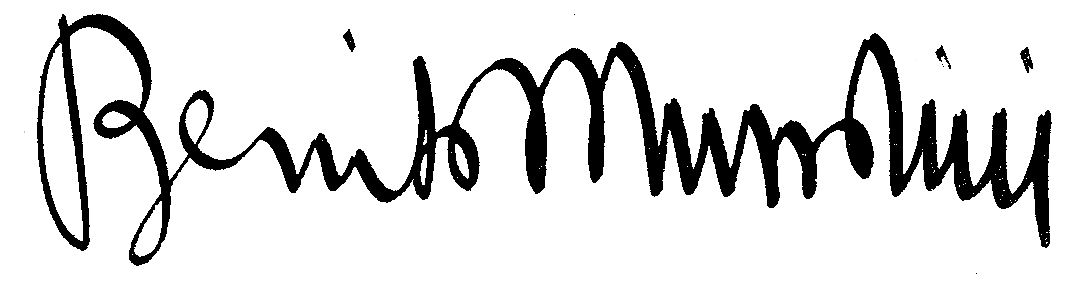

Life and death of Benito Mussolini

Life and death of Benito Mussolini, the facts

Benito Mussolini was born in 1883 in Predappio, Italy, into a socialist family. He began his political career as a journalist and editor for the socialist newspaper Avanti!, advocating socialist ideas and Italian intervention in World War I. His support for Italy joining the war led to his expulsion from the Socialist Party. In 1919, he founded the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento, a nationalist and revolutionary movement that later evolved into the National Fascist Party (PNF). Mussolini’s charisma, dynamic rhetoric, and promises of national rejuvenation resonated with Italians frustrated by postwar instability, economic hardship, and political unrest.

In 1922, exploiting the widespread chaos and weakness of the liberal government, Mussolini led the March on Rome, compelling King Victor Emmanuel III to appoint him Prime Minister. Over the next decade, Mussolini systematically dismantled democratic institutions, suppressed political opposition, and established a totalitarian regime. Under his rule, the state controlled the economy, media, and education while promoting militarism, nationalism, and the concept of a corporatist state. Fascist propaganda emphasized loyalty to the nation and the Duce, while the regime sought to instill discipline and unity among Italians, including youth movements and paramilitary organizations.

Foreign policy and pre-war expansion

By the late 1930s, Mussolini believed Italy and Germany were destined to dominate Europe due to their “virile” populations, while Britain and France were declining powers. He often referred to France as “weak and old” and predicted the decline of the British Empire, influenced by demographic trends and low birth rates. Mussolini’s approach to international relations reflected a Social Darwinist worldview, seeing the global stage as a struggle between strong and weak nations.

Despite his ambitions, Mussolini initially hesitated to fully commit Italy to war with the Western Allies. The Italian economy and military were unprepared for large-scale conflict, and Mussolini attempted to use the Easter Accords of 1938, an Anglo-Italian initiative, to drive a wedge between Britain and France. He envisioned Italy confronting France alone to expand its influence in Tunisia and the Mediterranean while maintaining cordial relations with Britain to secure neutrality. Mussolini’s expansionist goals focused on Tunisia, Djibouti, and Corsica, while he showed little interest in annexing Savoy. Demonstrations in Italy in late 1938 raised tensions with France and demonstrated Mussolini’s willingness to use public pressure to advance his ambitions.

By early 1939, Mussolini’s foreign policy shifted decisively toward Germany after realizing Britain would not abandon France. In April 1939, he ordered the invasion of Albania, quickly occupying the country and forcing King Zog I into exile. In May 1939, Italy formalized its alignment with Germany through the Pact of Steel, pledging mutual military support while still cautiously avoiding immediate war. When World War II began with Germany’s invasion of Poland in September 1939, Italy initially remained neutral, reflecting Mussolini’s awareness of Italy’s unpreparedness and King Victor Emmanuel III’s insistence on neutrality. Mussolini occasionally acted independently, such as intervening to secure the release of 101 Polish academics arrested in Kraków in November 1939, demonstrating his personal influence on foreign affairs despite strategic caution.

World War II and Military Campaigns

As World War II unfolded, Mussolini remained cautious, balancing opportunities for expansion with Italy’s military limitations. While Britain sought Italian support against Germany, and France considered a strike in Libya, Mussolini delayed full engagement, partly due to warnings from his Under-Secretary for War Production, Carlo Favagrossa, who estimated Italy’s industrial base could not sustain large-scale operations until at least 1942.

By mid-1940, with Germany achieving rapid victories in Western Europe, Mussolini committed Italy to the war. On 10 June 1940, he declared war on France and Britain from the balcony of the Palazzo Venezia in Rome, urging Italians to demonstrate courage and valor. Italy’s entry was rushed and poorly planned, lacking a coordinated military strategy. Italian forces immediately participated in the Battle of France, launching the Italian invasion across the Franco-Italian border. Following France’s armistice with Germany on 22 June 1940, Italy signed the Franco-Italian Armistice on 24 June, gaining control over southeastern territories, including most of Nice.

Mussolini then turned his focus to the British Empire in Africa and the Middle East, a campaign he described as a “parallel war.” Italian forces invaded Egypt, bombed Mandatory Palestine, and advanced in Sudan, Kenya, and British Somaliland, capturing the latter on 3 August 1940. Despite initial successes, these campaigns faltered, and Britain rejected any peace settlement recognizing Axis territorial gains. Mussolini framed Italy’s involvement as an ideological struggle, portraying fascism as the force of youthful vigor against the “plutocratic and reactionary democracies of the West,” reflecting his belief in the existential stakes of Italy’s engagement.

