British General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery's 21 Army Group. On August 13, 1944, concerned that American troops would clash with Canadian forces advancing from the north-west, Bradley overrode Patton's orders for a further push north towards Falaise, while ordering XV Corps to 'concentrate for operations in another direction'.[11] Any American troops in the vicinity of Argentan were ordered to be withdrawn. This order effectively halted the southern pincer movement of General Haislip's XV Corps.

Though General Patton protested the order, he obeyed it, leaving an exit—a 'trap with a gap'—for the remaining German forces. Around 20-50,000 German troops (leaving almost all of their heavy material) escaped through the gap, avoiding encirclement and almost certain destruction.[13] They would later be reorganized and rearmed in time to slow the Allied advance into Holland and Germany.[13] Most of the blame for this outcome has been placed on Bradley. Bradley had incorrectly assumed, based on Ultra decoding transcripts, that most of the Germans had already escaped encirclement, and he feared a German counterattack as well as possible friendly fire casualties. Though admitting a mistake had been made, Bradley placed the blame on General Montgomery for moving the Commonwealth troops too slowly, though the latter were in direct contact with a large number of SS Panzer, Fallschirmjaeger, and other elite German forces.

Germany

The American forces reached the 'Siegfried Line' or 'Westwall' in late September. The success of the advance had taken the Allied high command by surprise. They had expected the German Wehrmacht to make stands on the natural defensive lines provided by the French rivers, and had not prepared the logistics for the much deeper advance of the Allied armies, so fuel ran short.

Eisenhower faced a decision on strategy. Bradley favored an advance into the Saarland, or possibly a two-thrust assault on both the Saarland and the Ruhr Area. Montgomery argued for a narrow thrust across the Lower Rhine, preferably with all Allied ground forces under his personal command as they had been in the early months of the Normandy campaign, into the open country beyond and then to the northern flank into the Ruhr, thus avoiding the Siegfried Line. Although Montgomery was not permitted to launch an offensive on the scale he had wanted, George Marshall and Hap Arnold were eager to use the First Allied Airborne Army to cross the Rhine, so Eisenhower agreed to Operation Market-Garden. Bradley opposed Operation Market Garden, and bitterly protested to Eisenhower the priority of supplies given to Montgomery, but Eisenhower, mindful of British public opinion regarding damage from V-1 missile launches in the north, refused to make any changes.

Bradley's Army Group now covered a very wide front in hilly country, from the Netherlands to Lorraine. Despite having the largest concentration of Allied army forces, Bradley faced difficulties in prosecuting a successful broad-front offensive in difficult country with a skilled enemy. General Bradley and his First Army commander, General Courtney Hodges eventually decided to attack through a corridor known as the Aachen Gap towards the German township of Schmidt. The only nearby military objectives were the Roer River flood control dams, but these were not mentioned in contemporary plans and documents. Bradley and Hodges' original objective may have been to outflank German forces and prevent them from reinforcing their units further north in the Battle of Aachen. After the war, Bradley would cite the Roer dams as the objective. Since the Germans held the dams, they could also unleash millions of gallons of water into the path of advance. The campaign's confused objectives, combined with poor intelligence resulted in the costly series of battles known as the Battle of Hurtgen Forest, which cost some 33,000 American casualties.

At the end of the fighting in the Hurtgen, German forces remained in control of the Roer dams in what has been described as "the most ineptly fought series of battles of the war in the west." Further south, Patton's Third Army, which had been advancing with great speed, was faced with last priority (behind the U.S. First and Ninth Armies) for supplies, gasoline and ammunition. As a result, the Third Army lost momentum as German resistance stiffened around the extensive defenses surrounding the city of Metz. While Bradley focused on these two campaigns, the Germans were in the process of assembling troops and materiel for a surprise winter offensive.

Battle of the Bulge

Bradley's command took the initial brunt of what would become the Battle of the Bulge. For logistical and command reasons, General Eisenhower decided to place Bradley's 1st and Ninth Armies under the temporary command of Field Marshal Montgomery's 21st Army Group on the northern flank of the Bulge. Bradley was incensed, and began shouting at Eisenhower: "By God, Ike, I cannot be responsible to the American people if you do this. I resign." Eisenhower turned red, took a breath and replied evenly "Brad, I—not you—am responsible to the American people. Your resignation therefore means absolutely nothing." Bradley paused, made one more protest, then fell silent as Eisenhower concluded "Well, Brad, those are my orders." At least one historian has attributed Eisenhower's support for Bradley's subsequent promotion to (temporary) four-star general (March, 1945, not made permanent until January, 1949) to, in part, a desire to compensate him for the way in which he had been sidelined during the Battle of the Bulge. Others point out that both Secretary of War Stimson and General Eisenhower had desired to reward General Patton with a fourth star for his string of accomplishments in 1944, but that Eisenhower could not promote Patton over Bradley, Devers, and other senior commanders without upsetting the chain of command (as Bradley commanded these people in the theater).

Victory

Bradley used the advantage gained in March 1945—after Eisenhower authorized a difficult but successful Allied offensive (Operation Veritable and Operation Grenade) in February 1945—to break the German defenses and cross the Rhine into the industrial heartland of the Ruhr. Aggressive pursuit of the disintegrating German troops by the Ninth Armored Division resulted in the capture of a bridge across the Rhine River at Remagen. Bradley quickly exploited the crossing, forming the southern arm of an enormous pincer movement encircling the German forces in the Ruhr from the north and south. Over 300,000 prisoners were taken. American forces then met up with the Soviet forces near the Elbe River in mid-April. By V-E Day, the 12th Army Group was a force of four armies (1st, 3rd, 9th, and 15th) that numbered over 1.3 million men.

Death

Omar Bradley died on April 8, 1981 in New York City of a cardiac arrhythmia, a few minutes after receiving an award from the National Institute of Social Sciences. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery, next to his two wives.

-

Born: February 12, 1893

-

Clark, Missouri, U.S.A.

-

Died: April 8, 1981 (aged 88)

-

New York City, U.S.A.