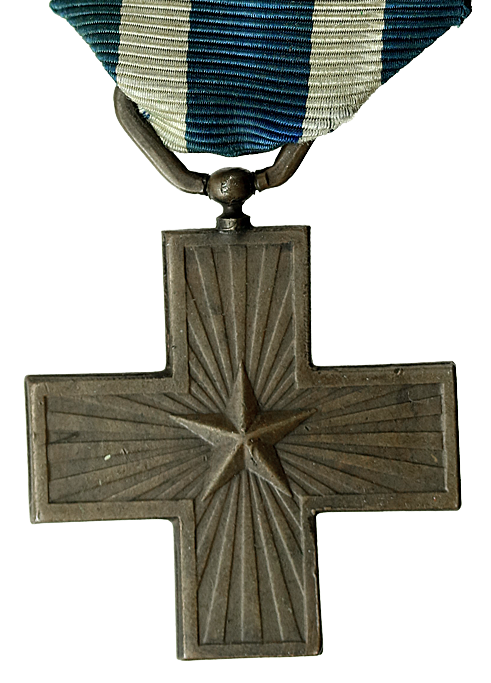

As commander of Italy’s armed forces, Mussolini oversaw campaigns that were often overambitious and strategically flawed. In September 1940, under Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, the Italian Tenth Army invaded Egypt from Libya, marking the start of the Western Desert Campaign. Initial advances stalled at Sidi Barrani due to logistical difficulties. Meanwhile, Italian campaigns in Greece and the Balkans faced strong resistance, leading to stalemates and reliance on German assistance. By early 1941, British forces had pushed Italian troops back in North Africa during Operation Compass, while Italian East African forces were defeated at Keren and Gondar. Italian forces annexed some territories in Yugoslavia and Greece while suppressing partisan uprisings, extending Italy’s regional influence.

Italy later contributed troops to Operation Barbarossa on the Eastern Front at Hitler’s request, suffering heavy losses and eroding public support. Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Italy declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941, formally aligning with the Axis. Italian forces achieved limited successes alongside German allies in North Africa, notably at Gazala, but were decisively defeated at the Second Battle of El Alamein in late 1942. Allied advances continued, resulting in the loss of Libya by January 1943. Italy occupied Corsica and Tunisia following the collapse of Vichy France, using Tunisia as a base during the Tunisian Campaign. Despite overextended resources and repeated setbacks, Mussolini remained committed to sustaining the war in an effort to preserve Italy’s territorial ambitions.

Decline and dismissal

By 1943, the situation had become dire. Axis forces were defeated in North Africa, Sicily was under Allied invasion, and Italian troops struggled on the Eastern Front. On the home front, shortages of food and raw materials caused unrest, industrial strikes erupted, and public confidence in Mussolini collapsed. On 24 July 1943, the Grand Council of Fascism voted against him, giving King Victor Emmanuel III the authority to remove Mussolini from power. The following day, the king dismissed Mussolini and placed him under arrest. Marshal Pietro Badoglio became prime minister, dissolved the Fascist Party, and secretly began negotiations with the Allies.

Italian Social Republic (RSI)

Mussolini was freed on 12 September 1943 during the daring Gran Sasso raid, carried out by German Fallschirmjäger and Waffen-SS commandos under Major Otto-Harald Mors and overseen by Otto Skorzeny. Three days later, he met Hitler in East Prussia and agreed to establish the Italian Social Republic (RSI), headquartered in Salò on Lake Garda. Declared on 23 September 1943, the RSI was a German puppet regime controlling only the German-occupied regions of northern and central Italy.

Mussolini’s authority was limited. Key border regions, including the Alpine Foothills (Bolzano, Belluno, Trento) and the Adriatic Littoral (Trieste, Fiume/Rijeka, Ljubljana), were directly administered by Germany. He lived under SS supervision in Gargnano and presided over a collapsing regime marked by internal purges and German dominance. Under Nazi pressure, Mussolini approved the execution of former fascist leaders, including his son-in-law Galeazzo Ciano, while attempting to maintain Italy’s war effort. In his final months, Mussolini appeared increasingly disillusioned, describing himself as “little more than a corpse.”

Death

As Allied forces advanced through northern Italy in April 1945, Mussolini and his mistress Clara Petacci attempted to flee to Switzerland on 25 April. Their convoy was intercepted by Italian partisans near the village of Dongo on Lake Como on 27 April. Mussolini and Petacci were executed by firing squad on 28 April 1945 in Giulino di Mezzegra. Their bodies were publicly displayed in Milan’s Piazzale Loreto, a symbolic act of retribution for Fascist atrocities, hung upside down for public viewing.

Legacy

Mussolini’s death marked the definitive end of Fascist rule in Italy. His career illustrates the rise and collapse of authoritarian regimes, the consequences of overambitious military campaigns, and the human cost of totalitarian governance. The Italian Social Republic serves as a historical example of a puppet state under German occupation, while Mussolini’s life underscores the dangers of ideological extremism combined with unchecked political and military ambition.

-

Born: 29 July, 1883

-

Predappio, Italy

-

Died: 28 April, 1945

-

Giulino di Mezzegra, Italy